76 days in the occupied Crimea: how we returned the abducted child

This story is about Ukrainian collaborators and the highest political leadership of Russia. They did everything they could to kidnap 105 children from the Oleshky boarding school. Among the children was 9—year—old Mykyta Bilanchuk. We helped his grandmother find the boy and did everything possible to ensure that the grandmother and grandson met. Read what happened in the hromadske investigation.

The great abduction

At the beginning of the full-scale invasion, there were 65 minors and 40 adults in the Oleshky boarding school for children with disabilities. Children were sent to this institution in the Kherson region either for treatment or on vouchers, like in a sanatorium. There were also children with disabilities who did not have parents.

In the first months of the occupation, the Russians did not allow the children to be taken out of Oleshky. At the same time, Tetiana Kniahnytska, the director of the orphanage, refused to cooperate with the occupiers, although she was encouraged to do so by collaborator and former MP from the Party of Regions Oleksii Zhuravko. He was also a graduate of the Oleshky orphanage (Zhuravko died in September 2022 – ed.). Kniahnytska held the position for eight months, but then the occupiers simply kicked her out. They appointed Vitalii Suk, the former director of the Kherson driving school Svitlofor, to her position.

“Why do they even appoint new people? Because the old people didn't want to cooperate with them,” said Vadym Reutskyi, a teacher at the institution.

The occupiers needed Suk to sign the documents. It was with his permission that in October 2022, the Russians began to take children in groups to occupied Simferopol and then to Russia.

“On October 21, 16 children were taken away. They were taken first to Crimea, to a hospital. It was the Clinical Psychiatric Hospital No. 5, Simferopol district, in the village of Strohonivka. Then the second batch was taken on November 4 – the children were also taken to this hospital. As I understand it, this was their base, they were either examining or… Well, the conditions in which the children were kept there were terrible. And when the rest of the children arrived there on November 4, they did not see the 16 who were taken the first time. That is, they had already been sent to the Krasnodar Krai at that time,” said Vadym Reutskyi.

In April 2022, hromadske journalists began to establish and verify the lists of the children who had been taken away from the institution. We found out that more than half of the children were in extremely serious condition, so moving from place to place could harm them. So we started identifying each child, his or her diagnosis, and location.

The Save Ukraine Foundation agreed to organize the return of the children together with us. After we received and checked the lists, talked to witnesses, and found out when and where the children were taken, we started looking for their relatives. One of the calls was decisive.

From occupied Oleshky to Krasnodar

Polina Kindra is the grandmother of 9-year-old Mykyta Bilanchuk, who was taken by the Russians from the Oleshky boarding school along with other children. At the beginning of the full-scale invasion, the woman lived in Poland. She had long dreamed of taking her grandson to live with her but was unable to do so. Together with her and the Save Ukraine Foundation, we began to plan a trip to the occupied territory in detail.

On June 14, 2023, Polina Kindra and I left the Polish city of Katowice for Kyiv. On the way, the woman told us that the boy had a mom and dad. Mariia, Mykyta's mother, moved to Egypt in 2021 in search of work and was not interested in the boy. He was raised by Valentyn, Polina's son, although Mariia did not list him as a father on Mykyta's birth certificate.

“When she got pregnant, I was there for her. Because I wanted a grandson or granddaughter – this is the closest person to me. My husband died of a heart attack at the age of 42. We lived with him for 13 years, and then he died in August. Masha was pregnant, and we went to the hospital. Masha was told: ‘It's too much water, we have to get rid of the fetus’. I said: ‘No’. And I begged God for the baby to be born. And Mykyta was born: 2 kilograms, 44 centimeters,” Polina said.

In 2019, the woman went to Poland to work. Mykyta lived with his father Valentyn in Kherson. Six months before the outbreak of the Great War, the boy, who has muscle weakness and digestive disorders, was placed in the Oleshky boarding school to improve his health before school.

After the occupation of Oleshky and the deportation of the orphanage, Polina searched for her grandson, interviewing friends and calling children's institutions in Simferopol. In the fall of 2022, she managed to find him – 16 children were taken to the village of Strohonivka in occupied Crimea.

“I called them. They said: ‘Yes, he is here. But he won't be [here] for long. We will examine him for now’,” Polina recalls. After that, Mykyta was taken to Krasnodar, Russia.

“I sent them a photocopy (of Mykyta's birth certificate – ed.). They asked me the year of his mother's birth. I said that she was born in 1993... I said: ‘His mom is in Egypt. His dad is under occupation in Kherson. I, his grandmother, am in Poland.’ They said: ‘But the file says that he has no one. His mom is missing, his dad is at war or dead.’ I said: ‘There is a grandmother. I am his grandmother’,” the woman says.

Then, on November 15, 2022, she was allowed to talk to her grandson on the phone. Mykyta was 9 years old.

“I called and they let me talk. And very quickly, very quickly, he told me: ‘Grandma, a boy is bullying me.’ I said: ‘Tell the boy he can't fight.’ He said: ‘Grandma, will you take me away?’ I said: ‘Of course I will! I'll earn money and take you back’ ,” says Polina.

However, very soon the connection with the child was cut off. Polina began to suspect that her grandson had been taken from Krasnodar to an unknown destination. She had to start the search from scratch.

“I heard, I saw that children were taken to Skadovsk from Krasnodar. And I said: ‘Maybe he's in Skadovsk?’ [In Krasnodar] they said: ‘No, he's not in Skadovsk, we checked.’ Where is he then? They didn't tell me for two days. I called, insisted, and wrote: ‘Tell me, please, where is he? Just write, is he in Skadovsk? Yes or no?’ And they wrote to me: ‘Yes’,” says Polina.

From occupied Skadovsk to occupied Dzhankoi

The woman was determined to take her grandson, bring him home to Poland, and raise him with her common-law husband, Zurab. After we confirmed that Mykyta was definitely in Skadovsk, Polina came to Kyiv. Here, together with Save Ukraine volunteers, we prepared the necessary documents and planned the route, and the woman went to pick up the child. We agreed that we would be in touch every day. We were convinced that the documents were in place, so it would be possible to return Mykyta quickly.

Polina traveled through Poland to Belarus, then through Rostov, occupied Dzhankoi and Armiansk. This is how she got to occupied Skadovsk. On June 23, she arrived at the facility where her grandson was being held.

“They are not giving me Mykyta back. There is a mistake in the documents, and I am staying for two more weeks. I can't take my grandchild because this director has taken custody of him. I said: ‘On what grounds did you take him? I am his grandmother.’ And the director said: ‘I'm going to kick you out of here, you're on my territory.’ Well, I'm silent because I can't because I understand everything perfectly well,” the woman sent this voice message to the hromadske on June 23.

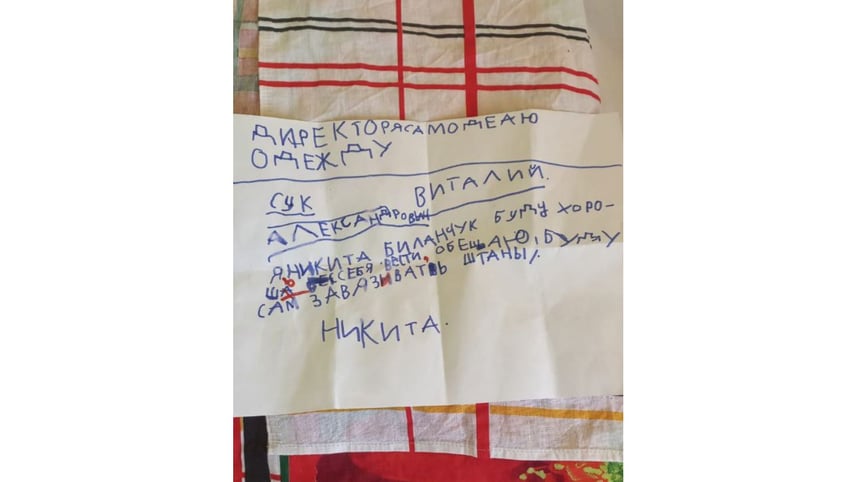

That's how we found out that Mykyta, who has parents and relatives, had already been taken under the care of the “director” of the Oleshky boarding school, Vitalii Suk. The boy was automatically granted Russian citizenship. Polina noticed that Mykyta began to behave strangely. “They either give him some injections or some other medicines. They said that when children start to freak out, scream, they give them something…” the woman said.

While in the institution, she learned that two of its students had died. Our source confirmed this. An adult student and a 6-year-old boy died. This information was carefully concealed by the Russians.

Meanwhile, realizing that they would have to fight for Mykyta, Save Ukraine volunteers found a temporary shelter for the woman. Polina moved to a house of worship in the occupied Crimea. It was the closest relatively safe place. There, Polina stayed in touch with us, volunteers, and Russian lawyers who then became involved in the story. They were supposed to help Polina deal with the demands of the occupation administration and contact Russian officials on her behalf.

DNA examination

Meanwhile, the so-called director of the boarding school, Vitalii Suk, demanded a DNA test from Polina. The results were supposed to be ready in 2-3 weeks. On July 3, in occupied Oleshky, a DNA sample was taken from Mykyta. Polina took a DNA test in Simferopol. Both samples were brought to Moscow on July 8. At that time, the woman had been in the occupied territory for two weeks.

Two weeks later (and even after three), there were no results of the examination. Meanwhile, in the occupied Crimea, the locals convinced Polina that Ukraine had attacked itself. And her grandson was not kidnapped, but rescued.

“They are all zombies. They say that Ukraine attacked. I say, how did Ukraine attack itself? I say Ukraine attacked, and Ukraine is also taking children to Russia? How did he end up in Russia? They say that Ukraine is shelling, and Russia is taking the children to a peaceful place. That's how zombified they are. They say Russia is good, they live so well. And how do they live? It's horrible how they live. They live in sheds, simply sheds,” thewoman said.

Only on August 3, a DNA examination confirmed that Polina Kindra was Mykyta Bilanchuk's grandmother. But then a new demand was made – Polina must take Russian citizenship. They said that this was the only way she could take the child under her care. On top of that, she was forbidden to communicate with Mykyta.

“Hello. Mykyta has been under psychological stress for a week. Namely, he has been experiencing anxiety, anger, apathy, and aggression. Our specialists are providing him with psychological assistance. The doctor does not allow any psychological stress yet. Therefore, we will refrain from talking today, we will postpone it," theso-called director of the boarding school Vitalii Suk wrote to Polina.

In mid-August, Russian lawyers explained to Polina that she could not actually obtain a Russian passport and guardianship under Russian law. Thus, Vitalii Suk was looking for excuses to keep Polina and the child in Russia forever. Polina was forced to apply to the occupation guardianship authorities, the relevant occupation ministry, and representatives of the Russian Ombudsman for Children's Rights. Formally, they allegedly agreed that there were enough grounds to give the child to the grandmother. But Suk refused to give Mykyta back.

Eventually, the “deputy minister of labor” of the occupied Kherson region came to pick up the boy with Polina. On the night of August 20, the women left for occupied Skadovsk.

However, on August 21, Polina texted the editorial board: “Everything is bad, they are not giving him back. What do they say? To take a Russian passport... I had to apply for guardianship in Poland. How could I do that if he was hidden? I don't know what to do. She (the “deputy minister of labor” of the occupied Kherson region – ed.) is now deciding. They say I will return to Dzhankoi.”

In the evening of the same day, Polina returned to occupied Crimea. After two months of living in occupation and after dozens of attempts and negotiations, the situation has reached a dead end.

“He knows the Russian flag, but he doesn't know the Ukrainian flag…”

Mykyta was returned to Polina suddenly. On September 1. As if the previous two months of hell and constant lies from all sides had not happened. The so-called director of the orphanage, Vitalii Suk, and personally the Russian Commissioner for Children, Maria Lvova-Belova, who is on the international wanted list for abducting Ukrainian children, finally decided to hand Mykyta over in front of a dozen cameras.

“I walked in. And I just saw Mykyta. I thought that if Mykyta was brought in, he would be given back. The director stood up, eyes down. We signed the documents with Levova-Belova to take the child away. Because I said: ‘Give me security so that our car will not be shot.’ We got into the car with Mykyta, arrived in Crimea, and spent the night. And then we went to Poland,” said Polina.

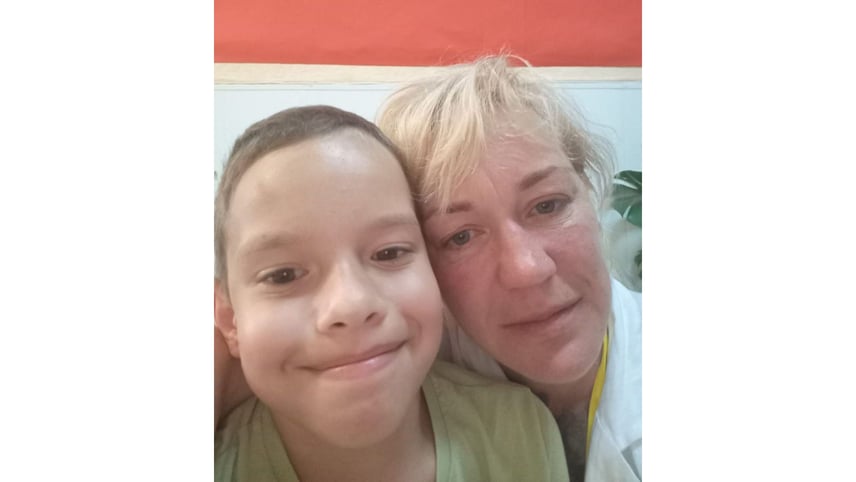

A week later, the woman and her grandchild were in the Polish city of Katowice, where we met. Mykyta does not say anything about life under occupation.

“He was not like that. As the psychologist says, you can't touch him. He has to get over everything… If he knows the Russian flag, but he doesn't know the Ukrainian flag… He hasn't said anything yet,” explained Polina Kindra. Now the boy is undergoing medical examinations, and Polina is preparing all the necessary documents for the guardianship.

“Grandmothers, aunts, uncles, [all] those whose children were taken away from them just have to endure it. They put a lot of pressure on the psyche. If you can stand it, you will take your child back. If you can't stand it… They will break you,” Polina says.

- Share: