Anatomy of ecocide. Why the war will resonate with us for hundreds of years to come

The environment is called a silent victim of war. Sometimes it seems that nothing could be worse than human losses and catastrophic destruction. But it is not without reason that the consequences, which are not obvious at first glance, are compared to a time bomb.

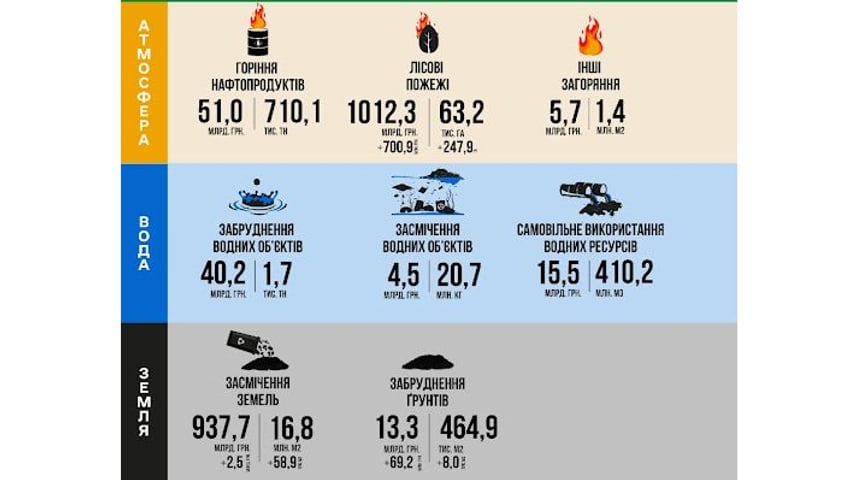

Although we hear the word “ecocide” more and more often, we still do not realize the full extent of this time-long disaster. The damage that the occupiers have caused to our environment and ecosystems is unprecedented and often irreversible. The Ministry of Environment currently estimates them at more than UAH 2 trillion. Without hiding how much we still do not know.

What is behind the dry statistics of damage, how the war affects the soil and food quality, how toxic even the missile flight itself is, what we can do now, and whether the state has enough resources to properly document all war crimes against the environment — hromadske found out together with environmentalists.

The Kakhovka disaster: realizing the scale

Ecocide on the part of the Russian Federation has been discussed since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, and, of course, its most illustrative example was the blowing up of the Kakhovka dam by the Russians. Much has been said about the consequences of this man-made and environmental disaster: dozens of settlements and tens of thousands of hectares of protected areas were submerged, unique biodiversity was destroyed, the waters of the Dnipro and Black Sea became incredibly polluted, the irrigation system was lost, and the reservoir itself turned into a desert. The terrorist attack affected the lives of approximately one hundred thousand people.

Oksana Peklo is among those who were forced to leave the flood zone, having lost all their property. She and her family now live in Kryvyi Rih. Her house in the Korabelnyi district of Kherson was completely submerged: only the top of the roof was visible. The woman admits that when she returned home for the first time after the water came down, it was hard to recognize the house.

“It feels like someone just came in and turned everything over. The sofa was almost on the way out. The child's bed in the room was turned over, the table was in pieces… All the kitchen furniture fell, and the cupboards with all the dishes were on the floor. Everything was covered in silt. The water went away, but the silt remained, and the smell was unbearable. It gave me a headache,” Oksana tells hromadske.

Although the official results of the first soil samples in the city were mostly normal, she cannot come to this conclusion from her own observations:

“I also saw publications saying that there is no infection, the air is clean, the soil is normal... But, to be honest, when the water went down, there was silt left, and dead animals were lying right on the street. There was a stench of corpse. Of course, it will be impossible to grow anything on this soil, for example, in a year. Because you have to dig out the top layer - which is about half a meter - and bring in soil to make something grow there. I'm not an expert, but we'll keep watching.”

It could take centuries to restore the top fertile soil layer that was washed away by the strong flow of Dnipro water as a result of the Kakhovka dam explosion.

“If nothing is done, one centimeter of fertile soil is formed within a hundred years,” Liudmyla Biliavska, a scientist at the Zabolotnyi Institute of Microbiology and Virology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Doctor of Biological Sciences, tells hromadske.

Two months have passed since the disaster, but what the water carried and where it ultimately ended up is still not fully understood. In addition to washing away the top layer of fertile soil and most likely destroying the unique flora and fauna of the small steppe fauna, the water has also carried hundreds of tons of oil, the contents of buried toxic waste, landfills, cattle cemeteries, chemical warehouses, cesspools, and cemetery runoff. Environmentalists are not even talking about specific impacts: obviously, all these toxic substances have already reached the Black Sea basin. Some of it will settle on the road and get into the groundwater.

“In fact, in the lower reaches of the Dnipro and the Southern Buh and the surrounding areas, we had all sources of drinking water supply out of commission. The water in them did not meet the quality of drinking water. In some places, we took measures to clean them up, in some places we did not, because all of this is the territory of hostilities,” Anatolii Pavelko, an ecologist at the international charity organization Ecology-Law-Human, tells Hromadske.

Scientists and environmentalists from various organizations we spoke to took samples of soil, silt, and water, including in the Black Sea, where piles of debris had washed ashore. But now they say the research is still ongoing.

“We have taken samples of sludge, but they have not yet been analyzed in the laboratory. What is at the bottom, what are the components of that sludge, and is it safe — for this, we need to do a full study. You can't just analyze a few components and say, ‘That's it, it's safe, plant potatoes’,” says Anatolii's colleague, environmentalist Kateryna Polianska.

“We had people with us who took tests for virologists, who said that if it is ancient silt, there may be some preserved viruses there. I don't want to scare anyone, but as an ecologist, I would not grow or eat anything from that place yet. It is better to wait for the test results and know that it is safe. Tests take time,” she adds.

The ecologist also says that Ukrainian laboratories where samples for testing are sent ask what exactly they should look for, so before sending them, ecologists gather and discuss what can be found in certain samples.

Experts who said in the first days after the explosion that it was difficult to realize the full extent of the disaster have not become more accurate in their assessments. The main reason is that most of the territory of the left-bank Kherson region, which suffered the most, is still temporarily occupied by Russians.

Experts recognize that there is a lack of unification of all research groups. After all, point analyzes are lost in the immense scale of the problem, which has expanded to the entire Black Sea basin. So no one can say how to assess this scale.

And while nature would eventually be able to recover on its own (there are ongoing discussions about whether to intervene and rebuild the dam at all), the most affected link is the population itself.

Invisible toxicity: from soil to table

After the full-scale invasion, the regions with the most fertile land in Ukraine suffered the most. More than five million hectares of agricultural land have become unusable. And these areas are growing every day. They are littered with mines and ammunition, ravaged by sinkholes, and contaminated with oil products and toxic compounds.

Soil contamination with heavy metals is a huge problem. Research by scientists who have sampled soil in combat zones has shown that after a shell explosion, an excess of lead, cadmium, aluminum, copper, cobalt, manganese, and other metals appear in the ground. And as a result of the oxidation of explosives, sulfur and nitrogen compounds appear. In sinkholes, they can reach a depth of about two meters. Places where heavy equipment burned or oil products leaked are equally dangerous in the future.

All toxic substances migrate through the soil into plants. Therefore, in no case should you simply fill in the sinkhole and plant something on this land. Sunflower, wheat, and corn, in particular, can absorb the most toxic substances, says Liudmyla Biliavska, Doctor of Biological Sciences. Heavy metals can accumulate in the body and cause various diseases or even genetic mutations. And this applies not only to areas where active hostilities are taking place.

“We just don't see it, but there is a real danger for everyone. Even the very flight of the missile over the territory causes contamination of agricultural products,” says the scientist. “This situation, in particular, occurred in the Kharkiv region. The organic products of a farmer who has certified production were not accepted during the EU admission process because toxic substances from missile fuel were found during the analysis. It settles out of the air. It is unclear what the consequences of this may be.”

Experts from the NGO Ecoaction havecalculated that the explosion of just one old Soviet Tochka-U missile releases approximately 60 kilograms of emissions into the air. There are thousands of missiles launched by the terrorist country.

“When a missile, artillery shell, or mine detonates, several chemical compounds are produced such as carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, water vapor, brown gas, nitrogen, etc. In addition to these, toxic organic matter is also formed and the soil and wood in the affected area begin to oxidize. In addition, they leave a lot of debris behind. The total weight of a missile varies from 1300 to 2300 kilograms. Their remnants can remain dangerous even after the explosion. They need to be stored on concrete or asphalt to prevent toxic substances from entering the soil and water bodies,” thearticle says.

The same is true for construction waste that results from demolition. According to experts, it is imperative to equip special landfills and, if possible, reuse such waste in construction. However, there have been few concrete steps in this regard.

Hundreds of years for demining and conservation of territories

Recently, the Washington Post published stunning findings by the Slovak NGO GLOBSEC: at the current rate, it would take 757 years and tens of billions of dollars to demine the entire territory of Ukraine. Whereas the Ukrainian government was talking about decades.

The area contaminated with explosive devices is truly unprecedented and the largest in the world. One-third of Ukraine is now a minefield. We are talking about an area of almost 174 thousand square kilometers. It is the size of Uruguay or the US state of Florida.

“You have to go through the forests manually, you can't run a machine there. I don't know how many people are needed to manually go through the woods with mine detectors and check it all. In addition, there may be plastic mines, ‘petal mines’. It is difficult to hear them in this device because only a small part of it is metal. Therefore, as I understand it, some forests in Donetsk, Kharkiv, border regions, and the occupied territories will potentially be prohibited for visiting, as, for example, in post-war France,” says Kateryna Polianska, an ecologist at the international charity organization Ecology-Law-Human.

Environmentalists predict that Bakhmut, Soledar, Marinka, Avdiivka, and other towns and villages that have suffered the most destruction and have become a battlefield will be preserved in the future. After all, this land in ruins — dotted with thousands of craters, mines, and unexploded shells — will no longer be habitable.

Documenting environmental crimes: problems and challenges

During the full-scale invasion, the State Environmental Inspectorate recorded two and a half thousand cases of environmental damage. The Prosecutor General's Office is currently investigating more than 200 cases of war crimes against the environment. Of these, 15 are classified as ecocide (Article 441 of the Criminal Code). According to Ukrainian law, this is the mass destruction of flora or fauna, poisoning of the atmosphere or water resources, or other actions that may cause an environmental disaster.

The seizure and shelling of nuclear power plants by the Russians, the shelling of the Institute for Nuclear Research, the mass deaths of birds and dolphins, targeted attacks on oil depots, and the destruction of the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant, which was the largest environmental disaster since Chornobyl, are all unambiguous cases of ecocide. And, according to the Prosecutor General, Ukraine is the first country in the world to investigate environmental war crimes and ecocide on this scale.

However, the term “ecocide” does not yet exist in international criminal law. To recognize it as an international crime prosecuted by The Hague, international lawyers have been fighting for many years, and Ukraine may become a catalyst for this.

So far, this process has been unsuccessful. However, the International Criminal Court (ICC) can consider environmental damage in the context of war crimes. This is exactly what the Ukrainian Prosecutor General's Office is hoping for now, as ICC representatives have launched an investigation into the Kakhovka tragedy.

At its level, Ukraine can try the direct perpetrators. The country's first sentence for war crimes against the environment was handed down to a Russian general and colonel who, according to the investigation, directly supervised the seizure of the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant and the blowing up of the North Crimean Canal. They were sentenced in absentia to 12 years in prison and fined UAH 1.5 billion.

International investigations of environmental crimes can take much longer, as they require irrefutable evidence and expertise. And there are difficulties with documenting these crimes in Ukraine, says Olha Polunina, executive director of Ecoaction. From questions about the methodology for calculating damages to the lack of coordination between different agencies and the outright lack of resources to properly investigate all this.

“The desire (to prove environmental crimes in an international court — ed.) is very noble, but there are a lot of ‘buts’ here. Starting with the fact that the country has not introduced environmental monitoring at a normal level. That is, roughly speaking, how can I prove in court that these impacts from the oil spill occurred during the war if I cannot provide information about the soil samples that were taken ‘before’? I think this problem will crystallize when we start the trial,” Polunina told hromadske.

“In addition, laboratories are overloaded, not everyone knows how to do the necessary tests, and there are not always enough reagents. So both the state and NGOs are working on this somehow, but there is still no well-established system,” she adds.

According to environmentalists, it is very important that all government agencies responsible for natural resources now keep detailed statistics on what, where, and how they have been damaged. After all, it is Ukraine's job to record this as much and as thoroughly as possible. Whether this is effective or not will be determined by the International Court of Justice.

What can be done right now?

The population:

- In no case should anything be planted on the site of a sinkhole, burnt-out equipment, or near a spill of oil;

- do not swim in prohibited areas or take water, as toxic substances migrate through the soil into groundwater;

- do not try (especially for farmers) to speed up the process of demining fields by hiring “black” sappers;

- identify and report environmental crimes to the community head, the State Environmental Inspectorate, the Ministry of Environment, or online resources (such as the EcoThreat or Ecoinspector 2 apps, EcoShkoda or SaveEcoBot chatbots).

Communities:

- properly record cases of environmental damage;

- seek environmental solutions in recovery plans (focus on green recovery);

- depending on the level of land contamination, make decisions on conservation or reclamation.

The state:

- establish communication with the public;

- have a strategic vision of Ukraine's green recovery;

- to reform state environmental control and attract more resources to properly document war environmental crimes and unprecedented cases of ecocide to bring Russia to justice in international courts in the future.

Author: Oksana Ivanytska

- Share: