A teacher’s war: Volunteering at 57, mourning 15 students lost

“Once, in Zaporizhzhia Oblast, police cars with sirens were transporting the bodies of our fallen soldiers. Dogs gathered and started howling. It was eerie, terrifying,” Oleksandr recounts.

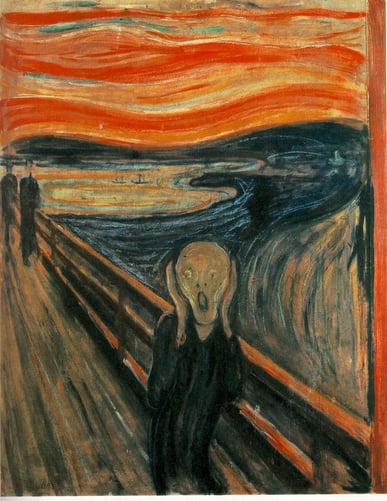

For him, the image of war has long been akin to Edvard Munch’s The Scream—a soul, torn apart by horror and anxiety, crying out to the world for compassion and support.

In 2022, it was crystal clear to Sashko: as a man, he had to go to war. Who else would protect three generations of his family—his wife, children, and grandchildren? At the time, he was 57 and a half. And he went. Now, he wishes no one would ever have to experience war.

In the hospital, for the first time in his life, he felt the urge to paint an icon. To create images of Christ and the Virgin Mary on ammunition crates—to show that, through the evil and horror of war, something holy and merciful can emerge from that which brings death.

We traveled to Oleksandr in Kivertsi, Volyn Oblast—now home after demobilization, where he paints icons. And he teaches physical education and “Defense of Ukraine” at the local lyceum, striving to impress upon young men that even the slightest negligence in war can cost a life. They, too, may one day have to fight…

Kicked out of the army for being too old

When Oleksandr rode with other volunteers to a military unit in a neighboring district center in February 2022, he found himself sitting next to a former student, a veteran of the Anti-Terrorist Operation (ATO). The age gap between them was like that of a father and son, but it didn’t faze him.

“I never doubted my ability to fight, not for a second. I had military experience—I served in the Soviet army—and life experience, too. I could make calm, measured decisions. There was no time for doubts. That student of mine on the bus—he worked as a security guard on an Israeli cruise liner—when the full-scale invasion began, he left that cushy job, came back from the shores of Mexico to defend Ukraine. And I, living in Ukraine, was supposed to hesitate? I remember the mood of the guys on that bus—it was such a high! I’m glad I got to feel that,” Oleksandr recalls.

He ended up in an anti-aircraft missile regiment, serving as a soldier in a mobile fire team. At first, his brothers-in-arms were skeptical—what are these old-timers up to? But the lean, wiry physical education teacher was in excellent shape. His task was to protect Ukrainian anti-aircraft systems from Russian drones. He wasn’t directly on the front line, but he went out daily with his team on alerts, firing at enemy Shahed drones with a rifle or machine gun. He says the service came easily, he wasn’t afraid for himself, only deeply homesick and worried for his family.

In between combat missions, he started drawing. After school, Oleksandr had trained as a woodcarving craftsman, with drawing as a core subject. But then he studied at a pedagogical institute, became a teacher, and set aside woodcarving and drawing for years. On the front, the urge returned.

Sashko says he drew on whatever was at hand: a Swedish notebook from humanitarian aid or scraps of a crossword collection. He didn’t draw himself or his brothers-in-arms but something far removed from the surrounding reality. For instance, a jazz orchestra—filling the page with human figures, mentally recreating the sound of jazz compositions to escape the war.

Then came what he calls “a hundred devils!”—when you go to the commanders about hospitalization for a kidney stone, and they pull your file, suddenly realizing you’ve turned 60. They call you a pensioner and kick you out of the army—for being too old. Never mind that you can do more pull-ups than your 35-year-old brothers-in-arms.

“When I joined the Ukrainian Armed Forces, I didn’t think you could retire from a war. I couldn’t imagine my guys staying in the ranks while I had to go home. That I’d leave the unit because of age, not because the war ended. I wasn’t planning to go home until it was over. But I’m telling you, they forced me out. If a law came out allowing men over 60 to continue serving if they want, I’d go back. Why write off people who can and want to fight?” Oleksandr says, visibly upset.

A mine on the computer and a machine gun under the bed

Oleksandr joined the army as a physical education teacher. When he was discharged last year for his age, the lyceum offered him the chance to teach “Defense of Ukraine” as well. He agreed—there were no other male teachers with modern combat experience. And this subject must be taught well: the war has been raging for 11 years, 15 of Oleksandr’s students have died on the front, and dozens have fought or are fighting. Military preparation starts in school.

We sit with him in the lyceum’s basement, once a student shooting range, now a shelter. We discuss how there’s nowhere for students to practice shooting during military training lessons. Even if there were a range, there’d be nothing to shoot with. He’s had to explain shooting principles using his hands.

Oleksandr had no textbooks for “Defense of Ukraine,” no visual aids, not even charts. At his request, brothers-in-arms sent him body armor, helmets, and a gas mask. One fellow soldier donated his gear, having brought better equipment from England. It’s almost laughable, but not funny at all, that Oleksandr borrowed a rifle and machine gun from historical reenactors for lessons. After class, he kept them at home by his bed as there’s no secure storage room at the lyceum. The reenactors lent the weapons briefly, but at least the kids got to see and hold them.

“I asked volunteers for tourniquets for lessons; my unit sent me a few. I came up with standards for applying tourniquets—some girls cried from the pain when I made them tighten harder. I explained it’s not my whim; it’s about life and death. I bought a dummy mine and grenade at the market, taught the kids to set tripwires and do demining. I’d say, ‘Here’s how you booby-trap your computer, because if Russians break into your house, they’ll go straight for it.’ The kids got creative, brainstormed—it was interesting for them. But I had to figure out this method myself; it took time. This isn’t phys ed, with few words and lots of movement. Here, you have to explain, teach, so the kid at least somewhat masters the mine or machine gun and doesn’t show up to war like a helpless kitten,” Oleksandr says of his teaching.

He mentions plans for a dedicated military training classroom with weapons, tourniquets, and body armor—a great space for practical skills. But he doesn’t know when it’ll happen. He’s aware that today’s military training, especially in rural or small-town schools, leaves much to be desired, as if there’s no war.

He’s also frustrated that phys ed classes, in his view, don’t involve serious physical exertion. “A student should warm up a bit, not sweat hard,” he says with a sad laugh. But future soldiers need strong physical conditioning—on the front, your life often depends on whether you can sprint to a trench or leap off an armored vehicle.

He tries to drive this home to his students. According to Oleksandr, the lyceum students don’t ask much about the war. Maybe because it’s already in their homes and families, as their fathers or older brothers are fighting. But when he tells them to press their heads to the ground while crawling because an enemy bullet might be flying, they listen.

Teaching students to preserve their lives in war is now the only way this former soldier can protect them.

The school year has ended, and Oleksandr is wrestling with whether to continue teaching “Defense of Ukraine” come September 1. On one hand, he’s figured out how to teach it. On the other, he wants to paint more icons. But who else would take the subject? Young specialists earn 8,000 hryvnias ($191)—such pay, even with draft exemptions, won’t lure men to teach. So, Oleksandr weighs the pros and cons—he has until September.

Green box revelations

When he was discharged, he was glad to be alive and returning home. But it was hard to leave his brothers-in-arms. His first icons—Christ and the Virgin Mary—on ammunition crates were painted for his fellow soldiers to decorate their barracks, replacing the cheap Chinese calendars they hung. It was his first time painting with oils.

He says his works aren’t icons for prayer. No one prays to Renaissance depictions of saints—they’re seen as paintings, symbols of eternal purity.

“And I want the same: for something eternal to emerge on crates marked for ammunition, which bring death. Some people paint icons on the inner, unmarked side of the boards. But I’m drawn to the unpolished wooden surface, the numbers and letters of the markings, nail marks, metal hinges, cracks, and breaks. The guys brought me plywood crates at first, but I don’t want plywood—I want battered wooden crates. I don’t know how to explain it, but it holds deep meaning for me,” Oleksandr says.

His workshop is in a room next to the kitchen. Three walls have windows, and there’s even one in the ceiling, letting you gaze into a sky that holds the secrets of the lofty and eternal. Though, the ceiling window is practical—for better lighting. Paints, brushes, a palette, a cot, a woodstove, cream-colored linen curtains on the windows, their elegance starkly contrasting the grenade crates piled in the corner.

He leads us with the photographer to another workshop, where woodworking machines stand, showing us stacks of crates (thanks to volunteers who deliver them)—Ukrainian, NATO, even Soviet-marked, green, red, and black as scorched earth. The photographer and I try to move them—impossible, they’re so heavy, even empty. And yet, soldiers on the front haul them full of shells or mines. My mind spirals: How many divine faces must Oleksandr paint on these crates for God to grant us victory? And what does the Christ he paints know about our war?

I want it to sink in!

On his easel, an unfinished image of the Savior in a crown of thorns. Christ weeps bloody tears, red-black paint streaming into the cracks of a black-green board. It’s as if the war itself scarred the ammunition crate for this.

I ask Oleksandr about inspiration and painting techniques. He says he often paints to jazz music, that the work consumes him. Then, firmly, he adds:

“Please don’t make up that holy faces appear in my imagination. Nothing appears to me. I find ideas for images online. Just ideas—I don’t copy. Back in art school, I studied anatomy and body proportions thoroughly, so creating faces is no issue. The composition depends on the board’s texture and markings. I also find Bible quotes for my icons online. For example, on the first icon for my brothers-in-arms, I wrote: ‘If God is for us, who can be against us?’—Apostle Paul’s letter to the Romans. Very fitting, I think.”

According to Oleksandr, his first icon took three or four days. Now, he works faster, but often paints and repaints until he achieves the effect he wants.

“What effect are you after?” I ask.

“So that when you look at it, it really sinks in,” he replies.

He laments that sometimes he lacks the experience and skill in painting. Right now, he’s struggling to make a face appear through a mist, something he really wants to achieve.

At first, he gave his icons away. Now, soldiers often commission them—he doesn’t take money for this work. They request them for themselves or as gifts for churches, so they must like his painting, which pleases the artist. He hasn’t counted his icons but thinks there are about two dozen.

Oleksandr gives us a tour of his home. This stunning wooden table—he made it himself. The shelving unit and cabinet, adorned with carvings is also his work. And this Cossack, dancing the hopak, spinning the sky and earth in his whirlwind—he carved it himself from oak.

On a wall in one room hang several icons. Compared to those in his workshop, they’re very academic.

“Byzantine canon,” Oleksandr explains. He says his son, who studied sacred art at an art academy, painted them. In the end, he became a computer graphics specialist. Now, he serves as a rifleman in a border guard brigade.

“I didn’t want him to go. He’s an artist—never held anything heavier than a paintbrush. I was afraid he wouldn’t manage. But he’s managing, there since January,” Oleksandr says, his voice a mix of tenderness, worry, and pride.

He also has a daughter and two grandchildren. Oleksandr hopes they’ll never endure what he, their uncle, and their father (Oleksandr’s son-in-law, also fighting) have.

We walk through the schoolyard—a stray dog that’s long attached itself to Oleksandr trots alongside. When Sashko teaches, it waits patiently outside the lyceum or shelter. We take photos at the stadium, and Sashko warmly hugs a young man cutting through the schoolyard.

“He studied at our school, just came back from the war,” Sashko explains later. The war has leveled their roles—no longer teacher and student, but two brothers-in-arms.

***

Finally, we go with Oleksandr to the local church, where in the tough ‘90s, to earn a bit of money, the phys ed teacher made wooden furniture, wall decor, a confessional, an altar, and saint figurines after school. His teacher’s salary was 30 hryvnias ($15), and his daughter cried, asking why there was no meat in the borsch.

“I decorated several churches, made wooden ladders, and did a lot with wood. All my life, I did what people needed to earn money, to raise my kids. For a teacher in a small town, it wasn’t easy. So don’t romanticize me. Only now can I do what I want—paint icons, spend time with friends. On weekends, we hit the gym, go to the market, buy 20 choice farm eggs, fry them up, eat with vodka, play cards for squats—it’s good,” Oleksandr says as we part.

- Share: