'Serve or be punished': How Ukrainian teens dodge Russia’s forced conscription

“Almost all my classmates went into the army. There were eight of us in the group: two others and I did not go,” says 20-year-old Crimean Vasyl. He received his first draft notice two years ago at work — and has been in hiding ever since.

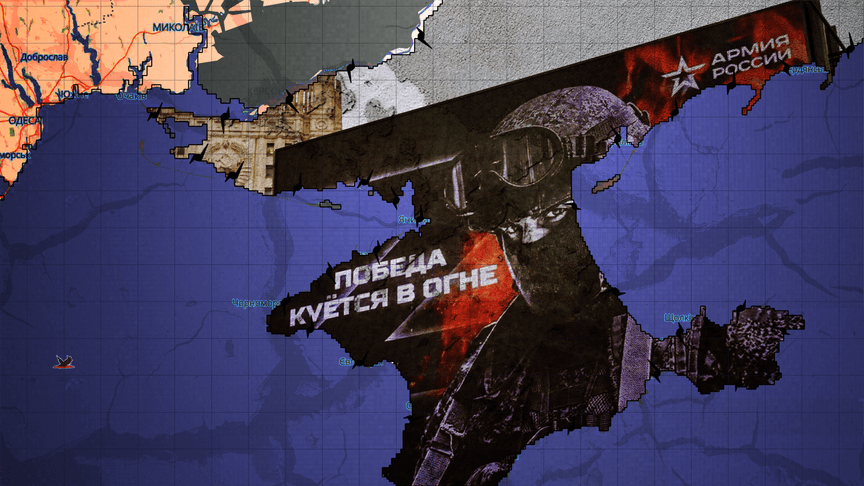

In 2024 alone, Russians conscripted about 5,500 residents of Crimea, and since 2015, the total has exceeded 50,000.

“In school, the whole focus was on convincing us that we are ‘Russians’ and were never Ukrainians,” Vasyl says.

As of January 1, Russia abolished spring and fall conscription campaigns for mandatory service. Now they will take place year-round, including on occupied territories — even though this constitutes a war crime under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

Vasyl is from Crimea, Bohdan hails from the occupied part of Zaporizhzhia Oblast. The young men left their home regions to avoid being forced into the Russian army. In December 2025, they crossed the Belarusian-Ukrainian border and arrived in Kyiv. Here is what they told us.

Vasyl

The occupation began when I was nine years old. Unfortunately, some of my relatives are pro-Russian. Back then, I was already under the influence of propaganda and expected everything to end with a “referendum.” At nine years old, I think, you can believe anything. I just wanted it all to be over. I did not think about how exactly.

School changed very quickly. They said nothing at all about Ukraine. That topic became taboo. Flags changed fast, teaching materials, and textbooks. They also hung portraits of [Vladimir] Putin — he was in every classroom. There were periods when the Russian anthem played every morning at school.

I finished ninth grade and enrolled at the Romanovsky College of Hospitality Industry in Simferopol. The administration there was very pro-Russian. Even before the full-scale war, someone was expelled for posts about Ukraine.

I started watching Ukrainian YouTubers, streamers, and more youth-oriented content. I also read Ukrainian Telegram channels.

I received my first draft notice at work when I turned 18. I was working in a café. After that, I realized I could not stay there. There would be problems; they would look for me.

I went to Russia so they could not find me quickly. I later learned that the next day, they issued me another notice at the military enlistment office.

At first, I told all my relatives different information, even that I had gone to another city — not the one where I actually was. So if someone from the enlistment office came, they would not know where I was.

The relatives’ reaction was simple: “Go serve, it is only a year.” But when I said I am Ukrainian and do not want to serve in the Russian army, a scandal erupted. Any conversation about Ukraine ended in a fight. There was no real support. They only talked about how if I did not serve I would not get a job anywhere and could not get employed.

I had planned to go to Kherson before I turned 18 and get a Ukrainian passport. But the full-scale war began when I was 16-17, so I had to postpone that plan.

I moved around a lot in Russia and worked remotely as a bank support operator. In November 2025, I asked artificial intelligence whether it was possible to get to Ukraine without documents. It answered that it could be done through the EU or Moldova, but the best option was the humanitarian corridor from Belarus.

After that I started looking for information on Telegram. I found several chats. Then I contacted a guy who, like me, is from Crimea. He gave me contacts of volunteers who explained in detail what and how to do.

Now I am in Ukraine. My relatives do not know. I told only my sister. We have a normal relationship. She supports me even though she holds a pro-Russian position.

Since I currently have no documents and did not receive a passport before turning 18, I need a witness to confirm that I am me. That is required to process documents.

This confirmation takes place at the State Migration Service of Ukraine. It can be done remotely via video link. And out of all possible candidates for witness I have only my sister, because my mother, for example, no longer has a Ukrainian passport. I do not know where it went, but it is gone. My sister has a Ukrainian passport. She is currently in Crimea.

Bohdan

When the occupation began, I was 14 and finishing ninth grade in Berdyansk. I went to a vocational college. I did not plan to enroll but there were just no options. I had to go somewhere so there would be no questions about why I was not studying or why I had no documents.

In college there were separate classes where they explained how good Russia is. They said the Ukrainian army destroyed Mariupol, while the Russian army is kind: it helped people, cleared rubble, and delivered humanitarian aid. Those classes were every Monday and mandatory. We had to carry out the Russian flag and stand under it before lessons began.

If you simply did not show up there could be questions. If it happened repeatedly they could call the police. It did not happen to me personally, but classmates had their phones checked.

The college director was brought from Russia right after the occupation began. Among ourselves we talked, and basically everyone was pro-Ukrainian; we just did it secretly.

In my second year they put me on the military enlistment register. They took us straight from class to a psychiatric hospital. There we filled out documents, then they let us go. They said I was free until 2026, and then they would take me into the army.

My father was against it. He said they could take me somewhere, to the war, and trick me into signing a contract. My mother said: “What can you do? You have to.”

The idea of leaving appeared a long time ago. When I was 16 a friend left and said it was realistic. I wanted to too, but I was not yet 18. I waited. When I turned 18 they closed the border between Belarus and Poland. I thought that was it, no options. But it turned out you could go through the Mokrany-Domanove checkpoint.

My parents did not plan to leave. They have a house and an apartment there. They were afraid that if they left, everything would simply be taken. My mother knows I am in Kyiv now. She is not against it. My father is no longer here; he died. He also wanted to leave after me, but never got around to it.

Next, I plan to live, work, or study abroad for about 2 years, then return to Ukraine.

"Propaganda is a hidden form of coercion"

Kateryna Rashevska, an expert with the Regional Center for Human Rights NGO and a PhD in international law, told hromadske that human rights defenders have documented the following pattern in occupied territories: a person is first conscripted, then pressure begins to make them sign a contract with the Russian Armed Forces.

“We must understand that Russia insists there is supposedly no mobilization, only contract service. That also shapes the overall narrative,” Rashevska says.

According to Ukrainian intelligence, during the fall 2024 conscription campaign in the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia oblasts, Russians enlisted about 300 men.

“Under Russian law, the conscription age is 18 to 30. We are talking about a very large group of people. Some of them were children or teenagers at the start of the full-scale invasion. So someone could have been 14 years old,” Rashevska adds.

Forced mobilization and forced conscription are war crimes under the Rome Statute.

“Propaganda is a hidden form of coercion. When it starts in school that supports qualifying it as a war crime. The very circumstances of occupation — fear, lack of freedom — create a coercive effect and also work toward that qualification,” Rashevska explains.

In particular, for conscription “evasion”, Russian occupation authorities can impose a fine of up to $2,589 (200,000 rubles) or imprisonment for up to 2 years.

This report was prepared with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. The report represents the authors’ position and does not necessarily reflect the position of the International Renaissance Foundation.

- Share: