Meet the Cadet Who Sang Ukraine’s Anthem in Crimea During Annexation

Of the 20,000 security officials in Crimea, only 6,000 returned to mainland Ukraine after annexation. Among them were 200 cadets from the Nakhimov Naval School. In March 2014, when the institution was transitioning to Russian jurisdiction, about two dozen cadets sang Ukraine’s national anthem – they immediately became symbols of loyalty to Ukraine.

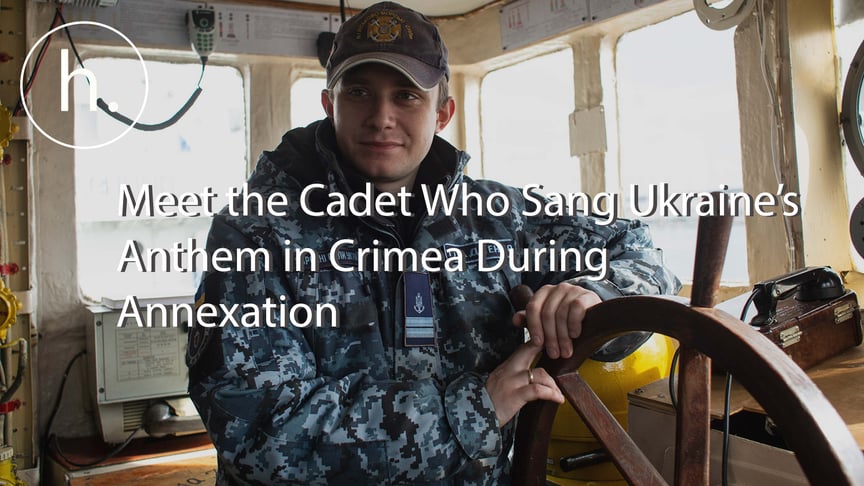

During the annexation of the Crimea, most of the Ukrainian servicemen and law enforcement officers serving there joined the Russian ranks and remained on the peninsula. Of the 20,000 security officials, only 6,000 returned to mainland Ukraine. Among them were 200 cadets from the Nakhimov Naval School. In March 2014, when the institution was transitioning to Russian jurisdiction, about two dozen cadets sang Ukraine’s national anthem – they immediately became symbols of loyalty to Ukraine. Hromadske brings you the story of one of them – Pavlo Hladchenko.

On March 20, 2014, Pavlo, a second-year cadet at Sevastopol’s Nakhimov Academy did not join the ceremonial formation. The 19-year-old, together with several dozens other cadets, remained in the building and watched what was happening on the parade ground out the window. Two days prior, Crimea had been annexed by Russia. The school changed flags and came under new leadership.

When the Russian and St Andrew's flags were hoisted onto the flagpoles, Pavlo, along with his fellow students, ran out of the building to the courtyard and began to sing the national anthem of Ukraine. They quickly got the attention of television crews, who immediately ran up to them. Ceremonial music was then turned up to drown out the singing of the cadets. After finishing the anthem, the cadets saluted, patted each other on the shoulder and returned inside. A month later they came to Odesa.

READ MORE: The True Cost Of Remaining Ukrainian in Crimea

We are sitting with Senior Lieutenant Pavlo Hladchenko in the cabin of the anti-sabotage boat “Hola Prystan,” which he commands, and watching the video taken that day. Pavlo stands in the first row, so he is more visible than others. The now 24-year-old Pavlo has barely changed from his days as a cadet – he still has a boyish face and a slightly shy smile. He occasionally comments on the video; when a cadet takes down the Ukrainian flag, he says: “He doesn’t understand what he is doing. I think he cries there anyway.” When the footage becomes shaky – the cameraman evidently started running toward the cadets – Pavlo laughs: "I thought they were running to beat us up then."

Around two dozen cadets sing Ukraine’s national anthem Nakhimov Naval School in March 2014 as Russia was annexing Crimea.

How does he feel watching this again? He smiles shyly.

“It’s all coming back to me. I'm angry in a way. At their people. That’s not how this conflict should have been solved.”

Commander of the boat Hola Prystan, Pavlo Hladchenko, watches the video of cadets singing the Ukrainian anthem in Crimea during 2014, Odesa, Ukraine. March 1, 2019. Photo: Anastasia Vlasova/Hromadske

Memorabilia from participation in naval exercises, particularly the Ukrainian-U.S. Sea Breeze 2016 exercise. Photo: Anastasia Vlasova/Hromadske

First Visit

Pavlo visited Crimea for the first time in 2009. Back then he was a cadet at the Kyiv Military Lyceum named after Ivan Bohun. As a boy, growing up in a village in the Zhytomyr region, he wanted to be a soldier – although nobody in his family had served in the military. Pavlo says that he was fond of the history of the Second World War, watched war films – perhaps this had shaped his desire to pursue a military career. It was later in the lyceum that he decided to become a sailor.

“I had a friend, Kostya, he always wanted to become a pilot, and I, a sailor,” Pavlo says. “We often dreamed that he would be flying a fighter plane – he’d land on an aircraft carrier and ask: Who is the commander here? And they’d say to him: Pavlo Hladchenko. Well, that’s how it pretty much happened, more or less. Only he flies in a helicopter, and I am the commander of a boat.”

Pavlo Hladchenko on the deck of the boat Hola Prystan, which he now commands, Odesa, Ukraine. March 1, 2019. Anastasia Vlasova/Hromadske

Crew members of the boat Hola Prystan during morning formation, Odesa, Ukraine. March 1, 2019. Photo: Anastasia Vlasova/Hromadske.

Crimea seemed unfriendly to him. Lyceum students went on excursions in military uniform. Pavlo says local residents would give them disapproving looks. He recalls that one elderly woman, seeing a trident on his cap, became outraged. In 2013, Pavlo entered the Nakhimov Naval School. Even then, Crimea remained somewhat hostile for him – again, the problem was in the Ukrainian military uniform. “The locals looked at this uniform with a sort of disgust,” he says.

The military was a common sight in Sevastopol – although more Russian than Ukrainian. The main headquarters of the Russian Black Sea Fleet have been based here since 1997. In 1997, Russia and Ukraine signed a 20-year agreement, and in 2010 they extended it by another 25 years. The only all-Ukrainian population census conducted in 2001 showed that 70% of Sevastopol residents considered themselves “Russian”. When the annexation began in Crimea, Pavlo at first didn’t understand what was happening in the city: “I saw cars driving around with these [Russian] flags. When we walked through Sevastopol and saw tricolors, we didn’t run amok because we knew that these were Soviets. And here I see, people fanatically speeding down the street, whistling, waving flags, shouting: 'Hurray, Russia!'. I thought then – maybe it’s some Russian holiday?”

Communication boat “Pivdenny” on the Ukrainian Navy base in Odesa, Ukraine. March 1, 2019. Anastasia Vlasova/Hromadske

That evening, looking at that day’s news, Pavlo learned that pro-Russian people had gathered on Nakhimov Square, calling for help from Russian President Vladimir Putin. It started to sink in then, he recalls.

It was February 23, 2014. In Kyiv, the deputy of the Batkivshchyna political party (Fatherland), Oleksandr Turchynov, became acting president of Ukraine. The day before it became known that President Viktor Yanukovych had fled the country amid Euromaidan protests. According to Ukraine’s constitution, in such situations the head of parliament would be responsible for taking over the president’s duties. But the speaker of the Verkhovna Rada, Volodymyr Rybak resigned. Thus, deputies appointed Turchynov.

The largest and most noticeable ship on the Ukrainian Navy base in Odesa is the multi-purpose frigate “Hetman Sahaidachny”, March 1, 2019. Anastasia Vlasova/Hromadske

But in Crimea, they didn’t agree with this. In Sevastopol local deputies condemned the “seizure of power in Kyiv”. Up to 25,000 people converged on Nakhimov Square, where they spontaneously selected Aleksei Chaly, a local businessman and a Russian citizen, to be mayor. Then-mayor, Volodymyr Yatsuba, was booed when he called for Crimea to be united with Ukraine. He resigned the following day.

“We were sitting in a double lesson, it was [February 24, Monday]. And then we get an alert – warning, increase combat readiness,” Pavlo recalls how the “Crimean Spring” reached the school. “They gave us body armor – old and ragged; helmets – like a cauldron; handed us automatic rifles and stationed us at different posts. They said one thing: if you notice movement, or a violation of charter requirements – do not open fire to kill.”

At Their Posts

Cadets stood at their posts the entire “Crimean Spring”, from February 24 to March 16. During this time things were changing daily on the peninsula. On February 27, Russian servicemen appeared in Crimea wearing unmarked uniforms – they were called "green men." They blocked Ukrainian military units, but didn’t use weapons – so the pro-Russian activists and the Russian propaganda media outlets called them "polite people". This expression was also echoed by Putin, who called them "forces of local self-defense." Only after the annexation, did the Russian president acknowledge that the Russian military was present on the peninsula.

READ MORE: Separated: Life for Family Members of Political Prisoners From Crimea

The academy was also blockaded by Russian ships from the sea and by armored trucks on land. The cadets, meanwhile, were hoping for all this to be over soon.

“They thought: soon we’ll be dismissed, we will get to go out into the city, some wanted to see their girlfriends,” says Pavlo. “Nobody thought it would end the way it did. They thought – maybe this will go on for a couple of months maximum and then everything will go back to the way it was.”

Pavlo Hladchenko as a second-year cadet at the Sevastopol Nakhimov Academy in the spring of 2014 in Crimea. Photo supplied by Pavlo Hladchenko

The “referendum”, which sealed Crimea’s annexation, was held on March 16. If at first the self-proclaimed authorities spoke of a “special status” within Ukraine, then they quickly changed their plans and set a vote on joining the Russian Federation. After the “referendum”, the school began to persuade the cadets to stay on the peninsula. According to Pavlo, Russian generals and parents of Crimean cadets would visit them. They spoke with them for a long time, urging them to stay at the school. Pavlo says they promised a scholarship of $800 – at the time the cadets received 208 hryvnia ($26 according to the 2014 exchange rate).

“The commander summoned me to his office. He had a map of Ukraine hanging on his wall. He traced around the territory of Ukraine and said: Pavlo, you don’t understand. This will all be gone. Then he traced a circle around Crimea: This is the main thing. I said: No. I’m going home.”

Commander of the boat Hola Prystan, Pavlo Hladchenko, at the command post, Odesa, March 1, 2019. Photo: Anastasia Vlasova/Hromadske

For the first time arguments broke out among cadets. Some said they would go to mainland Ukraine, others said they would remain. Most Crimeans decided to stay. But there were more than a few cadets from other Ukrainian cities who also wanted to stay. Some Lviv cadets, who didn’t speak Russian well, took interest in the proposal. The motivation was simple: For this much money, they could learn Russian.

“I had a friend from the Lyceum – he’s from just outside of Kyiv,” says Pavlo. “He decided to stay. I said to him: Lyosha, what are you doing? Let's go, your mother is there, Ukraine is there, you need to come back. He said: No, I’m going to stay, the salaries are big here and I can help my mother.”

Pavlo says he no longer speaks with him. “This is no longer a friend – this is an enemy of Ukraine.”

Hymn and Honor

After the “referendum”, the cadets at the Nakhimov Academy were able to leave their posts and return to their studies. On March 20, leadership changed at the school. Those who decided to return to mainland Ukraine were told to stay in the crew’s quarters. Most went to join the ceremonial formation. As the Ukrainian anthem played, the cadets removed the flags. When the tricolor and the St. Andrew’s flag were being hoisted up the flagpoles to the sound of the Russian anthem, Pavlo and others ran out to sing the Ukrainian anthem.

"We sang and then went back to the crew’s quarters and sat down," recalls Pavlo. "The commander came and began to scold us: What have you done, what kind of behavior is this. One of the guys then said: You are not our commander anymore, we will not listen to you."

There were two weeks left before they were to move back to the mainland. And there was now the question of where would they live until their departure. Pavlo said that after the leadership change, new – better – produce was brought to the school. “It was all for show,” he says. “Now we couldn’t eat in the same dining room with the Russians (as he calls those who decided to stay in Crimea, - Ed.). They only allowed us to come for breakfast.”

Pavlo Hladchenko in Odesa, March 2, 2019. Anastasia Vlasova/Hromadske

A week later, the cadets were told to leave the school altogether: "Saturday morning, a Russian officer comes in and shouts: Ukrainian cadets must leave the territory of the academy because some kind of general or admiral is coming."

The guys pulled some money together, rented an apartment in Sevastopol and lived there. The academy’s new leadership allocated a small parade ground for them, obliged them to come in every morning and check in, and allowed them to raise their flag.

“They had some kind of officer’s honor after all,” Pavlo recalls.

They barely spoke with the other cadets who “became Russian”. When the school was expecting a visit from important generals, one of the cadets asked Pavlo for black thread – to hem his uniform.

Pavlo Hladchenko with his wife Yulia and son Misha, Odesa, March 2, 2019. Anastasia Vlasova/Hromadske

“I said find your own thread. This one is mine. I didn’t give him anything,” Pavlo says, stubbornness in his voice. Five years later, he doesn’t consider this an act of boyish stupidity.

The Commander

The boat commanded by Pavlo seldom goes out to sea – about once a month and not for combat missions. But he is still satisfied. He says that he’s always wanted to be a commander of a ship, so when he was offered this position almost immediately after graduation, he didn’t hesitate accepting it.

Pavlo was already studying in Odesa. On April 4, 200 cadets from the Nakhimov Academy left Crimea. They warmly farewelled their former comrades – shook hands, embraced. But Pavlo never made peace with what happened – he says that he wants to meet with these people at sea "in order to resolve all conflicts there." He hasn’t spoken to any of his classmates since 2014 and doesn’t know what’s happening with them now.

Pavlo Hladchenko with his wife Yulia and son Misha, Odesa, March 2, 2019. Anastasia Vlasova/Hromadske

In Odesa, the cadets were first assigned to a military academy, which specializes more in land-based professions. After that, they were relocated to the National Maritime Academy. Few teachers and cadets came from Crimea – it was difficult to adjust. In April, pro-Russian meetings were organized in Odesa – they ended in a fire at the House of Trade Unions on May 2. But Pavlo says that he was much more comfortable there than in Crimea. He didn’t think the Crimea scenario would repeat itself in Odesa.

Pavlo’s wife Yulia is from Odesa. She wasn’t so calm about the situation. After the annexation, she feared that everything could repeat itself in Odesa. She says she started to feel safe only after she met Pavlo.

“It was Navy Day, [Ukrainian singer] Alyona Vinnytska came here for the concert,” he says, recalling the day he met Yulia. “An officer gave me a bouquet of flowers and said – give it to her when she comes out. But I saw a beautiful girl, I couldn’t resist and gave the bouquet to her instead.”

The crew of the boat Hola Prystan on the deck at Ukrainian Navy base in Odesa, March 1, 2019. Anastasia Vlasova/Hromadske

Yulia didn’t realize at first that Pavlo was one of the cadets whom she often saw on TV. She says that she followed the developments in Crimea and remembered the story of the Nakhimov cadets who sang Ukraine’s national anthem. She and Pavlo began to talk and married two years later. Yulia says that “everything somehow worked itself out,” Pavlo, that “this was his thought-out strategy.” They have an 18 month-old son, Misha. When he’s older, Pavlo plans to take him to the military lyceum in Kyiv and walk the corridors with him. He’s sure that one day he will also walk the halls of Nakhimov Academy – after having shown his son the video of cadets singing the Ukrainian anthem.

"I’m not a hero"

The Hola Prystan is an old boat, even by Ukrainian standards. It’s more than 30 years old. When inviting us on the boat, Pavlo sheepishly says several times: “Don’t expect anything, we have an old boat”. Then he proudly adds that the crew has looked after this boat well and it’s still in excellent condition. He asks not to photograph the rusty part and explains that the sea water quickly eats away at the paint and the crew hasn’t had time to paint over it. Pavlo speaks about his first ship, almost like his first love.

Labrador Koba is a favorite among the Hola Prystan crew and all sailors at the navy base, Odesa, March 1, 2019. Anastasia Vlasova/Hromadske

The commander is greeted by a labrador named Koba – loved not only by the crew of the Hola Prystan but generally by all the sailors. Koba has lived on the boat for the past six months, since the death of his owner – a friend of Pavlo’s who asked him to take the dog. “He is our sworn brother and mascot,” says Pavlo, scratching Koba behind the ear. The dog closes his eyes, and when Pavlo removes his hand, he pokes at it with his head, asking for more.

“Since Koba appeared, the crew’s morale has significantly improved. And I needed a friend like him.”

The crew of Hola Prystan completes an exercise, Odesa, March 1, 2019. Anastasia Vlasova/Hromadske

The crew of Hola Prystan completes an exercise, Odesa, March 1, 2019. Anastasia Vlasova/Hromadske

Most of the Nakhimov cadets who have left annexed Crimea work here, at the Odesa Naval Base. One of them – commander of the boat "Nikopol" Bogdan Nebylitsa - was captured last November when Russian sailors seized Ukrainian ships in the Kerch Strait. Rewatching the video of the anthem, Pavlo points to one of the singers several times: "This is Bodya (Bogdan), Bodya Nebylitsa." Passing the boats docked near the Hola Prystan he explains: “These are new boats – 2016 make. Bogdan Nebylitsa commanded one of them.” Former cadets have continued their friendship here.

“Many people consider you heroes. How do you feel?”

“For me, hero is a very high rank. We are not heroes,” Pavlo becomes silent and then continues in more solemn tone. “We will show them what the Ukrainian Armed Forces are capable of.”

Koba the labrador is always with the captain and often ties to “participate” in the team training. Anastasia Vlasova/Hromadske

Were his expectations fulfilled five years after he sang the anthem?

“Of course, I never thought it would be like this. That there would be a war, that the economic situation would be like this. But when we sang the anthem, it wasn’t youthful exuberance. We just did what we thought was necessary,” Pavlo says.

READ MORE: 5 Years After Crimea Referendum, Was the World’s Response Enough?

/By Yuliana Skibitska, Oleksandr Kokhan and Anastasia Vlasova

/Translated by Natalie Vikhrov

- Share: