‘Those who join army for money soon become KIAs.’ Why first young woman signed youth contract under new program

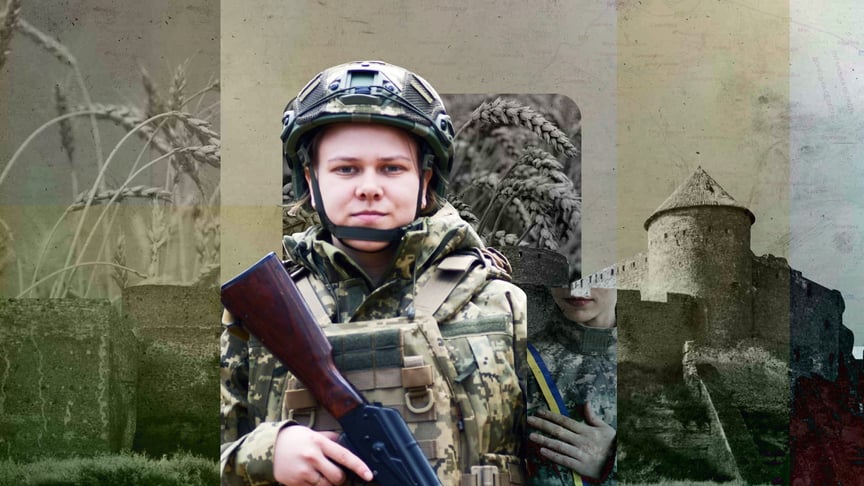

Veronika, the first girl to sign the “million-hryvnia contract” with the Ukrainian Armed Forces, now goes by the call sign Lyalya. A senior sergeant in the 72nd Brigade suggested it, and commanders’ decisions aren’t up for debate.

We’re talking to 21-year-old fighter Lyalya over the phone — she’s squeezed in a brief moment during a break from military training. She doesn’t want to miss a second of it because skipping even a minute in combat conditions could cost her life or the lives of the soldiers she’ll save as a future riflewoman-medic.

And I don’t see her determination as naive youthful idealism. She fought too hard, for three years (!), to become a soldier to now — with her dream finally realized — carelessly slack off.

“From the military commissariat’s perspective, I had a lot of flaws: I’m a girl, I’m younger than draft age, I don’t have a military specialty. So all paths to mobilization were closed. They didn’t want to sign a regular contract with me either — for the same flaws. For me, the 18-24 contract isn’t about 1 million hryvnias; it’s about a chance to finally get to the war,” Lyalya said.

To me, Lyalya’s story is about persistence and a clear sense of purpose.

Military recruitment office at 18

In January 2022, just before the full-scale war, Lyalya turned 18. She was studying to be a paramedic-midwife at a medical college in Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi. She immediately decided she’d try to join a frontline medical unit. She didn’t say a word to her mother at home.

“I never planned to be a soldier; I always wanted to work as a medic. But when the war started, I realized that if I wanted to live under my flag in my country, I had to do something. I wanted to help our guys on the front line by becoming a combat medic.

I didn’t care that I was very young and had no experience. The main thing is motivation. With motivation and desire, a person can learn military skills even at 18,” Lyalya recalled of her mindset back then.

Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi is her hometown, so in February 2022, she went to the local military recruitment office (TRC) to enlist. But no one took her seriously: “Look at all the grown men trying to join, and you, a student girl, go keep studying.”

Lyalya proved to be one of those people who get more determined when faced with obstacles. After the TRC rejection, she started exploring other enlistment options.

In 2023, she tried joining the border guards. Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi, a border city, has plenty of relevant units. Lyalya attempted to sign a contract with one.

A year had passed since her TRC failure; she was now 19. But the border guards didn’t want her either. They said they didn’t need medics and had no openings for specialized roles.

Still, Lyalya wanted to serve. For her, it was a matter of principle.

Finishing medical college could’ve theoretically solved the specialty issue. With a diploma, she’d be a professional, not a student, asking to enlist. But Lyalya had to drop out — her family couldn’t afford her tuition anymore. She took a job at a local factory. It seemed she’d drifted even further from her army dream.

Working at a military hospital or civilian clinic to help soldiers recover didn’t appeal to her.

“During college, we volunteered at such medical facilities — it wasn’t what I wanted. I wanted combat positions,” Lyalya explained.

In January 2025, she went back to the Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi TRC, asking to be mobilized to any unit, any role. They told her there were no vacancies, not just in the city but across all of Odesa Oblast.

“It was an excuse. I’d turned 21; it was hard to say I was practically a kid anymore. They couldn’t fault my physical fitness either — I’d been training. I had no husband or kids — the TRC asked about that, so it mattered to them. By family status, I was a better fit than an older married woman with children. But they still didn’t take me,” Lyalya said, still upset about the unfairness.

She’s convinced that if a guy her age with her motivation and fitness had shown up, he’d be at a military unit training the next day.

So what could she do? She couldn’t become a guy or instantly turn 25. She had to fight to be accepted as a girl below draft age. By the way, Lyalya said she was the only girl at her TRC pushing to join. No matter how often she went, she never saw other girls vying to compete with her.

Then, a few weeks after the TRC brushed her off again, as she feverishly weighed her odds and gathered strength to start over, news broke about a contract option for Ukrainians aged 18-24.

Applying to four brigades at once

“I downloaded the ‘Reserve+’ app because it let me apply to the government’s experimental project on my own. I loved that military units I could contract with couldn’t reject me without a solid reason. My gender and lack of a diploma weren’t valid reasons for refusal in this project,” she said.

Under the project, only a few brigades and a limited list of specialties were available. Lyalya aimed for riflewoman-medic and wrote to four brigades, highlighting her strong fitness, basic paramedic knowledge despite not finishing college, motivation, and not being tied down by a family.

One brigade called back politely, another refused, a third ignored her. Only the 72nd responded constructively:

“Literally the next day, they contacted me, asked about my residence, family, education, what role I wanted, standard info. Then they said I’d sign the contract in Bila Tserkva, where the brigade’s based. A recommendation letter about me would go from the brigade to the Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi TRC, and I’d do the first selection stage at my local TRC. They had to check if I was physically and mentally ready to sign,” Lyalya recalled.

To prove her fitness, she had to do at least 20 push-ups, max out sit-ups in two minutes (she managed 45 — enough), and run 100 meters, 2 kilometers, and 3 kilometers.

“If you want to serve, you’ll train constantly. The TRC has the requirements listed. I learned them back in 2022. I hit the gym and stadium 4-5 times a week. I knew I needed good fitness to pull out the wounded,” Lyalya explained her strict regimen.

Psychological tests assessed her motivation for service, readiness for war’s realities, and ability to work in a military team.

“You can’t pretend to be someone else, hide anything, or lie. You can’t guess what answer they want or what’s ‘right.’ There’s no set right answer. The tests are designed to reveal your personality as a whole,” Lyalya said, sharing the secrets of the psych evaluation.

She passed the Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi TRC tests successfully. The officials compiled her file, handled the paperwork, she cleared the medical exam at home, and headed to the 72nd Brigade’s recruiting center in Bila Tserkva.

“My military friends knew I was trying to sign a contract; my 11-year-old brother found out first — he can keep secrets. I told Mom right before leaving for Bila Tserkva so she wouldn’t worry early. I just said I was going to sign a contract,” Lyalya added.

She went to the brigade alone, with no friends or family. Into adult military life, she brought only documents and hygiene items from home. Why haul a caravan when the unit provides everything?

Sentimental stuff like makeup, a favorite dress, or a plush toy? Not Lyalya’s story. She didn’t even know what to say when I asked. Makeup in war is absurd. It barely interested her in civilian life.

Don't chase romance

At the recruiting center, the same tests awaited: psych evaluations and fitness. It was thrilling yet scary — what if she failed here, so close to her goal?

She didn’t. On March 27, she signed up with the 72nd Brigade alongside five guys from across Ukraine.

“I know other girls aged 18-24 applied for the contract besides me. But I was the only one who passed. Maybe they weren’t as prepared as me. If I hadn’t made it with the 72nd, I’d have kept looking for a regular contract — I’d have gotten there anyway.

The experimental contract made it easier for young people to join because their age became an advantage, not a flaw. The million they’re supposed to pay us isn’t the point. I don’t even think about that money or plan how to spend it. Those who join the army for money soon become KIAs — I’m convinced of it because they don’t get where they’re going. War isn’t about earnings,” Lyalya said confidently.

She’s the only girl in her training group among guys. She might be the only one in her combat unit later. It doesn’t faze her.

“The guys treat me differently now. Some try to help me as a girl; others talk to me as an equal, not focusing on my gender. Both ways work for me. In combat, I think I need to be like everyone else — a fighter. Not remembering my gender on the front line or holding onto female dignity. Like not tolerating rude remarks or jokes about me or around me. Overall, I don’t feel any discomfort in a male group right now,” Lyalya said confidently.

Among her female friends in Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi, she’s the only one who joined the army. They took her choice positively; some are now considering Armed Forces contracts too.

“When you’re set to serve, don’t romanticize the army, war, or soldiers. Don’t join the AFU for a cool uniform, male company, or hopes of finding love. You’ll get disillusioned fast — romance seekers often end up among the KIAs,” Lyalya said with unyouthful seriousness.

At the time of our talk, only four days of training had passed since signing out of the program’s 45. She’s on the theoretical course now. Nothing’s been tough yet. She’ll find out how she handles the training when she gets there.

When training ends, riflewoman-medic Lyalya must be ready to provide medical and first aid to frontline fighters, assist in their evacuation, and more. No romance here — just huge responsibility.

- Share: