The Three After Midnight Museum in the Dark: how visually impaired guides lead tours, make coffee, and break down stereotypes

When a person finds themselves in total darkness, the first thing they feel is stupor and confusion. Then, following prompts, they begin to master the situation, orienting themselves by touch, hearing, and smell. Everything here is unfamiliar. Ordinary places — a ‘street,’ an ‘apartment,’ a ‘park’ — become foreign and full of challenges. To navigate the route, one needs the advice of someone accustomed to living in the dark: a guide with vision impairments.

This is how tours unfold at the Three After Midnight Museum in the Dark, which not only offers visitors new impressions but also challenges stereotypes about people with visual impairments. Its name signifies three o'clock in the morning — the darkest time of day. Over eight years of operation, more than 85,000 people have attended tours at the Kyiv and Lviv branches. Meanwhile, the 03:00 Foundation, which emerged from the museum, works to expand inclusion in Ukrainian society and create new opportunities for people with vision impairments.

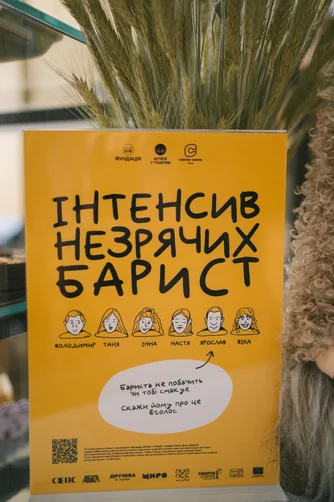

One of them was launched with the support of the House of Europe. Guides working at the museum were offered the opportunity to learn how to make coffee using professional equipment to master the profession of barista. In the future, the training and internship program will be available to other people with visual impairments.

Alina Marnenko, founder of the Museum in the Dark, told Hromadske how the project turned from a hobby into her life's work, why it took so long to launch the Lviv branch, how the idea of making coffee in the dark came about, and why the social mission of this project is so important.

‘In the dark, everyone comes to their own conclusions.’

It all started when Alina Marnenko, working in IT, was looking for a ‘project for the soul.’ She wanted to create an escape room that would let people truly immerse themselves in another world. Alina and her friends came up with a script and concept and began investing the money they had earned in IT.

But then Alina's partners went abroad, went on a tour in the dark, and came back with impressions that changed their plans. They realised that quests, however interesting they may be, lack depth and long-term meaning. A museum in the dark combines two things: entertainment and a strong social impact.

‘I'm not a fan of lectures or sermons,’ Alina explains. ‘Coming to people and preaching to them how to live is an ineffective approach. But in a museum in the dark, everything happens organically, naturally, and everyone comes to their own conclusions.’

Before opening the museum, Alina Marnenko quit her day job, planning to return once everything was organised. The museum's co-founders saw it as a hobby that would only require temporary involvement. It turned out differently: the project has been her main occupation for eight years now.

It was obvious to Alina that people with visual impairments should be the guides at the museum. She had no personal experience working with people with visual impairments, so she turned to an organisation that helps people with these issues.

‘I went to the Ukrainian Association of the Blind. I arrived at the meeting and realised the director was also blind, which made sense but surprised me. He said that I was not the first person to come up with this idea, but no one had ever launched such a museum. He added that the idea was great, but in his opinion, only people with visual impairments would have enough motivation to implement something like this,’ she recalls.

However, the association’s head shared the contact details of people with visual impairments. They were invited to focus groups and brainstorming sessions. There, they expressed witty and even harsh ideas, such as leaving manholes open on the museum floor. Alina realised that behind these jokes were real problems that people with visual impairments face every day.

Several focus group participants volunteered to be museum guides. Alina recruited others through advertisements and personal contacts. The selection process was difficult: not every person with a visual impairment was ready to work as a guide. This job is stressful, emotional, and requires responsibility for the group. For the founder, it was important that each guide shared the project's values. After all, the guides, together with management, participate in creating new formats, testing them, and setting the tone for the entire project.

‘I Can't Explain What It Was Like, Just Come’

The first paradox the team encountered was that the museum was supposed to break down stereotypes about people with visual impairments, yet it was precisely those stereotypes that kept people away. Alina Marnenko says many people were afraid to interact. They imagined that the tour would turn into a story of the guide's suffering. When they came, they were surprised: the guides joked, laughed, and told entertaining stories.

The museum has several locations from everyday life. ‘It was important to recreate each one very realistically,’ explains Alina. ‘People need to feel the sounds, temperature, and smells. That's why, for example, we have real cobblestones on the street and traffic lights. The guide gives certain tasks, but they are organic: first, they cross the road, then they find something, then they go somewhere. These tasks are designed to draw people's attention to important things — for example, they bump into something parked on the sidewalk and understand what a problem this is for people with visual impairments.’

She says that the first minute when a person is plunged into darkness is a shock to their brain. It takes time to start perceiving information through other senses and to try to do familiar things without visual guidance. By getting rid of stereotypes about blind people and putting themselves in their shoes, people feel a strong emotional connection with the guides. ‘The roles are reversed: while we usually perceive people who cannot see as people who need help, in the dark, visitors rely on the guide, and they are the ones who need help and have to learn to entrust themselves. Many people end up hugging after spending an hour and a half together in the dark,’ says Alina.

Promoting Ukraine's first museum in the dark was not easy: people did not understand what it was, mistook it for an escape room, and thought it would be boring. Word of mouth worked best: those who had already been on the tour advised others, ‘I can't explain what it was like, just come.’

From museum to foundation

Over the years, the museum began offering more than just tours. Street walks, dates in the dark, quests, and master classes were introduced. At the same time, the social aspect evolved: the museum focused on accessibility, training rehabilitation specialists, and expanding opportunities for people with visual impairments.

When the full-scale war began, Alina Marnenko initially thought that the museum would have to close: leisure activities seemed inappropriate. But people wanted meaningful experiences and opportunities to take their minds off the situation. In addition, more and more people were losing their sight due to the fighting, and Ukraine lacked quality rehabilitation. Therefore, in 2022, Alina officially registered the 03:00 Foundation.

The foundation focused on creating opportunities for people with visual impairments and improving accessibility. Alina's fundamental approach is not just to engage in charity, but to create opportunities. ‘All people with visual impairments are offered to become massage therapists or assemble clothespins in basements,’ she explains. ‘This is the wrong approach, because people with visual impairments, just like sighted people, are all different. They want to do different things. That is why we are creating different opportunities: sports, education, culture, and services. Everyone should be able to choose what they like.’

The museum has remained a social enterprise and a tool for changing attitudes because people leave the tours with a desire to change the world around them.

‘Every time, some kind of apocalypse happens’

In 2019, when the museum in Kyiv had already been operating for several years, the idea of a branch in Lviv emerged. The team announced the opening and began searching for premises. The plan was disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced the temporary closure of the Kyiv space. Unlike other cultural institutions, the museum in the dark could not simply move online. However, they found a way out. ‘We launched online interactive activities with our guides for children. Then we organised a street walk. And in August, we reopened the space,’ Alina recalls.

In 2021, the team was preparing to launch again, only to be interrupted by the beginning of the full-scale invasion. ‘We joked that every time we announce an opening in Lviv, some kind of apocalypse happens,’ laughs the museum director. Now the team had a plan to move the Kyiv museum to Lviv.

In June 2022, Alina found premises at 8 Lychakivska Street in Lviv and began renovations, with the opening planned for the fall. But in the fall, Russia began attacking power plants. ‘Opening a museum in the dark during blackouts was a bad idea,’ says Alina Marnenko. ‘People didn't like the darkness. Guided tours in Kyiv were also suspended. It was a very difficult situation: I had two rented premises, a large team to support, and none of the museums were open.’

To survive, the guides began making and selling beeswax candles. This helped them get through the difficult times and keep the team together, and artisanal wax products remained a hallmark of Three After Midnight. When the situation stabilised, the Lviv branch was opened, and the Kyiv branch resumed operations.

A Lviv café in the dark

In Lviv, the team began to work more with new formats: dates in the dark, street walks, and events. ‘There is this location called “cafe”,’ Alina says. ‘I really wanted to recreate a real Lviv coffee shop. We tried different options, considered capsule coffee machines, but that's not the right level.’ During another brainstorming session, someone asked if the guides could make coffee right on the tour using professional equipment. The team found partners — Campus Coffee School — to test the accessibility of all stages of coffee making for the blind.

‘And here we discovered that it is not just accessible, but that blind people are often more attentive to sensory details. Baristas often rely on the visual component, but in reality, for example, when you whip milk, it is important to control the temperature with your hand, not just look at the foam. A lot has to be analysed by sound. Our guides were enthusiastic about the idea and began to encourage us to implement it,’ says Alina.

Thanks to a grant from the House of Europe, the Three After Midnight museum in the dark in Kyiv set up a professional coffee corner. The barista school held training right in the museum, and each participant had to prepare many drinks to build their skills. At the same time, they gathered a community of baristas who came to train the participants and share their experience.

Six of the seven Kyiv guides wanted to learn. Now, each of them is interning at a separate coffee shop. And if they wish, they can continue their cooperation in the future. Alina says that the first group was a pilot group, whose task was to test the training program, its duration, and the internship process. Based on the results, a final programme will be developed and a group recruited for employment. ‘Next, we plan to expand this project to other cities, including Lviv,’ says the museum director. ‘I have already spoken with coffee shop chains, and they are interested. There is also demand from people with visual impairments who would like to learn a new trade.’

One hundred cups of cappuccino

Viktoriia Shevchuk has been working as a guide at the Museum in the Dark for over eight years. For her, this job is a way to show people her own life. Many visitors come to the museum ‘just to have fun,’ says Viktoriia, but they still leave with a new experience: ‘they start asking questions, realising things they hadn't thought about before.’

Once, a girl approached Viktoriia in the subway, offered her help in the right way, and said that she had learned this during a visit to the Museum in the Dark. ‘It was clear that she was doing this for the first time, but she knew how to ask the right questions and how to help. I was very touched,’ recalls the guide.

When the opportunity to train as a barista came up, Viktoriia Shevchuk jumped at it. ‘I love learning and discovering new things,’ she says. ‘Besides, it was interesting: why is coffee different in different cafes, and what should it be like? I had no idea what a professional coffee machine was. I thought it was something simple: just press a button and that's it. But it turned out to be quite complicated.’

While the guides were practising, Viktoriia went to a rehabilitation centre where she works with soldiers who have lost their sight. When she returned, each student had already prepared 20 cups of cappuccino. In total, they had to prepare 100 cups. She had to catch up.

The biggest challenge was learning how to froth milk. ‘People who can see can look at it, but I have to understand it by the sound and feel in my hands,’ explains Viktoriia. ‘I thought I would never learn how to froth milk properly. When I pour it, I can feel by the weight that it’s enough.’

Once she had finished her training, Viktoriia began an internship at the Campus Coffee café on Poshtova Square in Kyiv. ‘I really enjoy making coffee, especially cappuccino. It's incredible when you serve people, and they enjoy it. I stood behind the bar and realised: I really like this,’ she says. Viktoriia has not yet decided whether she will pursue both her work as a guide and as a barista, but she considers this experience to be important.

Alina says that making coffee can be not only an additional job and a way for people with visual impairments to socialise, but also a powerful public example. After all, when visitors see a barista with visual impairments in a coffee shop, it breaks down stereotypes.

Support that enables change in society

The project to train guides with visual impairments to become baristas was one of the winners of the Creative Business Boost open call, held by House of Europe for the second year in a row. Its goal is to support creative businesses that need to change, strengthen, or develop new areas, and to create conditions for their growth.

Grant manager Oleksandr Drachuk says that the second wave of the program was launched in the spring of 2025 and received 249 applications. ‘The Museum in the Dark passed all stages of selection, which was carried out by an independent jury of 12 experts — representatives of various creative industries with experience in evaluating grant applications,’ says the manager. ‘Their task was to assess the maturity of the business, its growth potential, and the feasibility of its planned activities. The 15 businesses that scored the highest became participants.’

The support included not only funding but also consultations with Ukrainian experts and participation in an international webinar featuring experts from Denmark, Germany, Italy, and Sweden. The project results showed that working with mentors helps entrepreneurs review their business plans and strategies, understand how to move forward, and survive in the market during difficult times.

According to Oleksandr Drachuk, the grant yielded several tangible results for the Museum in the Dark. ‘First, they purchased coffee-making equipment that people with visual impairments can use to train and work. It will continue to be used. Second, they set up internships for baristas with visual impairments at coffee shops in Kyiv. Third, they created an inclusive space for baristas to learn and work,’ the manager lists. ‘The House of Europe team is pleased that the Museum in the Dark has been able to use the grant money effectively and get the most out of participating in the project. Most importantly, this is not a one-off project: the museum will continue this idea as a permanent part of its business.’

House of Europe's priorities include equal opportunities, inclusion, working with ethnic minorities, and more. According to Oleksandr, promoting inclusion in the creative sector has great potential, though the challenges are many as well. ‘I want to believe that people are becoming more attentive to each other, more tolerant,’ says the House of Europe representative. ‘It is good that there are programmes that support not abstract ideas, but real projects that are already working and can serve as examples of how to develop honest and responsible business.’

This material was created as part of the Goals That Hold Up special project, which tells the story of the House of Europe's achievements over the past year through personal stories.

Франциска Сімон

Франциска Сімон