Ukraine’s ports in flames: Can exports survive, and will food prices crash?

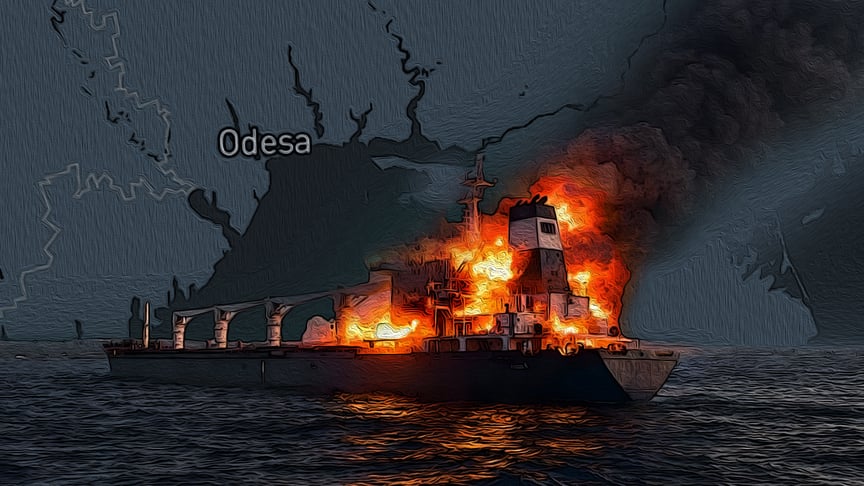

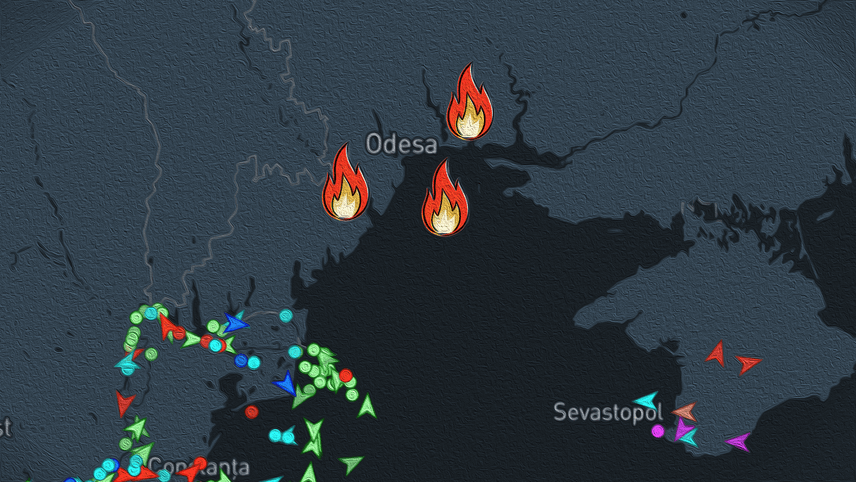

Since late fall 2025, Russia has stepped up attacks on the ports of Odesa Oblast. Russian missiles, drones, and uncrewed surface vessels are also targeting merchant fleet vessels and related infrastructure, including container terminals, grain elevators, oil-processing plant assets, railway hubs, and bridges.

In 2024, 36 Russian attacks were recorded. In 2025, that number has already reached 96, according to the Ukrainian Sea Ports Authority (USPA). The scale of destruction is growing too: since the start of the full-scale war, 651 port infrastructure facilities have been damaged, with 325 of those hits coming in 2025 alone.

“In reality, this is an element of destroying Ukraine’s logistical potential, which triggers a domino effect because our main exports go through the seaports of Odesa. Accordingly, if logistical capacity to support that export shrinks — and we are talking about agricultural products and metallurgical goods — then the ability to sell those products shrinks too. Foreign currency revenue falls, and budget spending gets squeezed,” notes Mykhailo Honchar, president of the Center for Global Studies ‘Strategies XXI’.

The great Black Sea escalation

On November 28, in the Black Sea, two sanctioned tankers carrying Russian oil were struck. According to media reports, this was an SBU operation. On December 10, SBU Sea Baby naval drones hit another tanker in the Black Sea: it flew the flag of Gambia and was also carrying Russian oil.

On December 12, Russians struck the ports of Odesa Oblast with Shahed drones and ballistic missiles. In Chornomorsk port, a Turkish-flagged ferry was damaged, along with a container crane. Another strike hit a similar crane in Odesa port. One employee of a private company — a Ukrainian — was wounded.

On December 19, Russian ballistic missiles struck port infrastructure in Odesa Oblast again. This time, eight people were killed.

On December 30, Russian drones attacked not only the ports of Odesa Oblast but also the Panamanian-flagged cargo ships Emmakris III and Captain Karam, which had entered to load wheat. The ports of Pivdennyi and Chornomorsk suffered the most damage. Following a now-familiar tactic, the Russians launched a follow-up strike the same day. Oil storage tanks caught fire.

“There was an unspoken rule, especially among exporters and importers of hazardous cargo like diesel fuel or oil, not to accumulate more than 10,000 tons in the port. And here they miscalculated: a full batch of 40-50 thousand tons was completely burned. Somehow, the Russians got that information. This means losses for the ports and losses for private business,” says Viktor Dovhan, former deputy minister of infrastructure.

“I spoke, for example, with sunflower oil exporter-processors — the company Allseeds. They suffered quite serious losses; several [tanks] in Pivdennyi port were completely bombed,” Dovhan adds.

In addition to Allseeds’ oil tanks, Kernel’s oil plant in Chornomorsk port was hit. Kernel is one of the world’s largest producers of sunflower oil. “Grain certainly does not burn as well as oil,” Viktor Dovhan explains the logic behind Russian strikes.

On the first day of 2026, Russians struck the berth in Odesa seaport again, as well as Izmail port on the Danube River. On January 7 came another attack. Containers filled with oil were destroyed at the Chornomorsk port, and damage was inflicted on facilities at the Pivdennyi port. The very next day, Russian drones struck Odesa Oblast port infrastructure once more, targeting an oil storage tank — but it turned out to be empty. That same day, the Russians took a hit too: a drone attacked a tanker flying the flag of Palau that was heading toward Russian shores, likely to the port of Novorossiysk.

The Russians did not let up. On January 9, they struck two merchant vessels. One, flying the flag of the Comoros, was carrying soybeans and was near Odesa port. A crew member — a Syrian national — was killed. Another vessel, under the flag of Saint Kitts and Nevis, was en route to Chornomorsk port to load grain.

On January 12, more strikes targeted vessels near Odesa Oblast. One had planned to load oil; the other already carried a cargo of corn. Overall, since fall 2025, the Ministry of Development has recorded at least about 20 attacks on civilian vessels in the area of Ukrainian ports.

“In addition to missiles, uncrewed surface vessels (USVs) and guided Shahed drones — now upgraded to target moving objects, that is, ships — have become a major threat,” notes Iryna Kosse, transport sector expert and leading researcher at the Institute for Economic Research and Policy Consulting.

“This has forced the introduction of stricter security measures. Port and corridor operations are under tight restrictions. Ports close at 8 p.m., and that cutoff is critical for physically sealing the water area with booms to protect against nighttime USV attacks. Even small delays in a vessel’s departure (10-15 minutes) are treated as a serious risk. So a ship that finishes loading in the evening may be forced to wait in port until the next morning, risking becoming a target,” the expert adds.

Particular attention should be paid to USVs, also called “naval drones.” For a long time, Ukraine held an advantage over Russia in this area, acquiring USVs well ahead of the enemy. But the Russians now have their own USVs in addition to their “classics” — Shaheds and various types of missiles.

“Russia lagged behind us seriously for several years, but now it has caught up. The recent hits on vessels that arrived to load in Odesa are proof of that. So in this context, the questions are strengthening air defense and, accordingly, stepping up efforts to neutralize the threat from the enemy’s uncrewed surface vessels,” comments Mykhailo Honchar of the Strategy XXI Center.

“USVs can reach the ports of Greater Odesa in four to six hours, which forces physical closure of the ports at night,” adds economist Iryna Kosse.

The systematic nature of Russian strikes is alarming. First, they are extremely intense and at times resemble a true firestorm. Second, they are quite well planned.

“The complexity of the situation is that earlier, the Russians mainly hit ports and property complexes; now these strikes are systemic. They hit ports and vessels carrying both export and import goods simultaneously. That is new. They hit the region’s energy infrastructure as a whole. Odesa Oblast and its power system are one focus of the strikes. They hit the railway system. We see a lot of strikes on railway hubs in Odesa Oblast, on railway hubs inside the country, and on points where cargo flows form. Clearly, the aggressor state is targeting the systematic destruction of Ukraine’s export and import potential and is taking all actions to achieve that,” says Serhiy Vovk, director of the Center for Transport Strategies.

Notably, Russian strikes on Odesa Oblast ports intensified after mid-October 2025, when Odesa Mayor Hennadiy Trukhanov lost his Ukrainian citizenship. At that time, the SBU discovered he held Russian citizenship. Could the Russian strikes be a form of revenge for Trukhanov?

“I have heard that version, but it is so absurd that only guppies who do not remember what happened yesterday could take it seriously,” says Odesa resident Arkadiy Topov.

Ukraine’s export dependence on ports

The agricultural sector — traditionally export-oriented — suffers the most from the tense situation in the ports of Odesa Oblast and the surrounding Black Sea waters. Due to Russian strikes, only 3.6 million tons of grain, oilseeds, and their processed products were exported through Odesa Oblast ports in December 2025 — 8 percent less than the previous month, according to the Ukrainian Agribusiness Club (UCAB).

“In the absence of attacks, export volumes could have been higher, as Ukraine still has a sufficient supply of export-oriented agricultural products,” says Svitlana Lytvyn, head of the analytical department at the UCAB.

“At the same time, constant attacks cause significant logistical delays and a sharp rise in costs for exporters. Queues of railcars waiting to unload are already being recorded, and damaged infrastructure creates risks of further reductions in shipments over the coming months,” she adds.

Maritime logistics remains the key route for exporting Ukrainian agricultural products. It is cheaper than rail or road transport and more convenient for large volumes. For Ukraine’s strategically important agricultural clients in Africa and Southeast Asia, sea routes are the only viable option.

In 2025, 39.8 million tons of Ukrainian agricultural goods — grains, oilseeds, and their processed products — were exported through ports in Odesa Oblast. Seaports accounted for 87 percent of that export. The rest went by rail (7 percent), via Danube river ports (3 percent), by road transport (2 percent), and via other channels, the UCAB reported.

One striking fact is that Russians are deliberately targeting everything related to Ukrainian sunflower oil: its production and transportation. Together with meals, oil accounts for more than 15 percent of Ukraine’s foreign currency earnings and about 20 percent of commodity exports, according to the Ukroliyaprom association.

“Before the war, we produced more oil than the Russians. Now we have let them pull ahead. This is especially true for the Indian market. The Russians feel very comfortable there and simply want to monopolize it,” explains former deputy infrastructure minister Viktor Dovhan.

“If export opportunities for a certain type of product shrink, domestic market prices automatically drop because traders simply stop buying sunflower or rapeseed for processing into oil, since there is no way to export it. That, in turn, hurts the agricultural sector. It loses part of its income, and the effects pile up. The sector suffers, lacks working capital, cannot buy fertilizers or seed in needed volumes, and cannot plant,” says Serhiy Vovk of the Center for Transport Strategies.

If Ukrainian seaports cannot move agricultural products to foreign markets in required volumes, two main consequences follow. First, less foreign currency enters Ukraine, which could weaken the hryvnia. Second, unexported goods could be redirected to the domestic Ukrainian market, potentially lowering food prices by simply increasing supply.

The Ministry of Defense is a major buyer of food products, paying for troop rations. In an extreme case, the government could have the ministry purchase surplus products from Ukrainian producers. Other state procurement structures could also buy from the market.

“If we recall 2022, export prices first rose because of the Black Sea blockade, then fell once the grain deal started [allowing sea export of Ukrainian goods]. Domestic prices dropped 45 percent in June 2022 compared with January,” economist Iryna Kosse recalls. Still, there has not yet been a mass shift of Ukrainian agricultural goods to the domestic market.

But if large volumes of grain and sunflower oil remain in Ukraine, domestic prices could fall similarly to 2022 levels — more than 40 percent. The same would apply to processed products: bread, flour, and pasta. When supply rises, and demand stays the same, prices naturally drop.

It is not only agricultural exports that suffer. Any export and import shipments are affected because Ukraine’s Black Sea ports now operate under restrictions. “The most tangible indirect factor is downtime due to air raid alerts. Over the past year, more than 800 alerts resulted in total port downtime exceeding one calendar month. That is a colossal blow to business economics and port rhythm,” transport expert Iryna Kosse notes.

Logistics costs are rising because vessel operators now require coverage for war risk insurance. Ships heading to Ukraine today were mostly chartered months ago; the next ones will cost more, according to transport expert Serhiy Vovk.

Container terminals — already few in Ukraine — are suffering from Russian strikes. These terminals handle imported containers with a wide range of goods: from clothing to equipment.

About 25 percent of automotive fuel imports come through Odesa Oblast’s Danube ports. The rest arrives overland via the Polish and Romanian borders. “Even if diesel or gasoline imports through ports stop completely, it is not critical. Maybe Odesa Oblast would feel some temporary interruptions because it consumes more there logistically. But logistics are already so well worked out from Lithuania, Poland, and Romania that there would be no problems at all,” says former deputy infrastructure minister Viktor Dovhan.

Is it realistic to reconfigure Ukrainian export logistics if Russians inflict critical damage on seaports?

“The alternative, as always, is the Danube ports — Reni and Izmail. But Russians are using naval drones on the Danube too, so that route is not completely safe and is also under threat. Speeding up the process — for example, conducting diver inspections of vessels in the Sulina channel — is not possible because that is Romanian territorial waters. Another alternative is export via land border by rail and road, but capacity there is limited too. Ukraine currently has no real alternative to seaports. So the main strategy is protecting and maximizing the efficiency of the existing sea corridor rather than fully reorienting to other routes,” says economist Iryna Kosse.

“Giving up maritime trade essentially means blocking exports. Even under current conditions, 90 percent of exports go by sea. Switching — as was the case in 2022, when much was blocked, and we partially shifted to land routes via western crossings — simply makes Ukrainian exports uncompetitive. Europe’s transport system is extremely expensive for moving the kinds of goods we have — grain or other commodities,” says Serhiy Vovk of the Center for Transport Strategies.

- Share: