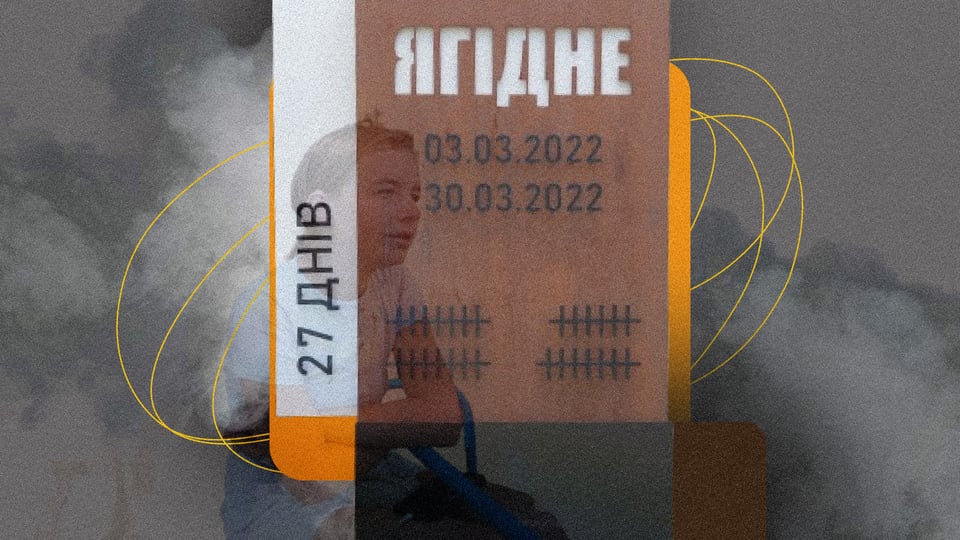

What do you do with memories of 27 days on the brink of life and death? Report from Yahidne

Over two years ago, the village of five streets next to the highway was almost destroyed by the Russians. But the worst thing that happened to the people of Yahidne in the Chernihiv region wasn't this. It was being held in a Russian concentration camp for a month. More than 300 people were held in the basement of a local school by the occupiers.

Maryna Suprun was in tenth grade at the time and managed to survive captivity with her family. To work through her pain and find ways to overcome it, she wrote down her memories for the therapeutic book Living Against All Odds: Women's Stories of War, 2014 and 2022. Together with Maryna, who is now a student at a university in Kyiv, we took a stroll through the streets of her hometown. A village that has lost its peace and quiet…

Should we share our grief and... berries?

There is now a checkpoint with protective structures near Yahidne. “Let it be,” the locals say, as if checking off at least one reason to feel safe. But it seems that this sense of security and carefree feeling has not yet been revived: people say that if the occupiers attack again, they will definitely not forgive Yahidne for what it has witnessed and testified to. Crimes and the true face of the “Russian world”

The village, whose fences are full of signs of foundations and benefactors who have restored the “boxes” of houses, is not very crowded. Houses with new roofs stare out of their empty windows without curtains. The inside of many of them is empty — repairs are still underway, traces of fires can be seen on the walls, and Russian hardware is rusting near the shot fences. And everywhere underfoot, the bounty of summer — cherry plums, plums, peaches, apricots, apples and pears — is rotting away.

“When I was a teenager, I used to sit with baskets of berries and fruit in the summer — almost everyone in the village had their own place along the highway. People would stop and buy, and it was great for them and us, of course, because it was my ‘pocket money’,” says Maryna, biting into an apple with a red side that had fallen into the grass, so it didn't get hit too much. “I joked a lot, was always positive, so people bought from me well. I remember my grandmother waving my ‘first profit’ at me to make money.”

Maryna laughs as she shows how a superstitious old woman “crossed” her with banknotes. And now, she says, there are no fruits or berries for sale on this road. They don't even pick them: “We can't share them, just like we can't share our grief, because it seems inappropriate.” The only thing they do is give the berries to wholesale buyers for a pittance, not worth the scratches left on their hands by the thorny bushes.

...I must say that I love flowers very much. I love them so much that the first thing I packed my herbarium into my emergency suitcase. These flowers are my memories. The book with the herbarium was too big to take away. So I quickly put everything in an envelope and hid the envelope with the herbarium in the pocket of my black jacket...

Maryna, giving a tour of the streets of her incredibly green and fragrant village, says: “You see, everything is being rebuilt. Our beautiful nature is being restored, the earth bears fruit, and the storks have come to build their nests. Some people may never come back here, but most of us will live here.”

“But it will probably be a different village. Not the one where I spent the best carefree years of my childhood. I want to remember it as such, but we need to do something with the memory of those 27 days that we all lived together on the brink of life and death. When older people were dying on the benches nearby, and adults were in pain because they couldn't protect their children,” the girl says as we approach the school, which is now unlikely to ever accept children inside its walls. “I can't speak for others, but I always have a plan in my head now how to save my family from here. There is a constant feeling of danger and anxiety. I don't know anything worse than what we had to go through.”

...That day, around noon, I heard a rumble from behind the forest. Tanks were driving. There was only one hope in my heart — they would pass on. I heard a machine gun burst, followed by many more. The fear of losing my beloved was the greatest. I would never want to feel that way. There was not enough food, no hot water and electricity. But it was not so important in comparison to this fear. They were laughing, shooting, running on the surface. And we were down there, saying goodbye to each other. They were Russian soldiers. Mom, me, and little Kristinka in a tight embrace, so tight that even tears as heavy as stones had nowhere to fall. We were waiting for death together. And only then did I realize that people were lying... Death has no scythe. She's carrying an assault rifle...

All conversations end with those memories

There are various support and assistance missions in the village — some of the teenagers have completed a whole course of psychotherapy in recreation and rehabilitation camps. Maryna was also in one of these — it helped her to speak out, work through her feelings of guilt, and face her fear. And writing an essay for the book made her feel that what she went through and the path to recovery was worth telling.

“You know, at first no one even wanted to talk about it. It seemed that the sooner we forget it, the easier it will be to live,” Maryna says next to the symbolic sign that was installed near the school basement. “Of course, when I meet new people, I don't start telling everyone about it right away. But it's not always possible to hide it either — no matter how hard you try, any conversation now ends with the topic of war. And for me, these are not even memories of the occupation, but of captivity — I believe that this is not the same thing.”

The experience of collective trauma, common to almost all members of the community, needs to be studied and responded to. And help is needed. Those who survived torture and those who were left in their homes by the occupiers for their loyalty must somehow live together. Those who risked their lives to help others, and those whose weaknesses were seen by the whole village. Those who “went with everyone” so that the nonhumans would not touch the girls, and those who now consider them whores...

“We tried to help people talk about how to remember it. But not only this crime against the villagers. People want to remember the village as it was in peaceful life. People want to remember those who resisted, even if it was only the slightest. Those who helped to find food despite the danger. People want to remember those who protected and defended them. And most of all, people want to live on. People do not want to turn their village into a solid granite monument. I really want to support them in this. And not only them. We have a lot of settlements that are going through a similar experience: how to remember and how to live on. And how to do it in a different way than the Soviet way,” wrote Iryna Eihelson, a candidate of psychological sciences, after visiting Yahidne.

When you walk the streets and talk to single people, you can't help but feel that the village is trying to fill this void — in the restored houses and in their own lives. Maryna enters the basement for the third time since her release, and says she feels almost nothing. She even seems a little proud that she can come back here without crying. It's like being inoculated with small doses of pain. And the girl believes that nothing should be changed in this basement — let people have the opportunity to look at it. No need for any museums or tours — just leave everything as it is. It speaks for itself about everything you need to know. She shows the place where she slept with her friends — at the bottom of a two-story structure that the men made from kindergarten cots. She wants to show something important, but the humidity and time have done their job — Maryna tries to find the inscription, but the letters are almost invisible. Time is taking its toll...

...We hummed songs, read to each other books that the scum had thrown out of the school library. Most importantly, on the bed above us, we wrote the poem “Kateryna” by Taras Shevchenko from memory. With a red felt-tip pen, as I remember now. These memories are with me to the end, or I am with them...

Should we sing on the ashes?

She has not yet decided what to do with these fears and hatred. She thinks that maybe she should go to war. But now Maryna is studying journalism and singing. We are standing near a destroyed building — this used to be the center of cultural life in Yahidne. The girl recalls this very warmly in her essay:

…The local House of Culture also burned down, I saw it. I saw my life burning. There were six girls in our singing group and one leader, Uncle Roma. We created, invented, never acted according to a template. The people of Yahidne, the residents of my village, were always waiting for our concerts. Our last peaceful performance was in February 2022, I think it was around the 12th. We were invited to perform at a birthday party at the local cafe “Romashka”. By the way, it also burned down…

Maryna shows the place where the stage used to be. She stands in front of it for a long time, and at some point it seems that the girl is about to start singing. But no — the only thing that breaks the silence is the sound of construction work that goes on throughout the village. We silently leave the ashes and sit down on a swing — after the liberation, a playground was built here, where children and teenagers now gather in the evenings to hang out. But during the day, it's empty — everyone is busy with their business.

Maryna recalls a lot about the first time her family returned to Yahidne after the evacuation. How she thought she would never be able to walk calmly through the streets where there was broken military equipment, how she was frightened of the death of her own house, which seemed to never be filled with life again. But suddenly, volunteers started coming to the village. Many different initiatives, interesting people with whom you want to be friends and do useful things together. A whole volunteer camp settled near the House of Culture: people set up tents, cleared the rubble, and repaired houses.

“And it was really cool! In the evenings, there were concerts right here, and you know, even the local pensioners didn't mind the noise and hype and parties like that. I sang too — yes, right here, on the ashes. Our people came to listen, they were very supportive. Well, they burned down the house, but I stayed alive for a reason, so I have to do what I can do!” says Maryna with emotional fervor.

She admits that the volunteers who came to Yahidne had a great impact on her outlook. She was amazed by the desire of other people to help, not to be afraid of difficulties, and to believe in the possibility of changing things for the better. From a schoolgirl who was just waiting for death a few months ago, praying only that she would not see her sister and mother die, she has turned into an active girl who consciously participates in socially important projects. On the advice of volunteers who became Maryna's friends, she starred in a documentary about Yahidne by a French director and even attended the presentation of this movie in Paris.

“This experience has changed us all. Our values above all. I'll never forget how I hugged my mother and sister when the invaders entered the village, and she told us: ‘If something happens to me, don't leave each other’,” says Maryna. “I hope I won't spend my whole life in memories. But I wouldn't want it to be forgotten either...”

We enter the local cemetery: there must be a place for the memory of tragedies so that pain and longing do not fill the entire space that is trying to become alive again. Here, in March 2022, the occupiers allowed the digging of a pit where the bodies of the killed and those who died in the school basement were dumped. After the de-occupation, the bodies were exhumed and the locals were buried. The graves are in different corners of the cemetery, but they can be distinguished by their common dates of death. There are very elderly women who died of suffocation and young men killed for disobedience. Here and there, flags fly — Yahidne has his own account of this war...

...My herbarium has long since turned to ashes. I had completely forgotten about it, but I didn't even think about scattering it to the wind...

Author: Lidiia Kvashchenko

Quotes are taken from the book “Living Against All Odds: Women's Stories of War, 2014 and 2022”, prepared by the Eastern Ukrainian Center for Civic Initiatives with the support of the Partnership for a Strong Ukraine Foundation.