“Get out of here, my scope can see further than your camera,” a Russian said. How Crimea was annexed 10 years ago

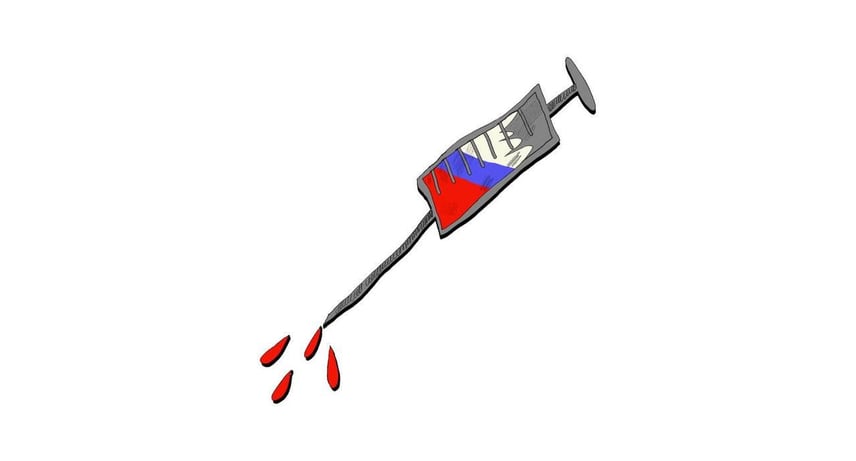

February 20, 2014 is on the calendar. The world's attention is focused on the bloodiest events on the Maidan in Kyiv during the Revolution of Dignity. On the same day, the first recorded cases of the Russian armed forces crossing the border of Ukraine in the Kerch Strait and involving units of the Russian Armed Forces stationed in Crimea occurred.

In 2015, the Verkhovna Rada would officially recognize this day as the date of the beginning of the occupation of Crimea. The aggressor would not pretend either — by that time, Russia had already cast departmental awards of the Ministry of Defense “For the Return of Crimea” with the dates “20.02.14 — 18.03.14” engraved on the reverse. This was the beginning of the occupation of Ukrainian Crimea.

Slow russification

“Before 2014, they tried to occupy Crimea repeatedly,” says Andrii Shchekun, one of the coordinators of the Euromaidan — Crimea movement and organizer of pro-Ukrainian rallies in Simferopol. “We lost when we received the status of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea because it was imposed on us by Russia. It was in fact an ‘autonomous republic of Crimea’ with a Russian majority, funded by Russia. Ukrainians in Crimea needed help and a proper state policy. In 1993-1994, completely pro-Russian forces came to power in Crimea, led by Yurii Mieshkov (the first and only president of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, chairman of the Council of Ministers — ed.), and the war against ‘Mieshkovism’ began. They even introduced Russian time. Pro-Ukrainian Crimeans then rebelled. Another attempt took place during the Orange Revolution, but law enforcement agencies did their job well. The Alpha special group then took control of all the FSB officers who worked for the Russian Federation and cut off their communication.”

Journalist Tetiana Kurmanova, who worked at the Crimean Center for Investigative Journalism in 2014, also speaks about the planned occupation: “Russia has been preparing the occupation for a long time, various scenarios have been worked out. In Crimea, they said that no country should be allowed to feel so free on the territory of another country. There were a lot of Russian military retirees with real estate in Crimea. The pro-Russian military movements felt quite free, and the Ukrainian government allowed it. Russia has always used both the cultural field and the educational field — it was much easier for applicants from Crimea to enter universities in St. Petersburg under quotas than in Simferopol and Kyiv.”

Andrii Shchekun, editor-in-chief of the Krymska Svitlytsia newspaper, predicted in one of his articles that the Russian occupation could take place in 2017. That is, when the agreement on the status and conditions of the Russian Black Sea Fleet's stay on the territory of Ukraine expired. However, Russia was ahead of all predictions.

“Little green men” and the so-called self-defense of Crimea

On February 24, 2014, in Novorossiysk, Russian Navy ships took on board military equipment, the so-called “little green men” — Russian soldiers without the insignia of the Russian Armed Forces — and headed for Sevastopol.

“When people entered Yanukovych's house (on February 21, 2014, Viktor Yanukovych fled Kyiv — ed.), we had hope that everything would change, because the revolution had won,” says Crimean journalist and researcher at the Crimean Human Rights Group Iryna Siedova. “The organizers of the Crimean Euromaidan gathered people in the square to talk about what had happened. Among the crowd, there were FSB agents and infiltrators in civilian clothes. When I was speaking, they started throwing eggs and ran at us. One guy was beaten badly. We managed to hide behind the police, who were still trying to protect us. They told us that they saw local law enforcement officers bought by Russians handing out money to attack us.”

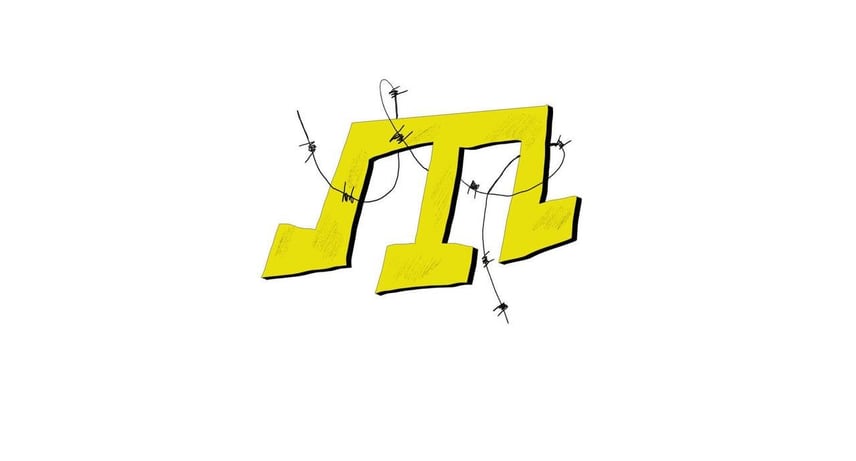

On February 26, local Ukrainian patriots and Crimean Tatars rallied for the territorial integrity of Ukraine in front of the Verkhovna Rada of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea. The date was approved as the Day of Resistance to the Russian Occupation of Crimea.

“About 20 thousand participants of the All-Crimean Peaceful Rally in support of the territorial integrity of Ukraine thwarted the Kremlin's plans with their determination and courage, confirming to the whole world that Crimea is an integral part of Ukraine and the homeland of the Crimean Tatar people,” said Refat Chubarov, Chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people.

A rally of pro-Russian organizations was held nearby. According to some reports, it barely had 2,000 participants.

“In this confrontation, we won the battle against the pro-Russian protesters,” recalls Andrii Shchekun. “We pushed them back and took control of the Supreme Council of Crimea. But our mistake was that we dispersed. The Maidan did not disperse, but we did.”

The next day, unmarked Russian soldiers blocked the buildings of the Crimean parliament and government in Simferopol.

“For us, those who lived in Crimea at the time, the date of the beginning of the occupation was the morning of February 27, when Russian military and armored vehicles appeared on the streets, and the buildings of the Crimean government and parliament of the autonomy were seized,” recalls Andrii Klymenko, project manager at the Institute for Black Sea Strategic Studies. “In the morning, I received a photo of military armored vehicles from my colleagues in Simferopol with the question: ‘What kind of vehicles are these?’ I identified them as Russian armored vehicles of the Tiger type, which were in service with Russian special forces. That is, it became clear that the ‘little green men’ were Russian military personnel. At the same time, I knew that the marines of the Russian Black Sea Fleet in Crimea did not have such vehicles.”

Crimean journalist Iryna Siedova recalls: “The owner of the ferry crossing in Kerch was a Russian. He had railroad ferries that transported trains. He immediately loaded military equipment onto these ferries and brought it from the Kuban to Crimea. The military tried to remove the chevrons, but the license plates on all the vehicles were Russian. We saw all these Grads MLRS coming in. We were threatened and chased for that.”

“As early as 5 a.m., Russian flags were flying in Crimea,” says journalist Tetiana Kurmanova, “The sane Crimeans thought that an anti-terrorist operation would be conducted and that Alpha units would probably arrive. But unfortunately, we did not see it. Instead, we began to observe how Ukrainian military bases were also surrounded.”

Blockade of military units in 2014. The first abductees in Crimea

“Next to the military unit on Subkhi Street in Simferopol, there was a military enlistment office,” recalls Elzara, a lawyer and wife of Crimean Tatar activist Veldar Shukurdzhyiev. “My husband said: ‘I have to go to the military enlistment office, they will be gathering the military right now.’ We passed by the military unit, our young military boys were standing there — there was such fear in their eyes! My husband said: ‘Guys, don't be afraid, we are with you.’ We approached the military enlistment office, but it was closed. When we were walking back, we saw an armored personnel carrier with a burly soldier with a machine gun. My husband asked who they were. He said: ‘Go on, get out of here, walk on by’.”

Tetiana Kurmanova notes: “Everyone was waiting for an answer from the power vertical. Viacheslav Seleznov, who was almost the only official who told us what was happening in the military units, said: we were just told to hold on. Sometimes they said it was probably time to change the cockades on our caps. There was uncertainty. Ukrainian soldiers were blocked by ‘little green men’ in all military units in Crimea. The Russians began to manipulate the military, saying that they had been abandoned, and promising more money. And many people really had that feeling, because even food was not delivered. There was a feeling that Crimea was being surrendered.”

On February 28, 2014, the Supreme Council of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea voted at gunpoint to hold a so-called referendum on the status of Crimea. A representative of the Russian Unity party, Sergei Aksyonov, became the head of the Crimean government. Meanwhile, land entrances to Crimea from the Kherson region were blocked, Simferopol and Belbek airports were closed, and officers of the now-disbanded Crimean special unit of the Ministry of Internal Affairs Berkut appeared at checkpoints.

Elzara Shukurdzhyieva says: “There were many neighborhoods in Simferopol where Crimean Tatars lived. And then literally all the women came out, lined up along the Sevastopol highway. There were thousands of them, with posters and flags. My mother-in-law, who could barely walk, came out too. Even my friend, who was very cautious and afraid of everything, came out. All the women were cooking something for the military personnel: samosas, flatbread, pilaf. The men were on duty at night. It was a desperate desire to change something.”

The Head of the Board of the Crimean Human Rights Group, Olha Skrypnyk, together with her husband and friends, organized the Yalta Resistance Group to help Ukrainian border guards at military units in Masandra and Hurzuf. “We collected information about the movement of Russian troops because the command did not communicate with them in any way. They were abandoned, and the military personnel had no information. We were delivering food and medicine,” she says.

On March 3, 2014, Crimean Tatar activist Reshat Ametov was abducted in Simferopol, where he had come to protest against the so-called referendum in front of the Crimean government building. His dead body with signs of torture was found two weeks later in a forest. Ukraine considers him one of the first victims among those who opposed the occupation of Crimea.

Pressure on activists and journalists in the ARC

“There were already just a few independent journalists in Crimea, and we were immediately put under pressure,” recalls Tetiana Kurmanova. “We had been renting premises in the Trade Union Building on Lenina Square for a long time. ‘The Crimean Self-Defense’ seized our building and blocked journalists. They put us under surveillance. You call a taxi from different phones, but the same taxi driver with a Russian flag arrives. He brings you to your house, and you don't even tell him the address any more. I wanted to go out a block away, and he dropped me off at my place and said: ‘Don’t you know where you live? We know everything.’ It was very telling: we know everyone, we see everything, and we will find you when we need to.”

The work of pro-Ukrainian Crimean journalists was actively obstructed. Most of them had to leave in 2014 because they were not allowed to work.

“I came to the next meeting of this illegal body, and I was not allowed inside. A self-defense officer with an assault rifle began to block the entrance. He said: ‘I'm going to rape you in the middle of this square, shoot you, and not a single person will even look back.’ I looked around and saw a stream of people passing us in a big circle and pretending that nothing was happening,” Kurmanova says.

Journalist Iryna Siedova notes that Ukrainian and international journalists visited, a hub was set up in the editorial office, and local media workers worked as fixers.

“Of course, we were already being followed by FSB officers in cars. In early March, a representative of the journalists' union came with his colleague and we went to film how the Russians were burying APCs under our military units. One Russian soldier came up to our car: ‘Get out of here, because my optical sight can see further than your camera,’ and stroked his Kalashnikov. I realized that there was no point in me throwing my camera at these Russian soldiers,” she recalls.

On March 9, 2014, the leader of the Crimean Euromaidan, Andrii Shchekun, was detained and abducted in Simferopol on the eve of a rally dedicated to Taras Shevchenko's birthday. He was abducted together with his colleague Anatolii Kovalskyi. The prisoners were released only on March 20.

They came to the railway station to meet the Kyiv-Simferopol train. The activists brought national symbols to this action.

“When I approached the conductor, about 50 people jumped on me, twisted me, and took me to the police station screaming. I still managed to make a call and tell them where I was,” Andrii shares his horrific memories, “Then physically fit Russians came up. They said: ‘Let's pack them up’. When I started to resist, I was hit in the head. They put a hood over my head, twisted my arms, and dragged me down the platform. They threw us into a car, beat us more, and taped our eyes and hands. They took us to the military enlistment office, where we found out later that they tortured people: stripped them naked, tied their hands and feet to a chair, electrocuted, and interrogated them. Then the basement was filling up — there were already 30-40 people in it, activists and military. There were some wounded — there was one guy who had his ear cut off because they thought he was a member of the Right Sector. After the exchange, two bullets were pulled out of my arm — the consequences of pneumatic gunfire.”

Olha Skrypnyk, Head of the Board of the Crimean Human Rights Group, says: “On the night of March 15-16, the Russians stormed one of the last units. The Defense Intelligence officers came to my husband and said that the next day was the last day when I could still be allowed to leave. Otherwise, they would not find me.”

Illegal referendum and last pro-Ukrainian actions

On March 16, 2014, the so-called referendum on the status of Crimea took place. The orchestrated and boycotted event contradicted the Constitution of Ukraine and all legal norms. It has not yet been recognized by the international community. On March 14, 2014, the Constitutional Court of Ukraine declared unconstitutional the resolution of the Supreme Council of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, according to which the event was held.

“I still managed to visit these fake polling stations, I saw what was happening in Yalta during the so-called referendum,” said Olha Skrypnyk, Head of the Board of the Crimean Human Rights Group, “It was a referendum under machine guns. In all cities, there were Russian military, ‘little green men’ accompanied by the intelligence officers. At that time, Ukrainian channels were turned off, everything was covered with Soviet-style advertising, and all advertising space was seized.”

According to journalist Tetiana Kurmanova, ballots were issued to everyone without requiring any identification documents.

“It's a farce — they wrote down a person's name and gave them a ballot,” says the media worker. “My colleague recorded people arriving by bus and throwing in ballots. There were no attempts to create anything resembling a real vote. These falsifications were scaled up, they violated their own rules of the game. Of course, journalists were not allowed to the polling stations, and Crimean journalists of the ATR were attacked. There was information about the beating of film crews”.

At 11 p.m., people were going door to door saying that it was still possible to vote. “I saw through the peephole of the door how they were writing these names themselves. They even put in my neighbor's name, who did not go. When I started shouting that it was illegal, they tried to break my door. Those who did not go to the ‘referendum’ were visited at home by Russian police and forced to vote. It was arbitrariness,” states Tetiana Kurmanova.

On March 25, 2014, the Navy minesweeper Cherkasy, the last military unit with a Ukrainian flag in Crimea, was seized. The Autonomous Republic and Sevastopol were fully occupied by the armed forces of the Russian Federation. However, Ukrainian activists continued to stay in Crimea.

Crimean political prisoners

Persecution of Crimeans for their political views, ethnicity, or religion continues. As of March 13, 2024, the occupiers have illegally imprisoned 214 people, 135 of whom are Crimean Tatars. In February 2023, two political prisoners, Kostiantyn Shyrinh and Dzhemil Hafarov, died. Moreover, since February 24, 2022, Russian security forces have opened at least 699 cases under the article on the so-called discrediting of the Russian army in Crimea.

“These are terrible figures because we are talking about the illegal conviction of Ukrainian citizens. Among them are activists, human rights defenders, and civilian journalists — those who have remained patriots of their country to the end and are not ready to put up with the occupation regime. From the very beginning of the occupation, Russia has turned Crimea into a territory of fear and insecurity, a huge military base, and a place of systematic human rights violations. Unfortunately, illegal searches and detentions have become commonplace. On March 5, a wave of massive illegal searches took place in occupied Bakhchisarai and the Dzhankoi district in the homes of Crimean Tatars: Crimean Solidarity activists and religious leaders,” said Tamila Tasheva, the Permanent Representative of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

***

“Until 2015, my husband brought Ukrainian literature to Crimea and opened a library,” recalls Elzara Shukurdzhyieva. “Whenever he came home, the FSB officers waited for him on a bench. Before each event, they would take a receipt that he could be arrested. He would sign it and go out anyway. He was arrested for unfurling the Ukrainian flag. One day, when he was going to Crimea, he was detained for a long time. They said: ‘Don't come here again. If you come here again, they won't find you anymore.’ He realized that the games were over.”

The material was prepared with the support of the Mediamerezha.

Author: Olha Hembyk

- Share: