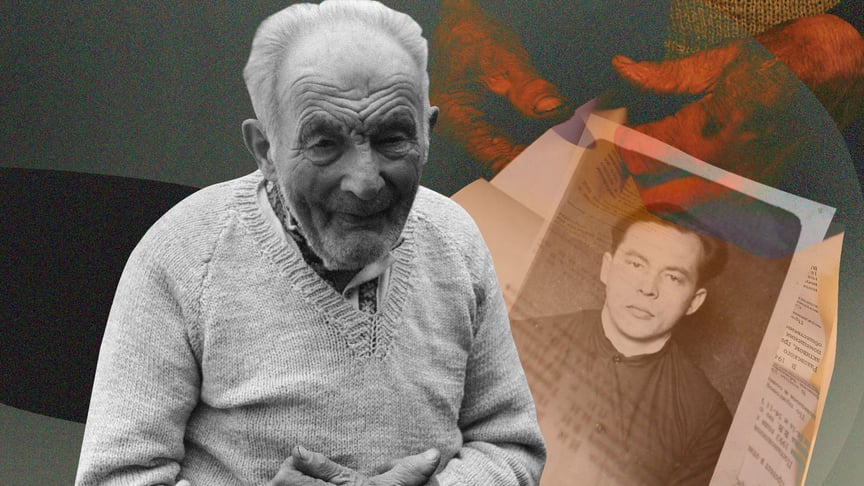

22-year-old lad returned as a 47-year-old sickly man. The only living political prisoner who served 25 years

"This is a terrible war, much worse than World War II. So many dead, and even more maimed! The only thing that comforts me is that we are on the bright side," says 94-year-old Ivan Myron, with tears streaming down his face between his wrinkles.

The only surviving Soviet "25-er" cries every time he talks about the soldiers. Yet he recalls his past almost without tears: participation in the Ukrainian underground, arrest, transfer to the Gulag, punishment cells, hellish work in camps, hunger strikes, and rebellions in barracks. Ivan served 25 years in Soviet camps, from the first to the last day. Whenever he was offered a pardon for admitting his guilt, he never accepted it.

The house is six years younger than its owner

I come to visit Ivan Myron on a Saturday. The day before, I contacted the social worker who helps him and his wife, asking if Ivan is in good health and can meet with me.

Hanna Tafiychuk says that her client's legs are very swollen and his heart is not well. She says that she has bought some medicines, but he does not take them regularly and does not want to go to the hospital. Nevertheless, when he heard about the guests, he was happy and asked me to tell him that he would be happy to receive them.

So I buy some decent tea (after 25 years in the camps, the former political prisoner's taste preference is strong black tea without sugar) and some goodies to go with it, and in a few hours, I'm already at Rosishka, on the Potik.

Potik is the name of the hamlet where the Myrons have lived for generations. The 94-year-old Ivan, like his father once did, keeps sheep and goats here, still milking them himself every day, giving them to shepherds in the spring to go to the meadow, and waiting for them at home in the fall.

"If you came in March, you would see a bunch of lambs in their house, it's so beautiful!" says Hanna Tafiychuk.

An old garden grows around the small Hutsul house with two rooms on the hills, some of the trees were planted by Ivan’s father. He also built the house where Ivan and his wife Khrystyna live now. Built in 1935, the house is six years younger than Ivan Myron.

"I would have fought for Carpathian Ukraine, but who would have accepted me, a kid, back then?"

While Hanna is making tea, we sit down to talk. I say that I will take pictures, and Ivan gets up to change his clothes. He returns 10 minutes later in a traditional Hutsul embroidered shirt and an old jacket. He sits down at the table and begins to recall everything that he has been through.

Ivan was born in 1929, so at the beginning of World War II he was a 10-year-old boy and remembers everything well.

"We didn't even feel that war, so to speak. I was a kid then, I went to school. Before the war, we learned three anthems at school: Czech, Slovak, and Ukrainian (the anthem of the Subcarpathian Rusyns by Aleksander Dukhnovych, which was sung during the autonomy of Czechoslovakia, which included Zakarpattya between the world wars and then during the short period of independent Carpathian Ukraine - ed.), recalls Ivan Myron.

The most terrible episode of that war for him was the destruction of Carpathian Ukraine by the Hungarians. He recalls that he really wanted to join the Sich to defend the state, "but who would have accepted me, a kid, there?"

"We talked about those events a lot in our home, and many Sich members came to us and hid. Later, during the occupation, there was a time when a German settled in Bychkiv and smuggled Sich members who were in an illegal status to Germany for money. Many of our people escaped that way.

But one relative, Hanna, did not want to go to Germany and went to teach in Lazeshchyna, and someone there reported her. She was warned about being detained, but she decided to run away with the local communists to the Russians. They were imprisoned there: the communists were given a year each, and she served five years because the Russians were told that she had been in Prosvita," says Ivan Myron.

"Occupation replaced occupation"

In fact, Myron's family lived through the entire Hungarian occupation during World War II as they had before the war: they worked on their land. His father had cows, oxen, and sheep. Ivan spent summers with them in the meadow.

He also went to school. He completed five years in Rosishka, then studied in Bychkiv. After the arrival of the Soviet troops, in 1944, he studied at the Mukachevo Agricultural College.

"Occupation was followed by occupation," Ivan Myron explains that time.

Between 1944 and 1946, a political entity called Transcarpathian Ukraine operated in Zakarpattya, where Czechs from the exiled Beneš government and local communists fought for power. The latter eventually prevailed, and in 1946 the region became part of the Ukrainian SSR as one of the oblasts.

"That was the time when we lost even our name - until then we were Subcarpathian Rus, Carpathian Ukraine, then Transcarpathian Ukraine, and then we became just a Zakarpattya Oblast within the Soviet Union. The word ‘Ukraine’ did not even feature for us anymore," says the former political prisoner.

He chose the illegal status of an insurgent

During the lessons at the agricultural college where Ivan was studying at the time, they began to talk about the charms of the new government and solemnly announced that the students would have the honor of forming collective farms in Zakarpattya.

"When I heard that, I felt so sick! I knew what these collective farms were, and I decided that I would never do that. I will not take away people's land, because God gave it to people from time immemorial. So I fled from Mukachevo to my home.

It was spring, I spent the summer with my father in the meadow, and in October a teacher from Bychkiv came to my father and told him not to keep me at home, because it was a pity to lose such a mind. So they sent me back to school to get a full education. I eventually finished 10 grades. Then I went straight to teaching. I became a primary school teacher in Chorna Tysa."

That was until the fall of 1949, when Ivan Myron received a draft summons. He recalls coming home with that piece of paper and telling his mother that from now on there was no place for him anywhere else but in the OUN-UPA underground.

Ivan Myron became a liaison in the UPA under the pseudonym Malyi, despite the fact that his brothers-in-arms immediately warned him that there was no hope for further war, and they would all be caught in the forests and sent behind bars. In fact, Ivan Myron was caught in April 1951, after an attempt to seize weapons in the village council in Rosishka, when he disarmed a guard and seized three carbines.

On a traitor's tip-off, their insurgent group of 18 people was captured by the SS during a raid three months later. Six insurgents from this group, including Ivan, were sentenced to 25 years in camps.

"I do not consider the defense of my people a crime"

According to the political prisoner, he was sentenced in Uzhhorod on Christmas Day 1952. At the time, Ivan Myron was 22. The next 25 years, which were supposed to be the best in his life, would turn into hell with inhuman living conditions.

The worst was before Stalin's death: hellish, almost round-the-clock work in the eternal cold without days off, constant searches and punishment for the slightest disobedience, he recalls.

At the time, Ivan Myron was serving his sentence in the camps of Norillag. In 1953, he took part in the Norilsk Uprising, which lasted over two months and eventually changed the system: prisoners got four days off a month and the opportunity to send and receive letters every fortnight (before that, it was possible only twice a year).

Subsequently, in several waves (in 1956, after the de-Stalinization, and in 1960, when the criminal code was changed and the 25-year prison term was abolished, reducing it to 15 years), tens of thousands of political prisoners were released from the camps. But not Myron.

Every time he was summoned by the commissioners and offered to sign a confession, Ivan said that he did not agree with the accusation and did not admit his guilt.

"I told them: 'I am not a criminal, because I do not consider the defense of my people a crime’. Later, they simply stopped summoning me for these confessions," he recalls.

Therefore, Ivan Myron served all the 25 years in the camps that the regime sentenced him to. Now he jokingly says that he did not serve his time in full, because when he was transferred by plane from Moscow to Uzhhorod, it was a Saturday. Myron was released on the same day, because Sunday was a day off, and they couldn't hold him until Monday.

"My sentence expired on Sunday, and I was released on Saturday in the evening, so I was released six hours early," he says.

Awaiting rehabilitation

Ivan recalls traveling with his brother by bus from Uzhhorod to Rosishka. How he looked at women and children eating ice cream on the streets and could not believe his eyes.

He returned to the village from which Ivan Myron was taken as a 22-year-old boy as a sick 47-year-old man. He was labeled an "enemy of the people" (he recalls how people did not sit next to him on the bus and not everyone greeted him on the street), with the possibility of working only as a stoker, monthly police reports and checks of all correspondence.

Ivan's mother did not live to see him as she died two years before his return. He began to live in his parents' house. This was the place where the Greek Catholic Church used to gather for secret services during the underground period. At one of these secret services, Ivan met his future wife Khrystyna Hrytsak.

Though not wealthy, they have lived together in comfort, with respect, support from family and friends, and occasionally kindness from strangers. For example, in November, Lviv Plast members raised funds and paid craftsmen who installed hot water in the Myrons' home.

Ivan had to wait almost 30 years after Ukraine's independence to be rehabilitated. This was done only in August 2019 under the new law "On the Rehabilitation of Victims of Repression of the Communist Totalitarian Regime of 1917-1991."

He retrieves a document from a pile of papers near the table: "See what it says here? It says that I have been rehabilitated, but the sentence of that court in 1952 has not been canceled. That sentence, under which I was unjustly convicted and under which I served in the camps, was never canceled. I never received justice!"

"Defending your land and people is a holy cause"

Now there is also a war in Ivan Myron's house: he follows the news on TV with zeal. He says he has been waiting for this full-scale war.

In 2014, when he was almost 10 years younger, he sometimes asked to be taken to the front. He said he was not fit to shoot anymore, but he would have passed the guys ammunition and shells. Nowadays, he helps the army mainly with words and... cheese. He sends it to the front through volunteers.

At the cemetery near the church in Rosishka, blue and yellow and red and black flags fly on two graves. One of the men buried here died at the front, the other died in hospital from his wounds.

Back in April, Ivan Myron's nephew, Andriy Kostiuk, went missing in Bakhmut. He served in the 101st Transcarpathian Tank Company.

"He was such a nice guy, he helped us so much," laments Khrystyna, Ivan Myron's wife. "He was here in the spring, helping us clean the garden and chop firewood. And for more than half a year we have not heard from him.

He is officially ‘missing’. But the guys told us that there was a heavy shelling there, and part of the house was left under the rubble. But we pray for him and keep believing that he is alive and will come back."

Ivan cries every time we talk about the current military.

"I pray for them every day and ask for their protection. But I can't help them... We have to stop the beast. We have to be dignified and fight back. Defending your land is a holy, great deed.

The more people undergo military training, the more Ukrainians take the oath of allegiance to their people and state, the bigger our army will be, and the fewer thieves and traitors there will be in society. We have to become such a people, a dignified people!" he says.

Ivan knows exactly what dignity is and how costly it can be.

This article is part of the Children of War special project, in which we tell the stories of Ukrainians who witnessed the Second World War or its aftermath as children and are now experiencing another tragedy in their old age.

This piece was created as part of a project funded by the German Federal Foreign Office to support Ukrainian independent journalism.

Author: Tetiana Kohutych

- Share: