A life of faith through wars and hardship

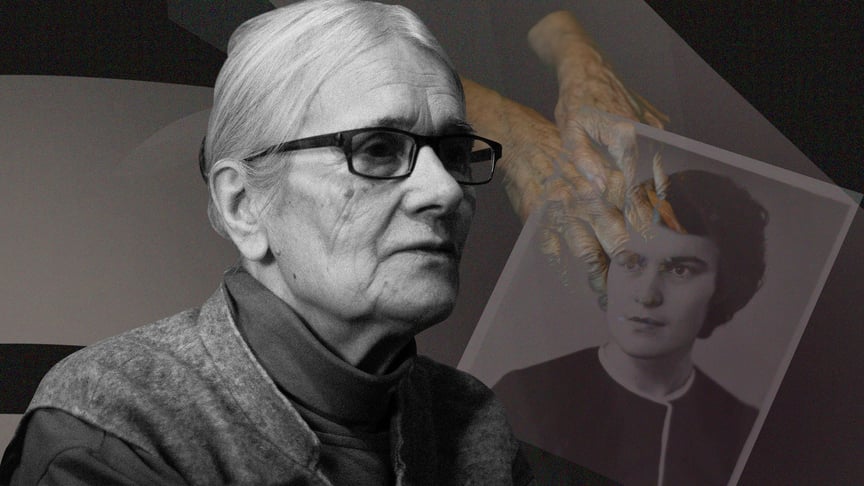

Nadiya Kotsiubynska's neatly braided blond hair does not betray her age. She now lives in an apartment in Kyiv with a female IDP she took in during the war. In her early childhood, she experienced what it was like to hide from shelling and lose her home.

"My sister died of hunger, and my parents' house was taken away from them"

The woman rubs her hands together and begins to talk about her past.

"I was born in the village of Solonytsia, Poltava Oblast, in 1937. My parents had three of us. One of my sisters died as a newborn during the Holodomor in 1933. My mother was very swollen from hunger.

My parents had a nice house, but the communists took it away and kicked my mother, father, sick mother-in-law, and grandfather out. We lived in other people's houses. Even the cow was taken away. So my grandfather buried three bags of peas in a ditch. Thanks to them, we survived."

Recalling those memories, Ms. Nadiya's eyes welled with tears. She often looks down. I notice how much pain is in each tear. The woman has written down her childhood memories on sheets of paper, for history, she says. She hands me these sheets and continues to tell me about herself.

"I remember the Second World War well. I was six years old back then. I remember the bombing. My father was taken to the front. Before the war, he was the head of a collective farm, and people respected him.

I remember that in 1943, my father came home for three days on leave after being wounded in Stalingrad. Those three days flew by like a moment, and he returned to the war again, and in 1945 my mother received a death notice. So at the age of 26, she was widowed with three children. My younger sister was 2 years old, I was 6, and my brother was 8.

In 1943, the Germans were marching through Poltava Oblast. They bombed our village heavily. We were hiding in the cellar. My mother took feathers and pillows, covered the cracks and walls, because someone said that shells would not pass through feathers. One bomb fell nearby, near the house, and left a big crater.

German soldiers often molested young women and girls. So my mother would put on an old grandmother's skirt, smear it with cow dung, wrap herself in an old scarf, as old women used to do, and put on the worst clothes so that they wouldn't pick her."

Nadiya recalls how in those difficult times there were also warm and pleasant moments that the war could not take away. She remembers how a German soldier, who also had three children of his own, came up to them, the little ones, and started stroking their heads.

"He said: ‘Kinder, kinder’, explaining that he had children too. Then he took out chocolates and gave each of us a chocolate. Usually, ordinary German soldiers did not hurt children. On the contrary, they tried to help them. And what the Russians are doing now, it's unbelievable," Nadiya is outraged.

"Back then, most people were poor but welcoming"

Nadiya's father never returned from the front. He died in 1945 on the German border. As an adult, the woman visited his grave. The war left behind only tears, cold, and a second famine.

"The postwar years were hard, there was nothing to heat the house with. There was a steppe around, no forests. We made briquettes from manure and burned them. It was so cold in the house that we slept only with our clothes on. Even the water froze into a block of ice.

In 1947 there was also a famine. My mother worked as a milkmaid on a collective farm, and sometimes the storekeeper gave her bread. We did not feel hungry, but once a boy and a girl came from Kharkiv. They were already swelling up, they came to our yard and ate cakes and all kinds of grass.

My mother took these two children into the house and first gave them serum to prevent intestinal distress. Then she gave them cheese and milk, which we had thanks to the cow. They stayed with us for two weeks. It turned out that their parents had died. Then other people took the children in. Most of the people were poor back then, but they were welcoming."

The mother prayed that none of her children would have to work on the collective farm, because the work was hard and the pay was poor. The survivor's benefit did not help either.

"My mother received a pension for the loss of our father - 7 karbovanets, 50 kopecks. It was a drop in the bucket for three children. That's why my grandmother helped us. Whenever I visited her, she would feed me. And I loved going from school via my grandmother's yard. She would cook very good borshch in the oven, in a clay pot. My grandmother loved me very much and took me to church with her. Then the church was destroyed, but my faith remained for the rest of my life."

After the 10th grade, Nadiya went to Ternopil at the invitation of her uncle. After graduating from a trade school in Berezhany, she quickly mastered accounting and went to work in Pidvolochysk at a large enterprise. It was there that she met her beloved husband Bohdan.

"I remember we were going to another village for a reassessment, which is two kilometers away. The weather was good, warm. He managed to charm me in one day. He seemed so calm and kind, I thought to myself: he will make some girl happy. I became that girl.

We dated for a year and got married in 1958. Neither my parents nor his knew about our decision. Later we told them everything. We lived together for 47 years.

It was scary when in 1968 he was taken to Czechoslovakia at night. It was the time of the Soviet invasion of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. I was very worried. But, fortunately, a year later he came back alive and well. We had two daughters. I buried one daughter a few years ago," Nadiya says with sadness in her voice.

"You can't get used to war"

I look around: my interlocutor's room is full of embroidered pillows, paintings, and icons. Nadiya tells me that she herself has completed a course in cutting and sewing. Then she ran a sewing class at the Caritas Ukraine charity organization for children in Kyiv.

When the full-scale invasion began, she joined the volunteer work. She sewed bedding for the displaced. She says she worked from morning to evening and sewed more than 100 sets in a few days.

"I am finding this war incredibly difficult to endure. As soon as the siren starts to sound, I immediately listen to the news. It can be very loud. We have a shelter in our building with a toilet, sink, and water. I have never been down there yet. However, I am constantly afraid of alerts and think that I need to hide.

People say you can get used to it, but I can't. I don't have any grandchildren, so I took in an IDP woman. I have someone to talk to, and she has a roof over her head. In the evenings I cross-stitch. This is my only joy in life now."

This text is a part of the special project Children of War, in which we tell the stories of Ukrainians who witnessed the Second World War or its aftermath as children and are now experiencing another tragedy in their old age.

This piece was created as part of a project funded by the German Federal Foreign Office to support Ukrainian independent journalism.

Author: Lesia Rodina

- Share: