“Their city is shelled but they come here for a tour.” Story of the museum in Baturyn that survived Russian fire and continues to function

Baturyn in the Chernihiv region greets you with silence and bright sunshine. Only near the citadel of the former Cossack fortress can you see lively traffic: children jumping into a white minibus with Sumy license plates, having just finished a tour.

“They came from Shostka, which is often shelled, but they come to us,” explains Liubov Kiiashko, deputy director of the Hetman's Capital reserve. In half an hour, this tour group will be replaced by another one.

Nowadays, just over 2,000 people live in Baturyn, and the city itself looks more like a village, but in the 17th and 18th centuries it was the hetman's capital with a population of over 10,000 people. Until Russia came here. It is a little more than a hundred kilometers away.

When the Great Northern War between the Tsardom of Moscow and Sweden broke out, the then Hetman Ivan Mazepa and his Cossacks initially fought on the side of Peter the Great. However, in 1708, he decided to take the side of King Charles XII, because Peter refused to defend Ukrainian lands.

When Peter I learned about this, he ordered Baturyn to be wiped off the map and all its inhabitants to be killed in revenge. According to various estimates, the Muscovites killed up to 15,000 people here, including those Cossacks who defended the capital to the last.

Several decades later, the city was resurrected by another hetman, Kyrylo Razumovskyi, who was destined to become the last leader of the medieval Cossack state. He again made Baturyn the capital, and in his later years built a large palace and the Resurrection Church, where he was buried after his death.

After the death of the last hetman in 1803, Kyrylo's son Andrii moved into the palace. He owned the palace until his death in 1836, but 10 years earlier the castle had survived a large-scale fire that caused enormous damage. After Andrii Rozumovskyi's death, the palace turned into a wasteland, and Baturyn itself remained an ordinary provincial town.

Kyrylo Razumovskyi's caring descendants sought to revive the palace. One of them was his great-grandson Kamil, who, living in Austria-Hungary, allocated funds for the restoration of the palace so that a Museum of Folk Art could be created there. But this was not to be due to the maelstrom of World War I, and later the revolution of 1917-1921. And in 1924, a large fire shook the palace again.

Other monuments of the Cossack era also suffered, but at the hands of the Communists. In 1927, the head of the Konotop Museum of Local Lore, Oleh Poplavskyi, came to Baturyn with an expeditionary group and ordered the opening of the crypt where Razumovskyi's body was buried. From there, they stole the heart of the last hetman and hid it, and it is still unknown where it is now.

The restoration of the memory of the former hetman's capital began in the first years of independence. In 1993, a reserve of the same name was created here, which was housed in one building, the General Court House (also known as the house of Vasyl Kochubey, the General Judge during the Hetmanate of Ivan Mazepa).

And in 2008, on the 300th anniversary of the Baturyn tragedy, the citadel of the destroyed fortress was rebuilt under the program of Viktor Yushchenko, and the reserve was granted national status. For this, grateful Baturyn residents named a lane leading to the reserve in honor of the fourth president of Ukraine.

“We were spared the occupation, but we heard everything and still do”

In 2022, when Russian columns were advancing on Kyiv through the Chernihiv region, the former Cossack capital was constantly shaken by explosions, but did not fall under enemy control.

Nowadays, the sounds of Russian missiles and aerial bombs can be heard from neighboring Konotop and Hlukhiv, but fortunately, Baturyn itself was not affected by the shelling. Recently, the town suffered another disaster: the Russians poisoned the Seim River, and many fish died out in the reservoir. Liubov recalls that the stench could be smelled throughout the city.

In the first days of the Great War, museum workers began to hide the monuments. They put films on the windows, and piled sandbags near historic buildings to protect them from flying debris and fire. Wax figures of Ukrainian hetmans were hidden in the basement.

At the beginning of the full-scale invasion, no one even thought of tourists, but in the summer it became calmer and visitors began to arrive. And in the fall of 2022, the Hetman's Capital equaled the number of guests with the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, which had previously received the most guests — more than 1 million people a year.

“In 2021, despite Covid and all that, we received 177 thousand visitors. The war, of course, had an impact, there is no comparison at all. But last year we received about 70 thousand visitors. And that's not even counting our online exhibitions,” Liubov boasts.

Six employees of the reserve are currently defending the country: researchers, a deputy director, a security guard, and an electrician. All of them went to the front voluntarily.

“We talked about Baturyn all the time, but people did not understand us. Now they do”

Liubov leads us to the Resurrection Church, a small wooden church that stands in the middle of the citadel courtyard. It was rebuilt together with the fortress in 2008, and now church services are held here on major holidays, including the anniversary of the Baturyn tragedy.

Inside, the sun's rays fall on military flags hanging over portraits of fallen soldiers from the Baturyn community. In a moving voice, she says: “These are our heavenly warriors now.”

When the Muscovites approached Baturyn in 1708 and stormed the town, the parents tried to save their children and hid them in the most fortified part of the fortress. Some civilians also hid there. However, when Menshikov's army broke into the city, the Muscovites did not spare anyone and killed everyone who was hiding here, and the church was destroyed.

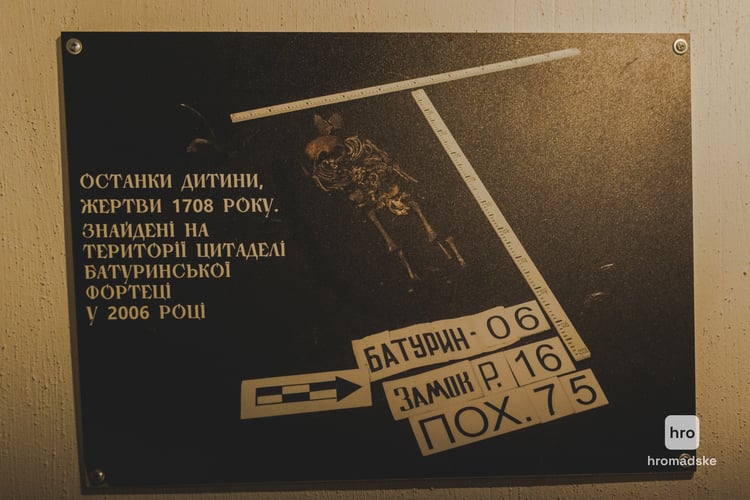

We go down into the crypt of the church, where the remains of the murdered Baturyn residents, including children, are buried. Liubov points to a photo of the remains found during excavations when the fortress was being rebuilt: the remains of a 14-year-old girl who was hiding from a fire in a grain pit. She died of suffocation.

Next to the coffins where the remains of the murdered Baturyn residents are buried, there are portraits of children, and under their photos are two dates — birth and death, the latter dated 2022 and 2023. These are photos of children killed by the Russians after the start of the full-scale invasion. The installation was symbolically named: “Yesterday Baturyn, today Bucha”.

“Many people did not understand much before the full-scale invasion. We talked about the Baturyn tragedy all the time. We talked about all the tragic pages of history. But people did not understand. And when it happened again, many people realized that the enemy remained the same, and its methods remained the same as 300 years ago,” says Liubov.

“We want to find a mace, at least Mazepa's one”

We leave the crypt and go outside. Liubov leads us to a closed room that looks like a village barn. This is an arsenal where Cossack weapons were kept in Hetman's time, and now various military utensils are kept. This installation was opened in May, and some artifacts were also found this year.

Despite the war and the proximity to the Russian border, archaeological excavations continue, with a break in 2022-2023. However, this year's expedition was the smallest ever.

I ask if there is anything they want to find but don't know where it is hidden:

“We want to find the Hetman's mace,” Liubov answers and continues, “We don't know if it's here or not, but we know for sure that there is no Hetman's mace in Ukraine today: neither Khmelnytsky's, nor Mazepa's, nor Samoilovych's. Every exhibit is important to us.”

We do not know where the hetman's maces are now, but we do know that many valuable artifacts were taken from Baturyn (as well as from many other cities) to Russia. The most famous are the Lion cannon that stands in the Kremlin and the Mazepa bell. It was believed to have been destroyed, but in 2015, attentive scholars noticed it in a monastery in Orenburg, Russia.

Next, we go to the Hetman's House of Ivan Mazepa, the Cossack Presidential Office, as Ms. Liubov jokes. It used to be a majestic building, but in 1708 it was destroyed by Menshikov's Moscovite army.

We go inside and find an exhibition of wax figures of hetmans, some of which have already been lifted from the basement where they were stored at the beginning of the full-scale invasion. I recognize them all: Khmelnytsky, Vyhovskyi, Doroshenko, and when I get to Mnohohrishnyi, Liubov corrects me: he is Demian Ihnatovych, not Mnohohrishnyi.

Rumor has it that he received this nickname because of his peasant background, as there were no surnames in the villages. Another version says that he was called Mnohohrishnyi by the Hetman's Treasurer Roman Rakushka-Romanovskyi in his Chronicle of an Eyewitness because of a personal conflict.

In the largest hall there are statues of Pylyp Orlyk and Ivan Mazepa. In the corner, there is a torban, a multi-stringed instrument that looks like a bandura, but its structure and playing are much more complex. Liubov says that there were not many people who wanted to play, but everyone recognized that it was not an easy instrument.

“Which way is Russia?”

As we walk to the main tower of the citadel, I ask Liubov about the current life of the Baturyn people. She tells me that with the outbreak of the Great War, many people left for safer regions. Instead, people from Hlukhiv moved to Baturyn. Liubov Kiiashko says that people don't want to go far from home because they believe they can come back.

It is difficult to climb the tower: the stairs are high and there are many of them. “Here are some exercises for the evening,” Ms. Kiiashko jokes. I ask our guide which way Russia is. She points to the northwest. It was from there that the Muscovites went to burn the city in 1708, and from there they came to capture Chernihiv in 2022.

300 years ago, Baturyn fell for two main reasons: there were already Russians inside the city, and there was a traitor among the locals, Ataman Ivan Nis, who helped Menshikov's army get into the city. Liubov believes that this story will not repeat in Baturyn.

- Share: