He released Kherson, wrote the script for his funeral and determined the places where the ashes would be scattered. In memory of Danylo Boguslavskyi

Shortly after the liberation, the ashes of Danylo Boguslavskyi were scattered over Kherson. He died in mid—October during a counterattack on the city. Since Kherson was liberated thanks to him — but, unfortunately, without him, the brother and friend left a part of the fighter in the city for which he gave his life, and fulfilled Danylo's last wish — he wrote a script for his funeral and ordered what to do with his ashes.

Using only present tense when talking about the deceased

In his native Uzhhorod, people still do not speak of Boguslavskyi in the past tense. “I feel like he's around, I just can't call him,” was the phrase used by all the people I spoke to. They don't want him to be forgotten. That's why the street where Danylo's parents live will be named after him. And a memorial plaque will appear on the wall of the school where he studied.

A movie about Bohuslavskyi was shown in prime time on the main US sports channel, before the Super Bowl, which is watched by hundreds of millions of people. Later, his brother and colleagues traveled to the United States to tell the world once again about a Ukrainian athlete who played American football but put on a bulletproof vest instead of shoulder pads and uniform and defended his country.

On February 25, the Lumberjacks team, where Danylo was a player, is playing a tournament in Uzhhorod in memory of Boguslavskyi. They have already developed a model of the uniforms that will bear the inscription “The Light is for Us”. That's what Danylo said when he explained his motive for going to this war.

“When I asked my brother not to join the army, he had already volunteered”

Danylo's brother Roman Boguslavskyi starts the conversation with a movie about his brother. Imagine, he says, on Christmas Eve, the NFL Network, with an audience of 70 million, showing a movie about the athletes of the Ukrainian League of American Football who went to war and died.

“Americans have a tradition of watching football at Christmas, so it's very cool to see the stories of players from Uzhhorod Lumberjacks or Kyiv Patriots told to such a wide audience. By the way, this movie was nominated for Sports Emmy Awards,” says Roman Boguslavskyi.

He is quiet for a moment, and then I hear a phrase that will be voiced by three of the four other people I talked to about Danylo. “I keep talking to him every day, but right now he can't answer me.”

Roman admits that he still reads his brother's messages from the beginning of the great war. Back then, he volunteered to join the territorial defense and asked Danylo to stay home to cover the rear and his parents. “Brother, what are you talking about?” Danylo replied and told him that he had gone to the military enlistment office three days ago and had already been recruited into a guard company.

“He said that he didn't want me to fight because I had a small child and a pregnant wife. He had every opportunity to stay in the rear, but he wanted to be in the front lines. He went to the training ground. He asked to join an assault force and went to liberate Kherson. They walked 35 kilometers from Apostolove, Biliaivka to Nova Kamyanka. The day before he was killed, we talked to Danik (short for Danylo – ed.) for a long time, about 20-25 minutes. It was hard, but he remained cheerful. Everything is fine, he said, the moskals are running away, it's cool. The next morning, I got a call from Danik's friend. The connection was bad, but Volodia was crying into the phone, and I understood everything right away,” Danylo’s brother recalls.

“He knew why he went to war from the beginning to the end”

His friend Volodymyr Feskov was the first to learn of Danylo's death. The day before, they had spoken on the phone, and Danylo, as always, convinced him that everything was fine.

“I remember that day. Sunday, beautiful weather, the sun was shining. I also thought: it's such a beautiful day, I wish nothing could spoil it. And then I got this message, and then Roma (Danylo Boguslavskyi's brother — ed.) and I spent the whole day calling all our friends at the front and beyond, trying to deny or confirm the fact of Danylo's death. Until a field medic said that he was gone, because he had pronounced him dead,” Feskov recalls.

He emphasizes that Danylo could have avoided participating in the war, but he went voluntarily.

“He understood all the risks. He understood the main mission. It was not an unconscious act, without a reason. He could list all the people he went to the war to defend — his parents, his girlfriend, his brother, his brother’s wife and children, all of us... Danylo is the case of a man who knew why he was going to war from the beginning to the end. He had been on the defensive line near the border with Belarus for a long time, and he was terribly angry with all the trenching and making defensive lines. And when he received a combat order for Kherson, he said in a telephone conversation: ‘This is it, now I feel I can contribute to this war.’ He went to this Kherson campaign. And he died,” Volodia says.

When Kherson was liberated, Volodymyr had tears in his eyes: his friend Danik was supposed to be among those greeted with hugs by the locals! But instead, Feskov and the elder Boguslavskyi went to the place of death and found the trench. They scattered Danylo's ashes near the monument to the first sailors, to the sound of enemy mortars.

“The embankment was shelled, but it was not scary. It was scary to say goodbye. I never had a brother. Danik was like one for me. He took care of me, and I took care of him,” Volodia says.

They dreamed of getting together in their old age, turning on Depeche Mode vinyl on a mountain slope, drinking whiskey, and having their grandchildren roll a joint next to them.

“F*cking Black box”

At Danylo's funeral, his family and friends read a letter he wrote during his lifetime. He had willed that his boss, Nadiia Semen, do it. “That letter was structured in a way that only Danylo could do. It was called a ‘F*cking black box’”.

Nadiia Semen quotes a part of the letter: “Hello, everyone, this is the last time. It's not easy for me to write this, but it's probably even harder for you to listen to it now (...) I'm sorry, everyone. I was careless or overconfident, maybe it was fate — I don't know. But I don't regret anything. I had time to be happy, I had time to see the world a little, to experience thousands of different stories, and to create a million different memories together with you. Don't forget what we fought and died for. Glory to Ukraine!”

Nadiia says that Danylo has written down who should do what.

“‘First, I want to be cremated. Secondly, I don't want my funeral to turn into a show, so there should be no politicians, parties, or priests there.’ He also asked that his parents and the girl he had been looking for and loved for a long time be informed of his death very carefully. In short, he planned his funeral as an event, with roles for everyone...

This was Danik's whole personality, he was like that during his lifetime — he constantly made sure that everything was decent and everyone felt comfortable. There were a lot of people at his funeral, up to two thousand. Relatives, friends, all of our employees, the entire rugby team, those with whom he repaired cars in his garage (he used to repair cars at night, he was only 32, and it could have turned into a good business if he had lived)… Going to the funeral, we realized that everything had to be beautiful. We even chose the perfect flowers for him,” the woman recalls.

She remembers that Danylo died on Sunday, October 16, and the last time she spoke to him was on Thursday. “I packed some things, I wanted to give them to him, I asked him how to deliver them: ‘You're not at zero, are you?’ ‘No, we've been at zero for a long time,’ Danik replied. He joked that there was coffee and sweets left in his trunk, and now he is looking for coffee in the captured Russian trenches like a drug addict.”

Danylo willed that some of his ashes are buried and some scattered in special places. He was going to cross the Bosphorus with his friends, so he asked them to pour his ashes into the waters of the strait when they crossed it. In the spring, when the war broke out, he and his family lost their tickets to Tenerife, and he willed that after the victory his relatives fly there and take a piece of his ashes. His parents were supposed to bury some of them under a tree in their house — he used to go there on weekends to help them build it.

Danylo Boguslavskyi’s Scholarship

After Danylo's death, Nadiia Semen and her colleagues thought about what they could do for his parents. They raised money and Nadiia brought it to them.

“Of course, they immediately said, 'Give it to the army.’ I convinced them to keep the money. I said that if he lived, worked, and earned, he could support his parents with this money. If you need surgery in your old age, you can have it done with this money and feel that it was your son who supported you,” says Nadiia.

Soon, Danylo's parents were invited to the office where he worked. They wanted to show them a part of their son's life that they hadn't seen.

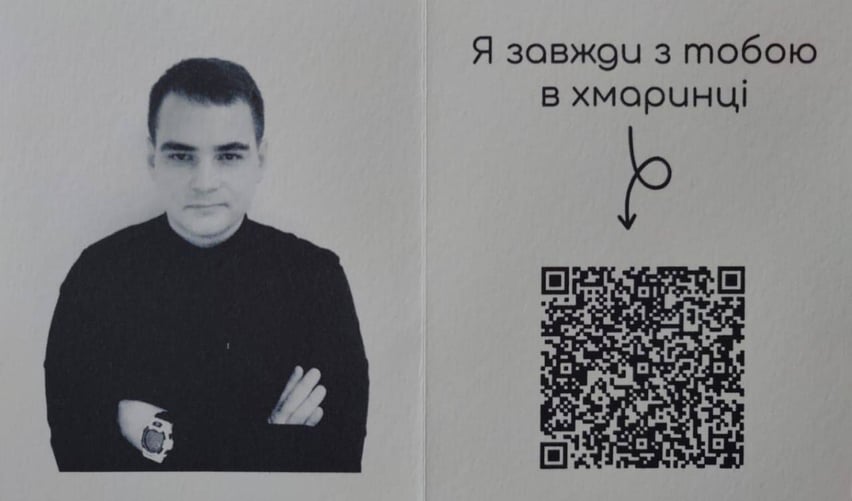

“I sent his mom the voice messages that Danylo sent, the jokes we shared in chats, photos, videos. In the first Covid-19 year, when everyone was afraid of the virus and stayed at home, he drove around the city and filmed cherry blossoms for us... We made a repository with all this, designed it as a photo album ‘Now I'm on a cloud’ with access via QR code.”

The company where Danylo Boguslavskyi worked established a scholarship in his name at UCU. The winner will get a year of study at the Faculty of Applied Sciences paid up. Nadiia Semen says that UCU has a practice where scholarship recipients write letters of thanks to their sponsors.

“We are waiting for Danylo's parents to receive this letter one day. They will be pleased. It will be another moment in their lives when they will be proud of their son again,” says Nadiia.

Author: Tetiana Kohutych, Ukrinform correspondent for hromadske

- Share: