One-way ticket: journalist's experience of being an IDP after Russia's invasion

In the spring of 2014, the Russian military invaded and seized the cities of Luhansk, Donetsk, and parts of these oblasts. Back then, nine years ago, hundreds of thousands of people left with the hope of returning home soon, but most of them have not yet done so. Families were divided, and children often could not bury their parents.

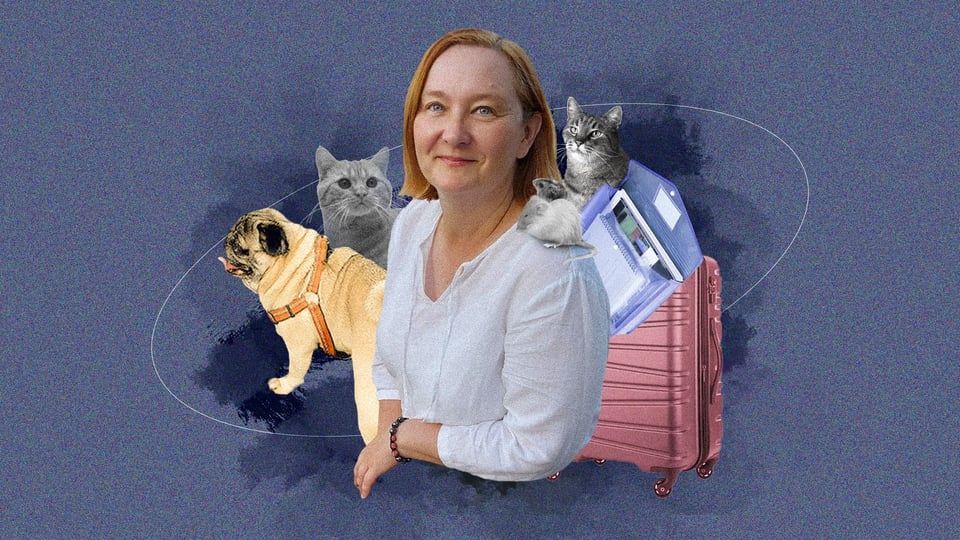

Journalist Natalia Adamovych left her native Sverdlovsk, now Dovzhansk, in 2014. In 2022, she was forced to become an IDP again and start her life from scratch abroad. Natalia told hromadske about her experience.

I have always loved March. This month is both my birthday and my mother's. "Russkiy Mir” (‘Russian world/peace’) took away this love on March 1, 2014.

I will never forget this date. On the first day of spring, in my small and comfortable city of Sverdlovsk in Luhansk Oblast, Russian flags flew in the central square and [Ramzan] Kadyrov's snipers appeared on the tall buildings.

But the realization that events were becoming irreversible came only in May, when armed men without insignia seized the border outpost. By the way, the main office of the border guards was located in the center of the city: between an apartment building, a kindergarten and the detached housing neighborhood. If our soldiers had launched an active defense, civilian casualties would have been unavoidable. However, the Ukrainian border guards had no chance. They were outnumbered by those who were besieging them, and the [invaders] had more weapons.

I was at work in the newspaper office when a friend called me: "They are going to block the border outpost". I dialed a military friend: "San, be ready". His response was: "Too late".

A day later, the Ukrainian military in Dovzhansk, then still Sverdlovsk, was gone. After they left, everything Ukrainian disappeared from the city. Instead of the yellow and blue flag, the flag of the city appeared on the flagpole of the city council building — not of the mythical "Novorossia" or "LPR". It was as if the city was waiting for this absurdity to end. But it turned out that it was only the beginning.

I was happy about one thing: In 2014, my daughter Regina graduated from high school and received a Ukrainian diploma as we just managed to do it. And we went with her to the city of Dnipro to take the External Independent Testing.

What did I think about on the train when I was leaving for the west to the cannonade of guns in Luhansk’s Kambrod district? Definitely not that this is a journey without a return. We even had a return ticket two weeks later. It's still in my old wallet, along with the keys to my apartment. I've tried to throw it away many times, but I can't. It seemed like it would finally kill the hope of getting home.

But then, in 2014, we did not know that trains would soon stop running in this direction. And there would be nowhere to go back to. There was hope that everything would soon be as it was before. So the journey did not seem burdensome. Thoughts about where to live in Dnipro were mixed with thoughts about the work that would have to be done after the return.

The first wake-up call that things are different now rang when the train passed Mezhova, a railway station on the border of Dnipropetrovsk and Donetsk oblasts. For the first time in months, I saw the Ukrainian flag. And I cried.

I said goodbye to Dnipro in 1995 when it was still Dnipropetrovsk. I graduated from the university there and did not think I would ever return. But in the spring of 2014, this city seemed like the best option because I knew it well. Or rather, I thought I did.

In fact, almost two decades later, everything was not as I had imagined. I remembered the city of the 1990s, quiet, calm, even indifferent. But I met a different Dnipro. Active, strong, lively, and truly Ukrainian. Blue and yellow flags in every house on the windows and balconies, and the Ukrainian language. And columns of our military equipment. I remember the video "Come Back Alive" about the Ukrainian Armed Forces was constantly broadcast on the big screen of the Dnipro Passage. I used to come there on purpose to watch it again.

But that was later, in 2015. A month after we had arrived, it became clear that we were here for a long time. So, I had to look for a job. I paid visits to editorial offices at the addresses that I found on the Internet. In the first one, I heard: "Leave your details" (between the lines meaning: we don't need employees). The second was the editorial office of the newspaper Nashe Misto. I worked there as a journalist from August 2014 to the fall of 2017.

For me, Dnipro is a city where people who are not indifferent to other people's grief live. When the flow of migrants from eastern Ukraine began, the citizens created the Dnipro Help Center. People could find shelter, food, clothing, and support there.

This city gave me the opportunity to meet volunteers who help the army. For four years, I visited Avdiyivka, Toretsk, Ocheretyne, Vodolazke, and other cities and towns that had already been fully affected by the war. Destroyed housing, broken windows, tracked vehicle marks on the asphalt, and fear in their eyes. And at the same time, the warriors, next to whom you feel confident, despite the sounds of cannonade. They gave you hope that everything would be okay, just like now.

Dnipro gave me the opportunity to believe in myself again. So much so that the unexpected move to Kyiv in 2017 no longer scared me.

I had already been to Kyiv 20 years ago. I love this city. My daughter was born there. Every time I returned from a business trip to the capital, I thought: "Why can't I stay here?" Be careful what you wish for. When Regina entered a university in Kyiv, it became clear that it would not be possible to split time between the two cities. We moved in three days.

"It's a blessing that we don't have any furniture," I thought at the time.

And it started all over again: looking for a job, housing. It was both easier and harder. This move was no longer perceived as a disaster. But I had no close friends here. I often recalled the phrase from Alice in Wonderland: "Here we must run as fast as we can, just to stay in place. And if you wish to go anywhere you must run twice as fast as that."

Living from scratch in my late 40s gave me confidence that there is no wrong age or time for a change. I thought: "I don't know where I will be tomorrow. But I will be nonetheless, and that's enough."

My mother came to Kyiv once. Then she kept promising to return... But she never got out of the occupied territories. I could not visit my parents, even when it was still possible to get to the occupied Donbas.

On February 21, 2022, I wrote on Facebook: "My daughter is sitting over the books, choosing what to take with her. This is the second library we have amassed. The first one was left at home in 2014. I don't have the strength to look at her doomed figure and realize that she will have to go through this journey a second time. To lose everything: your home, friends, the opportunity to see your family. I hate Russians."

On February 24, we woke up to explosions in Boryspil. Two cats, two rats in cages, a pug and a backpack with documents. The next stage of our life began there. Then came Poland, Germany, and now the UK.

Last year, my father died. I had not seen him since 2014. I have almost accepted that I would not see my mother either as she is over 80. It hurts. But it does not diminish my confidence that Donbas will be Ukrainian. Almost a decade of occupation should have radically changed the locals, it would seem, because of the powerful Russian propaganda and lack of information. But this is not the case. Many people there are waiting for the Ukrainian military.

Now Dovzhansk is in the deep rear near the border with Russia — it does not hear explosions, is not subject to shelling. When the occupiers are driven out, the war will spread there as well.

"It's scary, but we'll stay in the basements. And even if they kill us, it's okay, we've already lived. As long as it’s Ukraine," I heard recently.

I believe in my Ukrainian Donbas.

Author: Natalia Adamovych