Photographer Documents Disappearing Soviet Mosaics in Ukraine

Ukrainian photographer travelled around the country for three years in search of mosaics from the 1950s to 1980s, the period of Soviet modernism.

Photographer Yevhen Nikiforov travelled around Ukraine for three years in search of mosaics from the 1950s to 1980s, the period of Soviet modernism. During this time he visited 109 towns and villages, where he found more than 1000 works. Some of them have already disappeared from public space as a result of Ukraine's so-called decommunization.

Photographer Yevhen Nikiforov. Photo: Oleksandr Nazarov, Hromadske

Ukraine began the official decommunization process in April 2015, with legislation outlawing communist and Soviet symbols.

The results of Yevhen's search were published in a book titled, "Decommunized: Ukrainian Soviet Mosaics", a joint project of the Ukrainian publishing house Osnovy and Germany's DOM Publishers.

Hromadske spoke to photographer Yevhen Nikiforov and his publisher, architect Philipp Meuser, about finding the art works, mosaic art and the perception of art from the Soviet period.

The founder of German publishing agency DOM Philipp Meuser. Photo: Oleksandr Nazarov, Hromadske

Yevhen began photographing monumental mosaics in Kyiv in 2013, as part of a project on 1960s Ukrainian Art. He became interested in finding other monumental mosaics and created a small archive. The collection of photographs grew as he became more interested in the history of the mosaics and artists who worked on them.

During his travels Yevhen photographed around 1000 mosaics, but the book only includes 200 of them.

Before heading out in search of the mosaics, Yevhen used Google Street View to determine their exact locations. He also used social networks to contact local residents and ask if the works of art are still in place.

Presentation of the book "Decommunized: Ukrainian Soviet Mosaics". Photo: Oleksandr Nazarov, Hromadske

According to Yevhen, the mosaics are usually connected to an address but the street names have often been changed. "Take 10 Lenin Street. Today this street is almost never called Lenin Street," he explained. "I determined the exact coordinates because, a factory, for example, can have one address but kilometres and kilometres of territory. It's important to find the art work's location up to the metre."

Yevhen insisted that the best works in Kyiv are the six consecutive mosaics on Peremohy Avenue. The two central ones were made in the late 1960s. "I came to this place six times to catch the right light and to find the right roof from which to take the perfect shot," he told Hromadske.

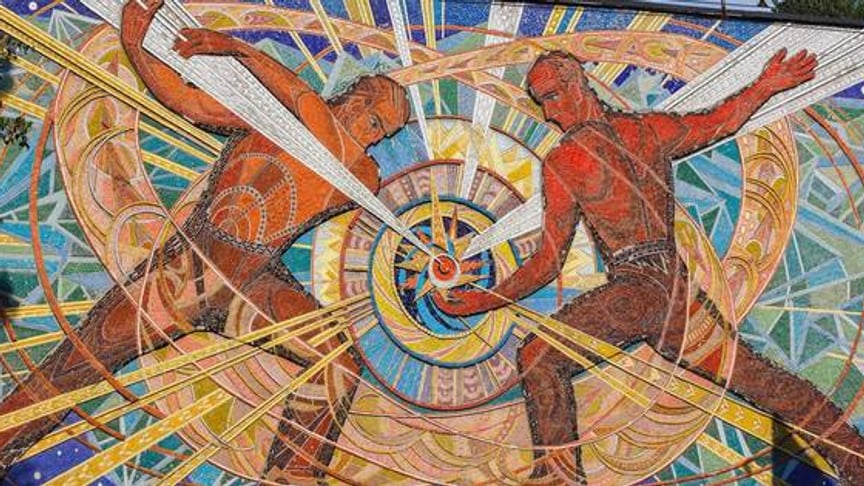

There are also remarkable mosaics at the Institute for Nuclear Research on Nauky Avenue. "If you look at them from a distance of one metre, it's impressive," he said. "You look at these works completely differently and no longer question if this art is art."

Mosaics at the Institute for Nuclear Research on Nauky Avenue, Kyiv. Photo by Yevhen Nikiforov

Yevhen's publisher, Philipp Meuser, was particularly struck by the mosaics in Prypyat, a ghost town in northern Ukraine, where the Chornobyl disaster happened in 1986. "For me this is an example of how art was inscribed in the everyday architecture of the Soviet Union," he told Hromadske.

The mosaics in Prypyat, Ukraine. Photo by Yevhen Nikiforov

When working on the project, Yevhen sought to reveal the mosaics' artistic value. "I tried to do high quality documentation of these art works so that people will pay attention and be interested in protecting them," he said.

Railway station in Mariupol, eastern Ukraine. Photo by Yevhen Nikiforov

Meuser also pointed to the importance of preserving these artworks as part of the long history of mosaics in Ukrainian culture.

South Ukraine Nuclear Power Plant. Photo by Yevhen Nikiforov

"When we consider the mosaic, it is worth remembering that it was not invented by the Communists," he explained. "The tradition of mosaics in Ukraine is nearly two thousand years old and is heavily influenced by Byzantine architecture. They experienced a revival in the '60s and '70s during the period of Soviet modernism. They shouldn't be erased from Ukrainian identity today."

A shop in Ivano-Frankivsk, western Ukraine. Photo by Yevhen Nikiforov

/Reporting by Oksana Horodivska, Oleksandr Nazarov & Yulianna Slipchenko

/Text by Eilish Hart

- Share: