Lack of Direct Communication and Gadgets: How Online Education Impacts Children

The full-scale invasion interrupted the education of 5.7 million Ukrainian schoolchildren. Numerous educational institutions are now destroyed, and many children, along with their parents, have been forcibly displaced.

According to the Institute of Educational Analytics, as of May 2023, 1.46 million children were studying remotely, and another 1.2 million students’ education consisted of both online and in-person instruction.

Hromadske explains how education in Ukrainian schools has changed since the onset of the full-scale war, the challenges faced by school staff and internally displaced children, and how Plan International, together with #WeAreAllUkrainians and the BGV Charity Fund, supports students.

“Our School is Online, So That's Where We Stayed”

Nadiya Bondarieva is a mother and caregiver at a family-type orphanage. She and her husband Vasyl have 12 children — four by birth and eight adopted (six girls and two boys). Their biological children range in age from 13 to 25 years, while the adopted ones are between 5 and 13 years old. Nadiya says they "love them as their own," and the children, in return, call the couple "mom and dad."

“I come from a large family, and my husband was the only child, so perhaps he did not experience that,” Nadiya shares. “He said, ‘Let’s adopt a child, at least they will have parents.’ I love children, but we already had two of our own and a two-bedroom apartment. I told him I wasn’t ready yet.

We were friends with a family who took in four children. After a while, we also mustered the courage and decided to try to give them warmth, attention, and everything they needed. We first took in two boys, then another girl. We realized that we were doing well.”

Children sometimes have a hard time with everyday things and learning because of their background.

“The children are from disadvantaged families, their parents are in prison for drugs or have alcohol addictions, and one boy has fetal alcohol syndrome [FAS – Hromadske],” Nadiya reveals. “You say, ‘Do your homework.’ But he replies, ‘I don’t want to!’ They get nervous, some have a lot of aggression. We went through training on how to interact with children when they react this way. Without that, I wouldn’t know how to deal with it.”

Before the full-scale invasion, the 14-member family lived in Druzhkivka in Donetska Oblast. They had bought a house there as the family began to expand.

However, they had to leave their home, and since last September, the family has been living in the village of Senkivka in Kyivska Oblast. They sent the two oldest children, a 25-year-old daughter and a 17-year-old son, to Poland. The rest live under one roof.

Eight of the children attend General Education School No. 17 in Druzhkivka.

“Our school is online,” Nadiya explains. “Of course, the old system of education, with direct feedback from the teacher and communication with children, is more convenient. We have the opportunity to study offline here, but the school is small, and there are many children with complex backgrounds like ours. So we don’t have to explain to each teacher what kind of child this is and how to engage with them to avoid disrupting the lessons — because there have been such problems — we decided to continue studying online.”

"Education Quality Depends Not on Online or Offline, but on the Teacher"

Alina Orobynska is a mother of three boys. Her husband, a border guard, is currently serving on the front line. Before the full-scale invasion and during the first months of the temporary occupation of Kupyansk, Alina worked as a midwife in a maternity hospital. Now it's destroyed, as is almost the entire city.

At that time, the town faced a shortage of medicines and food, and people lived without electricity and water for about a month. In April 2022, mobile phone service and Internet connection were completely shut down. Alina recalls that period as extremely challenging psychologically.

"Russian fighters were constantly flying overhead; their sound scared us for a long time. We slept in our clothes. The children were on alert, ready to run to the basement at the slightest danger. Dima, my middle son, had his hair turn grey at the roots after the explosions," she explains.

On June 5, 2022, Alina left Kupyansk with her children and has been living in Kharkiv for a year and a half. She works as a paramedic in an ambulance. Her youngest son Mykyta is seven, her middle son Dmytro is eight, and the oldest, Tymur, is nine. The children attend grades two, three, and four at Kharkiv Lyceum №178.

"We went to a private school and studied there in September and October until someone told me that Natalia Serhiyivna had arrived," Alina recounts. "She was the homeroom teacher of my oldest in Kupyansk; all my children went to her for preschool preparation. We transferred to her school, and now she’s the homeroom teacher of my middle child. We wanted her specifically because she’s a godsent teacher."

Alina's oldest son had been through online education during the pandemic, so he has no issues with it. The middle one adapted over time, but it’s difficult for the youngest, Mykyta.

"He had his first grade online, the second too; he’s at home and doesn’t grasp the concept of school," Alina laments. "In the first grade, he could just get up and leave. He still wants to play and run around."

In Kharkiv, Alina's children have few friends and miss their home and familiar faces in Kupyansk.

"The oldest is particularly homesick because he went through kindergarten with his friends from Kupyansk, then they went to the same grade. You need to find an approach to him, he's shy, so it's hard for him," she shares. "Of course, the children want to go to school, to socialize with peers. However, the quality of education depends not so much on online or offline but on the teacher. If a child is interested in attending a lesson, then they will learn."

Currently, Alina’s middle son has taken a liking to mathematics and has become one of the best in the class at reading. The eldest has a strong desire to work with computers, and the youngest aspires to become a police officer or a soldier, like his father. Every return of their father is a celebration for the children.

“I See No Alternatives to Offline Education”

Natalia Kyrpychova, now the homeroom teacher of Alina's middle son, is a primary school teacher with a 23-year experience. She spent 22 years working at Kupyansk Lyceum №3. Windows were blown out in one of the buildings of the educational institution during a bombardment. In Kupyansk itself, says Natalia, two or three schools are completely destroyed and beyond repair.

After the outbreak of the full-scale war, Natalia's husband, an officer in the Armed Forces of Ukraine, was deployed, and she stayed in her now-occupied hometown. The principal of the lyceum offered her to continue working, but she declined.

On April 5, 2022, Natalia left for Dnipropetrovska Oblast with her relatives, taking her labor book and all other documents, and then moved to Kharkiv, where she found a job.

For the second year now, she’s been teaching online at Kharkiv Lyceum №178. In Natalia’s class, there are 24 children, 10 of whom are displaced persons. Three are specifically from Kupyansk. There are also those studying from Kyiv, Poltava, and Vinnytsia.

“I took over this class in the second grade and didn’t know what to do because the children were supposed to read 30 words per minute but were only managing 9-15,” the teacher recalls. “Not having mastered the first grade due to the war, the children can’t make up for these gaps.”

Natalia first gained online teaching experience during the pandemic and has since been constantly searching for new methods and formats to engage students.

“I worked hard to find new approaches, and I still do, to make it interesting for children to study,” she emphasizes. “I have to come up with creative things, using various team games through the Classtime platform. Today I devised a game, and it went well.

Distance learning is improving every year. For instance, there were only a few platforms two years ago, but this year there are many more. So every day, you search for something new, come up with things, attend various webinars, master classes.”

In general, Natalia sees more drawbacks than advantages in online education. She admits it's physically difficult for children to adapt to this format. They also lack socialization and discipline.

“In the online space, we communicate, but there is no live contact. They are scared of each other; they don’t know how to communicate,” a teacher explains. “When a child is physically in school, it disciplines them, but when studying remotely, it can be relaxing and sometimes hard to concentrate. However, even under these conditions, they still acquire knowledge, and the level of this knowledge is not bad.”

Initially, Natalia was skeptical about the education in the metro launched in Kharkiv this September but now believes that “if there were a chance to take my class and study in the metro, like in school — it would be superb.”

“I don’t see alternatives to offline education,” she emphasizes. “If it continues like this for another year, it will be an SOS for education. Therefore, we need to look for alternatives and proper shelters. Children’s education should be offline for live communication.”

Psychologists confirm that the lack of live communication is the most significant factor negatively affecting learning outcomes and the child’s personality development.

“Constantly being online leads to a reduction in empathy and can result in a child’s inadequate self-esteem,” asserts Andriy Rybalko, a psychologist at the Educational and Scientific Institute of Quality Education at Kharkiv National Medical University.

Also, the lack of active live communication negatively affects the development of thinking and language knowledge — all due to the absence of opportunities to give/receive feedback from the teacher, parents, or peers.”

Moreover, the psychologist notes that excessive use of online technologies for communication and learning exposes children to the risks of bullying, sexting, and other negative internet phenomena. However, online also has its advantages.

“Online education helps the child to be more independent and also contributes to the development of creativity and self-discipline,” assures Rybalko. “At the same time, offline, in war conditions, cannot guarantee the safety of the educational process, the life and health of the child and teacher.”

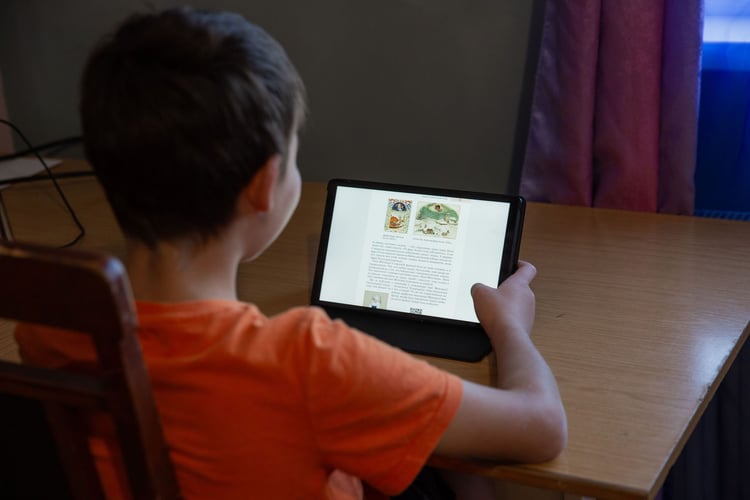

“Everyone Has a Tablet Now”

The issue with online education, as Natalia Kyrpychova points out, is also related to access to technical equipment, which often depends on the financial status of the parents. Many students in her class are forced to study on their phones.

“A phone has a small screen; they can’t see anything on it, and it affects vision,” the teacher says. “We live at a time when many Ukrainians have become significantly poorer. Not all parents can provide their children with a modern laptop.”

In the fall of 2022, when mass shelling of critical infrastructure and blackouts began, the team of Plan International, just starting its operations in Ukraine, conducted an analysis of the needs of the Ukrainian education system along with other organizations. Providing electronic devices became a top priority.

“So, together with the German initiative #WeAreAllUkrainians and the BGV Charity Fund, we decided to try to meet at least some of the needs and provide tablets for education to the most socially vulnerable segments of the population,” tells Natalia Katashynska, Emergency Education Coordinator at Plan International in Ukraine.

With the support of the Ombudsman's Office and social services, we identified categories of families eligible to receive a device, confirming their status with appropriate data and documents.”

Children from IDP families, aged 6 to 14 (including children with disabilities, children from large families, orphans and children deprived of parental care, and children from families in difficult life circumstances and receiving social support) were eligible to receive assistance.

We focused on IDP families from oblasts affected by the full-scale war, close to the front line or the border, and those hosting a large number of displaced persons.

“Our primary goal was to ensure access to education for children from the most vulnerable population categories,” emphasizes Katashynska. “Of course, just having a gadget does not guarantee this. So, it was crucial for us to promote the importance of education, especially during the war.

Together with partners, we developed a brochure with recommendations on using devices for learning and links to resources and applications that can be used for both formal education (all-Ukrainian online school VSHO platform, Can't Wait to Learn app, etc.) and informal learning, including safety and critical thinking development, which is extremely important now.

We also highlighted recommended resources for psychological support for children, as well as recommendations for children with disabilities.”

Children of Alina Orobynska and Nadiya Bondarieva are among those who received assistance as part of the project. Previously, Alina's elder son used her laptop for studying, and the other two were studying on their phones.

“Now everyone has their own tablet, the laptop has taken a back seat. They instantly mastered the tablets. They downloaded gamified math, they are solving problems like in a game. I haven’t figured out [the tablets] all that well yet, but the older one says, ‘Mom, you’re doing it wrong, look how it's done!’” Alina shares.

Nadiya’s children, until recently, were also forced to study using their phones. Now, each of the seven students has their own tablet. The family marked them for convenience so they could tell who owned which one.

“We had five regular touchscreen phones, then we bought two more,” Nadiya says. “At the end of last year, a small computer was sent from Druzhkivka. The children quickly figured out the tablets. There were tabs on how to load Google Meet, etc, conveniently. Plus, a year of internet and SIM card service already paid for. It’s just a dream — especially for families like ours.”

The telecommunications partner of the project, the organizers say, was Vodafone Ukraine, so over 5000 tablets are equipped with SIM cards with one year of pre-paid 4G Internet.

The delivery of all tablets was also covered by partners: Nova Poshta delivered all tablets to the recipients at the branches in seven oblasts of Ukraine for free.

Five Distance Learning Life Hacks for Parents

Adjusting to the online format can be achieved, psychologists assert, by following simple rules. Andriy Rybalko provides five life hacks for parents of schoolchildren:

1) Space Organization: Help your child establish and adhere to a daily routine.

Despite the transition to distance learning, treat school days as if your child were attending school in person. Ensure they wake up at the same time every day, dress appropriately, and have a healthy breakfast.

2) Educational Support: Reach out to your child's teachers.

Teachers are generally willing to communicate with parents via email or phone after school hours. Contact them if you notice your child struggling with the online learning platform or not completing assignments. Stay alert for any messages from teachers indicating they're having communication issues with your child.

3) Activity: Encourage physical activity and exercises.

Online learning means spending extended periods sitting in front of a computer. Encourage your children to use breaks to stretch, walk the dog, or do some light jumping — any movement helps!

4) Control: Resist the urge to sit in on classes with your child.

While it might be tempting to “drop in” and observe your child’s lessons, respect their privacy and the privacy of other students. Communicate with teachers via email or other communication channels before or after lessons.

5) Psychological Wellness: Take care of yourself.

No one can take better care of us than ourselves. If you neglect your own physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual needs, you will have less energy, space, and patience to interact with and care for your children. Even 10-15 minutes of scheduled “me time” during the day can make all the difference.

These days, safety is the top priority, but it's equally crucial to find ways to stay connected and communicate with others, be it your local community, school, or work.

If there are psychological support groups in your city or village, be sure to take the opportunity to join them, as many are eager to seek help or volunteer for neighbors or acquaintances who need it.

Reference information:

Plan International is an international non-governmental organization that advocates for children's rights and gender equality for girls. We strive for a world of justice, working alongside children, youth, our stakeholders, and partners. Our mission is to foster a world that safeguards children's rights and promotes equality for girls. The organization’s representation in the country is part of the Ukrainian response hub, which also includes work with refugees in three host countries — Poland, Moldova, and Romania.

The non-profit organization #WeAreAllUkrainians has grown from the ad-hoc initiative of Dr. Volodymyr Klitschko and Tatjana Kiel in the first days of the full-scale war in Ukraine. Led by two directors, Tatjana Kiel and Dörte Kruppa, the initiative implements extensive and long-term measures and projects with a broad network of partners and volunteers in Germany — for people in Ukraine and from Ukraine. #WeAreAllUkrainians also responds to the most urgent needs in Ukraine, which are a focus of Volodymyr Klitschko in Kyiv.

The BGV Charity Fund was established by representatives of Ukrainian businesses in March 2022 to organize assistance to Ukraine during the war and the country's reconstruction after victory. Currently, the foundation is involved in organizing the delivery and distribution of humanitarian aid to Ukraine, as well as comprehensive charitable projects and initiatives for those in need — children, IDPs, military, elderly people, vulnerable populations, and more. The foundation's main areas of work include providing food and non-food humanitarian aid to the population, children's and educational charitable initiatives, and supporting Ukraine’s defenders.

This content is published as an advertisement.

This publication was prepared within the framework of the project “Providing access to education to vulnerable children impacted to Ukraine Crises” implemented by the non-profit assistance organization #WeAreAllUkrainians in partnership with the representative office of the international organization Plan International in Ukraine. The content of the publication reflects the position of the authors and does not necessarily represent the perspective of Plan International.

Contributors to this material include journalist Dmytro Kuzubov, editor Viktoriya Beha, designer Myroslava Mokhnatska, and creative producer Kateryna Vyshneva.

- Share: