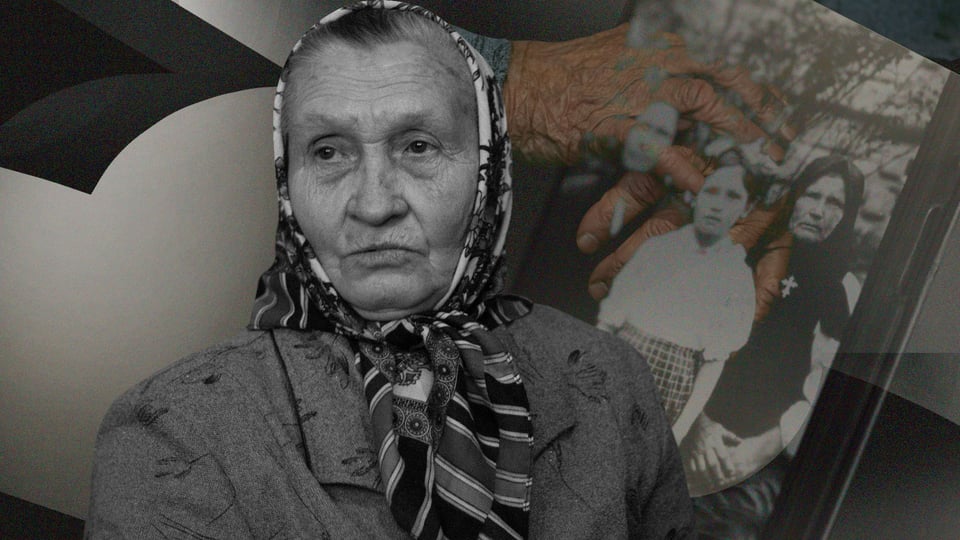

“I was born during the war, and I may have to die during the war, too”

The fate of 79-year-old Halyna Rozhok from the Chernihiv region epitomizes the life of many village women born during or after World War II. Hunger, poverty, hard daily labor, and the inability to leave the village. Nevertheless, she overcame these challenges with song and wisdom, growing bread and raising her children.

We meet Ms. Halyna in the village of Koniatyn, 115 kilometers from Chernihiv. This is where she has lived all her life, raised five children, and saw her nine grandchildren and three great-grandchildren to be born.

In a snowy village yard, we are greeted by cats and a small dog brought home by her granddaughter Polina. Today, Halyna Rozhok lives with her daughter Vira, whose husband and son are at war. Since 2014, six members of the family have been at war, and some are still fighting for independence.

“It seems like life is better now, my daughter took me, she takes good care of me, but the war started. I was born during the war, and I may have to die during the war,” Halyna says during the meeting.

Burned house and post-war famine

Halyna's mother, Paraska Synihovets, was widowed twice because of the war. Her first husband was taken prisoner. The woman went to a camp in the Kharkiv region to rescue him, hoping that the Germans would take food and release her husband, but she found out that he had already been shot.

Later, during the Soviet army's offensive and the liberation of the village, Paraska met a soldier, Ivan. But рe did not return from the war as he was also killed. In 1944, she gave birth to a daughter, Halyna.

Halyna Rozhok recalls that their house burned down during the liberation of the village from the Nazis. In order to have a place to live, they built a barn with two windows next to the ashes, which their mother bought from a wealthy man. The three of them lived there: little Halia, her mother, and grandmother Onysia.

The girl's biggest dream was to have her own home, but the path to it took more than a decade. Only in 1962 did the family manage to build a new house.

Halyna recalls the famine of 1946-1947 with tears in her eyes. Despite her early age, she remembers going to the field with her grandmother to collect ears of grain in a small bag. Then a ranger caught them and took them to the collective farm barn, where he forced them to throw everything they had collected into a common pile.

The woman says that the family has always kept a cow and chickens, which is why they managed to survive. There was milk, cottage cheese, and eggs. Of course, adults fed the child first.

Halyna's mother worked hard at the collective farm, because in the postwar period there were few men in the village. So most of the work was done by women. They didn't receive any money for their work, only labor days.

In order to have some money in the household, she would go to the market almost every Sunday in the nearest towns or villages and sell some food or brushes to paint the houses.

In the postwar period, high taxes were added to all sorts of domestic difficulties in the village: villagers had to pay the state for almost every tree in their garden and chicken in their yard. In addition, they had to buy government bonds. No one asked whether you could, you had to buy them.

There were also meat harvesting quotas: no one cared if you had few livestock or a large family, you had to meet the quota. It was impossible to apply for firewood, but the house was heated by a furnace, so people made arrangements illegally. One day, a man brought logs to the yard, and when the forester saw them, he fined not the man who brought them, but those who ordered them.

Halyna recalls going caroling as a child. Traditionally, her godmother would come to visit her and bring her gifts. They would put a pine tree in the house and decorate it with homemade snowflakes and candy wrappers.

At Christmas, they made kutia, to which they added crushed poppy seeds. In addition, the villagers made pies with a sweet filling of beans (boiled and ground) and poppy seeds. There was no way to buy sugar, but the villagers grew sugar beets, so they boiled them and used the water to make a compote.

“When I was a child, it was a church, and when I was a young girl, it was a club.”

In 1958, Halyna graduated from a local school. Her mother, probably dreaming of an easier life for her daughter, wanted to send her to study to become a beekeeper. But it didn't work out. It was very difficult for young people to leave the village back then. It was a kind of legalized form of slavery: Soviet villagers did not have passports for a long time, and therefore were deprived of their rights.

And Halyna was eager to go to work to rebuild the house as quickly as possible. She has 38 years of experience in agriculture. She has worked as a link worker and on a pig farm.

“In my first year of working at the collective farm, I earned 400 labor days. I pulled haystacks, plowed the field with horses, and did other work that is considered a man's job,” thewoman says.

She recalls that in her youth, young people in the village used to go to parties in the fall and winter, and in the spring and summer they would relax outside. The village of Koniatyn is located on the Desna River, so when the floods began in the spring, young people would go boating and sing in the evenings after work.

It's evening, everything is in bloom, and singing is coming from different directions — this is how many villagers remember spring evenings. And Halyna as well. Back then, there were many girls and many boys in the village, and songs were heard everywhere. At that time, the village club was set up in a former church building.

“When I was a child, I remember going to church with my grandmother, and when I was a young girl, we went to a club,” recalls a resident of Koniatyn.

And then the building was dismantled, and the wood from the former church (which was especially strong due to the special processing technique), even with some wooden icons, was taken to the cowshed and pigsty for heating. This is how the government of the godless people acted, the woman says.

At the age of 24, Halyna married a local boy, Anatolii Rozhok. At the village wedding, as was customary at the time, the bride and groom wore Ukrainian national clothes. The bride wore a vyshyvanka, plakhta, skirt, and a wreath with ribbons on her head.

“I grew up alone, so I wanted my children to have brothers and sisters,” she says.

The couple had three sons, Serhii, Mykola, and Viktor, and two daughters, Valentyna and Vira. Halyna divorced her husband when her youngest son was born.

Anatolii went to live with his parents, although he kept in touch with the children. But his mother had to take care of them more. In addition to her children, Halyna also raised her grandson Vadym, as she became his guardian from the age of 6.

According to her daughter Vira, her mother raised them all with the understanding that brothers and sisters are the closest people, so they should always support and help each other.

The second war came to the family in 2015

Viktor, Halyna's youngest son became the first participant in the hostilities. In 2015, he was mobilized as an instructor to prepare soldiers for a military unit in the village of Desna. But eventually he found himself at the front — near Debaltseve. After fighting for a year, Viktor was demobilized and now works in a forestry enterprise.

Halyna's son-in-law, 48-year-old Mykola Komar, also went through the crucible of the war in Donbas, served for 14 months and was demobilized. Upon returning home, the man told his family that Russia's invasion of Ukraine would not end with Donbas. The war will come to other territories as well. But his words were not taken into account at the time.

With the beginning of the full-scale invasion, three men from the family were mobilized into the Armed Forces: son-in-law Mykola, son Mykola, 52, and grandson Vadym, 30.

Another grandson, Illia, and his wife Maryna, were contract soldiers in Odesa at the time of the full-scale invasion. Illia enlisted in the Navy at the age of 20, then signed a contract and fought in the Donetsk region. Now 26, Illia continues his service, defending the country, and his wife is taking care of their young daughter.

According to Halyna, her grandson Vadym was seriously wounded in August last year. During the explosion, he was covered with earth, and only his brothers-in-arms who returned to their positions to take radio found and rescued him. The man suffered a leg injury and was treated in several hospitals. Vadym is still undergoing rehabilitation.

Given her advanced age, Halyna Ivanovna is more involved in household chores. She worries about her grandson, son and son-in-law who are at war. She is waiting for her granddaughter Polina to come home from Chernihiv for the holidays.

So, on the eve of the New Year holidays, Halyna dreams of gathering her whole family together after the victory — her children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren — and having everyone alive.

This text is part of the Children of War special project, in which we tell the stories of Ukrainians who witnessed the Second World War or its aftermath as children and are now experiencing another tragedy in their old age.

The publication was created as part of a project funded by the German Foreign Office to support Ukrainian independent journalism.

Author: Iryna Synelnyk