'Most are absolutely not inclined to give in to aggressor's whims': Sociologist reviews 2025 and forecasts 2026

The year 2025 brought sociologists an unexpected finding: Ukrainians have started treating one another better. Shared hardships and collective resistance have opened their eyes to their own qualities — positive, courageous, and resilient.

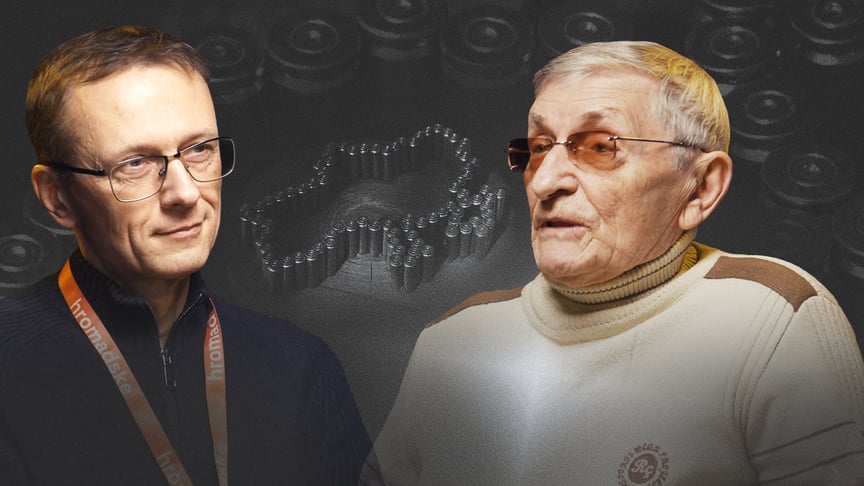

At 75, Yevhen Golovakha, director of the Institute of Sociology at the National Academy of Sciences, has spent decades studying the moods of Ukrainians. He admits that, as a scholar, he adheres to a principle that is not great for him as a person: the worse things are for society, the more interesting it is for sociologists to study. War, he says, is a profound horror against which astonishing phenomena emerge. He calls 2025 a year of adaptation "to the terrible situation we found ourselves in nearly four years ago."

Currently, 25% of Ukrainians are in a state of distress and need serious psychological help. In 2021-2022, that figure was 11%. Still, despite war fatigue, losses, and stress, 54% of Ukrainians oppose territorial concessions, according to a survey by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology. The number of those open to giving up territory has risen, however, from 8% in 2022 to 38% in 2024.

Referring to U.S. proposals and President Volodymyr Zelenskyy's willingness to hold a referendum on possible territorial concessions, Golovakha says the decision should indeed be made by all Ukrainians. But there is no point in holding a referendum, he adds, because polling data already shows that "most are absolutely not inclined to give in to the aggressor's whims."

hromadske’s Kyrylo Loukerenko: What do you think about the possibility of elections in 2026 if the war ends? Will there be surprises?

Yevhen Golovakha: Frankly, trust in the [Verkhovna] Rada is very low. Unfortunately. Our research, and that of other polling centers, shows that among all political institutions, the Rada has the lowest level of trust. Even the government has higher trust, though it is new and hardly anyone knows it.

This is some kind of tradition for us: Ukrainians have always rated the Verkhovna Rada the lowest among political institutions. Perhaps they expected a lot from it and feel that lawmakers have not lived up to their hopes.

As for the president, evaluations are generally positive. These are the latest data from KIIS. Though a corruption scandal ("the Mindich case" — ed.) led to a loss of about 7% trust, from 65% to 58%.

But Ukrainians will still be engaged in these presidential elections. One polling center checked potential candidates. It turns out that, abstracting from the "what if" scenario, the serious figures are obvious: Valerii Zaluzhnyi and Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Those are the ones who get the most votes.

So you do not expect surprises in the presidential race?

Not yet. You understand, this is an utterly absurd situation — there is no political life yet, let alone political competition. Perhaps when political life starts, people will emerge who draw major attention — who knows.

There are those who support, say, [Petro] Poroshenko, or even [Yulia] Tymoshenko — politicians who were leading figures before the war. There are those who back volunteers like [Serhiy] Prytula and others. But that is an order of magnitude less than those two candidates.

If elections to the Rada happen in 2026 and military commanders run en masse, will they be strong candidates in the political landscape? Could we see a Verkhovna Rada half or even three-quarters made up of commanders?

I do not think everyone is considering a political career. That is not that many people, by the way. I do not see the Verkhovna Rada having a majority of people tied to the military. Though there will be some. They could become leaders, in fact. But for it to be a mass trend, with army leaders becoming politicians — I do not see that.

People who have a taste for politics are special. I can say from my own experience. I received many offers to enter politics and take it seriously. And what do you think? I immediately said: "What, me? For what?" It is a field that should be professional, but few are suited to it. It requires very specific personal and professional traits. And there are not many such people. I do not think many will be found.

Remember the Cossack Havryliuk from the Maidan? For me, he is an example: though he became a symbol of spiritual resistance, that doesn't mean he is a politician, you see? Politicians are, first, individuals with unique traits, and second, they possess organizational talent and abilities.

Do you think we could have an entirely new political landscape?

It could happen. I am not insisting — I do not know. It could be a phenomenon of the war itself. Support for nationalists has grown substantially over the decades, from 3% to 18%. I support them because they are the most principled advocates of resistance.

We can say these people's views have transformed, because the president's views have transformed. He came in 2019 as one person, and now he is completely different.

Absolutely! He is not a nationalist, but he is now no less a national democrat than the national democrats of the 1990s. He will never be an extreme nationalist — that is clear. But he is in that spectrum, close to supporting nationalists, in my view.

So he has pulled some of his voters...

Yes, precisely toward the national movement. For survival and victory. That is why I say I am not judging now that Ukrainians are more supportive of nationalist tendencies in politics. Because this is a survival situation. What comes next? I hope the Ukrainian political spectrum will become more balanced.

Moreover, in Ukrainian political life, personal tendencies have always outweighed ideological ones. For Ukrainians, who leads a political force mattered more than its ideological foundation.

So, if vibrant leaders emerge who back, say, a liberal direction, political life will not be so uniformly focused on nationalism.

I am a scholar — and scholars, especially in humanities and social sciences, are most often oriented toward liberal politics. What is liberal? The kind that gives maximum freedom. A scholar cannot live without freedom — they disappear. I very much hope that bright, liberal leaders will emerge.

So you think we will not have a political landscape based on party priorities?

Yes, our parties are personalistic. There is a leader — there is a party. Take Batkivshchyna. There was Tymoshenko, there was Batkivshchyna. But what is Batkivshchyna without Tymoshenko?

Or European Solidarity without Poroshenko. Or Servant of the People without Zelenskyy. What is that? What's the ideology of the "servants"? Tell me, please. But they support the president. That is the whole ideology.

Do you think there will be no more political ideologies in Ukraine?

No, why not? I think there should be, but it is a long process. Unfortunately, we are utterly inexperienced in political life. As in state management, by the way. I once referred to it as a macro-management vacuum. Back in the 1990s, I warned that we had no macro-managers at all. Those who existed just carried out whatever the central authority in Moscow told them when we were part of the Soviet Union.

Therefore, it will be very challenging for us to create a new political space with ideological parties, without this obligatory personalistic element that now encompasses everything. The main thing is peace.

How do Ukrainians feel about the military now? Do surveys show a change in attitudes toward those serving in territorial recruitment centers?

We need to distinguish right away. Attitudes toward the Armed Forces of Ukraine, as the force preserving the country, are extremely positive. The same 90% trust as before. The only institution that has suffered minimal losses is the Ukrainian Armed Forces overall.

Toward TRCs, it is the opposite. Rating [think tank] conducted a survey this summer asking: "How do you feel about TRCs?" Over 60% were negative, and only about 27% positive, I think.

However, these are the same military forces, the same Ukrainian Armed Forces.

Public opinion is a strange thing. There is a category called ambivalence. I studied it as a scholar: when people hold mutually exclusive positions simultaneously. It is a known phenomenon, first discovered in psychology and psychiatry. It then turned out to exist in social life as well.

Ukraine was in a state of absolute ambivalence for nearly 25 years before 2014. Ukrainians were ready to move toward the West and East simultaneously. We see where that led. You cannot move in opposite directions at once. However, this is quite characteristic of both mass consciousness and individual consciousness.

Even in everyday life, one can experience both love and hate. That is emotional ambivalence. But there is intellectual ambivalence when you accept mutually exclusive alternatives. This is exactly that. On one hand, the army is everything to us. Without it, we would already be slaves. Some would have fled West, some hidden in basements in Russia, some kept silent.

On the other hand, there are concrete children, husbands, relatives, friends, and colleagues who could be mobilized. Especially since we are aware of cases of "busification." So attitudes toward this part of the army [TRCs] are generally negative. And honestly, it is hard for people to understand that without this part, there would not be the one they fully trust. That these are the same soldiers.

A few months ago, a poll sparked considerable emotion and discussion — 42% of the population did not condemn draft dodgers.

And how many condemned them?

Fewer. About 33%. There were also those undecided. It is hard to decide here — if you have someone who could be taken into the army, but you or they do not want it, it is a very tough question. I see this duality in people's consciousness very clearly: on one hand, we value the army above all; on the other, if someone does not want to join, let them be.

This needs serious discussion and resolution. If a person is afraid or fundamentally unwilling, will they not become an internal factor undermining the army later? There are problems here.

I once read diaries of Central Rada member Serhiy Yefremov, who after World War I wrote in the context of war something like: "people have been utterly corrupted." Meaning war changed people for the worse, he thought after World War I. How is the current war changing Ukrainians? Does it trigger positive changes or make them worse?

It is ambiguous. It changes them differently in different ways. In some cases positively, by the way.

Take social cynicism, which we study. People who say "you cannot trust people" or "most would do something dishonest if it benefits them" — there are fewer of them now.

We treat one another as more decent, and it is clear why. We are suffering: some die, lose loved ones; others live 16 hours without power. These are different, but it is a very hard psychological situation.

People endure it, remain human, keep working, living, supporting. And how many volunteers constantly helped the army and those in need... Ukrainians have started treating one another better. They rely on each other more. That is positive.

On the other hand, they are more nervous. Their health is worse, especially mental health. In this sense, we are severely affected by the war factor.

What do Ukrainians expect in 2026?

You know, Ukrainians are not as optimistic as in 2022 or early 2023. Before our counteroffensive failed. Remember? They thought the war would end in months with our victory. At most a year. That was the overwhelming view.

Now Ukrainians understand it is unpredictable. According to the Institute of Sociology's 2025 survey, 60% said they do not know when the war will end. They have realized they will have to live in these conditions for who knows how long.

On one hand, they do not know when it will end. On the other hand, the vast majority still does not want concessions to Russia. It is simultaneous. But they hope for peace.

Ukrainians believed [U.S. President Donald] Trump would resolve something for them. Only 27% thought Trump would not help at all. Now 72.3% distrust him. But they still hope for possible peace.

Ukrainians expect one thing from 2026: that the Russian economy will be in such a state that [Russian leader Vladimir] Putin's inner circle will go on their knees and beg: "Dear father, stop, or we are all done."

We must rely first on Ukrainians' resilience. And they are demonstrating it so far. The only thing Ukrainians are ready for — and this gives authorities carte blanche — is stopping the war on the line of demarcation.

Are issues like economic reconstruction, demilitarization, troops coming home, veterans returning to civilian life on Ukrainians' radar? Do people think about this?

They do. In our institute's surveys, there is a question: "What potentially conflict-prone situations do you see in Ukraine now?" According to the latest data, the most conflict-prone issues are mobilization and declining living standards. Over half of the citizens think so.

Conflicts related to those returning from the front, those who left abroad, or internally displaced persons — only 8% to 12% see these as potentially conflict-prone. That does not mean they do not exist, but people do not yet see prospects for serious conflicts with these groups.

Since 2022, many have become internally displaced or left for Europe. What do Ukrainians think about their return in 2026? And what do those now in Europe think about returning if the war ends?

There are data from the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology from early this year. Up to 87% had positive attitudes toward those abroad. And even more positive toward IDPs.

Overall, positive attitudes prevail. Though, of course, that does not mean there will not be conflicts over "I stayed here through the war, and you were there," etc. There will be, but in my view, they will not be mass phenomena. That is my forecast.

The other question is whether people will return. Demographers are more aware of this, and they tend to be fairly pessimistic. In the Balkans, after four years of war, 30% of those who left for Europe returned to Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia. What makes us especially different? In this sense, maybe 30% will return. After four years. After five, perhaps less. Maybe 25%. Of course, children have studied, found jobs, and have housing. And possibly men will go join women there.

I think there will not be mass returns, but several million Ukrainians will definitely come back. And that will be serious reinforcement for Ukraine, I believe. I see it more positively than in terms of conflicts. But we need a serious program for their return, since many no longer have homes.

Though honestly, I think even the 70% who do not return will benefit Ukraine. How? They will support it. First, they will send money to relatives here. Second, they will create charitable and volunteer organizations. No doubt.

This will be a new wave of diaspora oriented toward supporting Ukraine. I believe these people will continue to visit Ukraine as tourists. They will have great nostalgia. Later, perhaps with some capital, they will become investors in Ukraine.

So we cannot see it as an absolute negative. It is normal life. If they are in Europe, they will bring certain European life skills to Ukraine. Though we have chosen to be Europeans, in consciousness, we are still far from it, to be frank.

- Share: