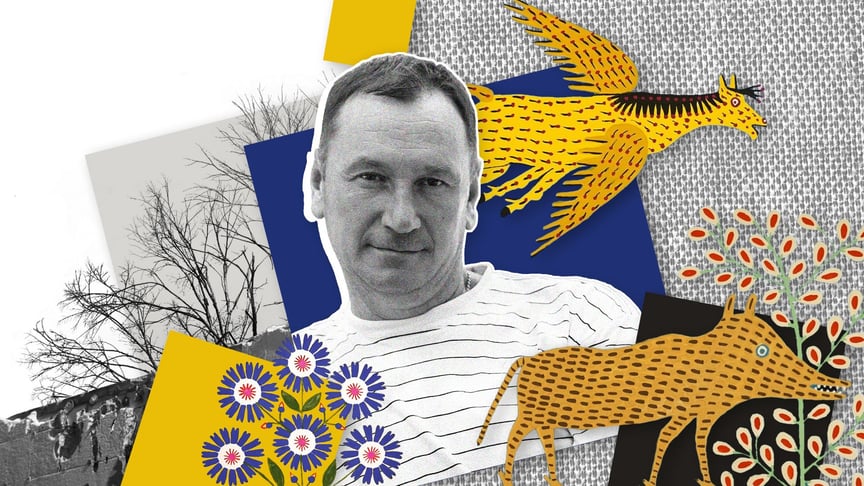

Savior of Prymachenko's paintings, "We didn't hide behind the fence to think later: I could have saved it, but I didn't"

Anatolii Kharytonov from Ivankiv is sick of journalists and their question: How did he save Maria Prymachenko's paintings from the burning local museum on February 25, 2022?

"I don't want to deal with reporters: you tell them one thing, and they twist your words. Then you feel ashamed in front of your friends, and people make fun of you. I'm already regretting that I agreed to meet with you," Anatolii tells me, barely having time to say hello.

"Don't act out, Anatolii. Right now, we will record the events as they really happened so that many years later, after reading our article, everyone will know the truth about the rescue of Prymachenko's paintings," I answer half-jokingly. "We want to talk about people faithfully fulfilling their professional duties during the war. You fulfilled your duty as a museum guard and saved the paintings, didn't you?"

"I didn't even think about the paintings; I planned to make horilka during those days."

"Did you succeed?"

"Yes, I did."

"You see, you managed to get everything done."

"Well, you won't write that I threw myself into the fire under shells, will you?"

"If you didn't do that, I won't write about it."

That was our conversation – a prologue to the rest of the story.

They were afraid of looters, not fire

It was very convenient for Anatolii to keep watch: the gate of the Kharytonovs' yard is five meters away from the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum building. He had worked at the museum for over 15 years, back in the days when there were no alarms or surveillance cameras. Anatolii has never seen a threat to the museum, except when young people gathered on the museum stairs to "have a good time." Only once during all the years of his job did Anatolii notice a window pane taken out of the window - perhaps someone was planning to rob the museum...

The work schedule was also convenient: two weeks on duty from eight in the evening to eight in the morning, and two weeks off. Anatolii "was having a rest" when he was on duty to Chornobyl.

"I handed over my shift to my partner, I think, on February 15 [2022]. On the 23rd, although I was on vacation, the museum director Halyna Korinna called me for help: she received an order from the management to collect the most valuable exhibits. We removed Prymachenko's paintings from the walls of the large hall and put them inside an oak kadub (a large barrel, ed.) for grain – this is also a museum exhibit, huge, up to two meters high, and it was in a small room, fenced off from the hall by a brick wall. No one knew what to do with these paintings. They were stored as they were: a canvas in frames behind glass, without being wrapped in anything, still we were afraid of looters, not fires," Anatolii says.

On February 24, 2022, Russian helicopters began flying over the house (so low that Anatolii could see the pilot's face), and the town was already being bombed. Anatolii did not receive any instructions from the museum management that day. He does not know if his partner, who was supposed to guard the museum that week, had any instructions. Anatolii's house is located on a hillside overlooking the Teteriv River – on February 25, in the morning, Russian armored vehicles had already crossed the river.

"There was a terrible roar, a battle on the bridge, a battle in the center of the town, shells were flying very densely over us, over the museum park. My wife and mother-in-law hid in the basement, and I stood at the entrance to the basement, making sure that the house was not hit," Anatolii says. "We were downstairs, and the museum was on a hill above us - it was hard to hear what hit the museum amid the roar. Then, somehow, everything quieted down. I went outside the gate and saw a piece of the museum's metal roof on the ground. I realized that the roof was hit. But the walls were intact, the glass in the windows was intact, so I calmed down. I thought that no looter could get through that hole from the shell."

"A godmother wouldn't send me into danger, but you're pushing me, you don't feel sorry for me"

A few minutes later, smoke poured from the roof. Kharytonov's job description obliged him to call "101" in case of a fire and to extinguish it if possible before the firefighters arrived.

"We started calling everywhere. There was a fight in the corner of the museum director's office. The head of the Ivankiv culture department said to try to put out the fire somehow. The firefighters, the police, and the state administration did not answer. We called so that no one would blame me later for not reporting to anyone, for entering the museum without orders. But I just made a decision."

The plastic was burning fiercely, the building was tall, it was impossible to get in through the hole in the roof without special equipment, the doors were locked, and the strong wind was fanning the fire. But they didn't even need a crowbar to break the bars out of the window: they easily came out of the foam plastic that covered the walls. Anatolii used the bars to break the window of the room where the barrel with the paintings was standing. The room was not yet on fire, the fire was just approaching, but the room was already filled with smoke...

"Tolia had no gloves, no helmet, no protection, no time to look for it all," says Natalia, Anatolii Kharytonov's wife. "I told him to get in quickly. And he jokes, saying, "My godmother wouldn't send me into danger, but you're pushing me, you don't feel sorry for me." I wasn't afraid when he was inside, I didn't have time to worry. But he could have suffocated, and anything could have happened because no one knew when the fire would reach the room, when the ceiling would fall."

Amazingly, Anatolii tilted that bulky barrel, took out the paintings, and handed them through the window, where his wife and mother-in-law were waiting, and then ran to their yard and put them on the blanket. Among the paintings were: Fairy Cockerel, Bull, Parrot Feeding Its Fish, Petryk Dragging Wheat, Hunchbacked Horse Flies Around the World and Arrives in Cities, and others. People came up from the ravine from the river side, and two more men, Ihor Nikolaienko and Maksym Cherednychenko, also climbed into the museum and began to help Anatolii.

"People saw us fussing, thought we were looting something from the museum, and started to come, about ten people arrived," Anatolii's mother-in-law, Nadiia Mykhailivna, recalls.

Occupiers behind the corner

They also wanted to save the paintings of other artists, precious towels of the folk artist Hanna Veres, but it was too late for Anatolii and his two assistants to get them. The fire reached the interior walls, twisted metal structures, and shredded plastic. "The museum burned to the ground in less than half an hour," Natalia says with sadness. The ceiling was sagging, about to fall on the guys, and the smoke was irritating their eyes. Meanwhile, Anatolii's partner who lived two streets away, and the head of the culture department, Nadiia Biriuk, arrived at the site.

"It was so hard: the museum was burning down before our eyes, and we were running around and failing to do anything to help," says Nadiia Biriuk.

Everyone was so nervous. Nadiia Biriuk begged that the fire be put out, but they shouted back that it was no use putting it out, saying it's better to thank God that the paintings were taken out and neither Prymachenko's works nor people suffered. At the same time, Russians were moving across the bridge over the river and through the neighboring streets, and fortunately, none of their vehicles turned into the museum. Neither a shell nor a bullet hit the museum.

"The head of the department insisted that Tolia take the paintings to his basement," says Kharytonov's mother-in-law, Nadiia Mykhailivna, "but we didn't want to. What if someone had killed us because of those paintings? Or we didn't save them? People would say that we were tempted by them, that we didn't give everything away. We felt at ease when those paintings were taken from the yard."

All the time, while people were trying to save at least something else from the museum besides Prymachenko's works, the paintings were lying in rows in the Kharytonovs' yard, no one was watching them: anyone could grab a painting and run away – no one would notice amid panic and confusion. But responsible people gathered near the museum ("self-reliant," as Anatolii said), and no one fell into sin.

...Nadiia Biriuk also did not want to take the paintings to her home, as her home in the village center was far away, and there were Russians around. So they decided to hide the paintings in the House of Culture, which is not far from the museum. Anatolii moved the exhibits to the House of Culture in his car, making a few trips. The works were kept there for the entire 36 days of the Russian occupation. It is a miracle that they were not destroyed by the attacks, and the occupiers did not come to loot it.

"When the museum already burned out, and it was possible to approach it, I took out what survived the fire," Anatolii says, "stone axes, jugs, ancient hoes, a plow, bronze busts of local World War II heroes so that looters wouldn't steal the bronze. Much of it was later taken to a museum in Kyiv. Later, we even pulled out a 1930s tractor with a crane, and now it stands in my yard so that no one can steal it."

"We do not pursue any rewards..."

Anatolii doesn't know where the paintings he rescued are now stored (he says, "No one reported to us"). He is only worried that someone tricky will not steal them. The last time Anatolii saw the paintings was last September at the Ukrainian House at the exhibition "Maria Prymachenko. Rescued" exhibition. Anatolii and Ihor Nikolaienko were fed up with the attention of journalists. Maria Prymachenko's great-granddaughter smiled at them, Minister of Culture Tkachenko shook their hands and called them saviors, and they even stood next to him on stage. Oleksii Kuleba, the then head of the Kyiv Regional Military Administration, said that Anatolii saved not just Prymachenko's paintings but the Ukrainian identity itself. He also shook Kharytonov's hand.

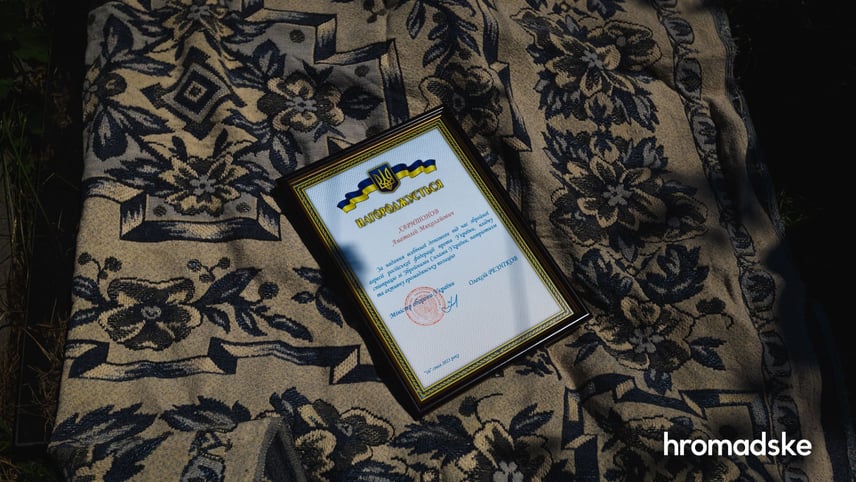

Last year, Nadiia Biriuk was awarded the title of Honored Worker of Culture of Ukraine for saving Ukrainian identity (though she says she has not yet been presented with the appropriate badge and certificate). And in January of this year, Anatolii Kharytonov received a framed diploma signed by Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov.

"At the Officers' House, I immediately saw those frames on the chairs and thought: that's for me," Anatolii laughs. "They were talking about me so much on TV that it was embarrassing. The people in the village were saying, "What did you, a fool, earn from this? You should have buried those paintings." But we didn't pursue any awards, we were saving our history. We did what we could. We didn't hide behind the fence to think now: I could have saved it but I didn't."

According to Nadiia Biriuk, the community submitted documents to award Anatolii with the Medal "For Labor and Victory" and the Order "For Courage" ("they redid the documents a hundred times") but ended up with a framed certificate.

Millions on the blanket

According to Nadiia Biriuk, last year's September exhibition of Prymachenko's paintings was organized in Kyiv to convince the public that the paintings were not missing. She says the rumors about their loss were spread on purpose so that during the occupation of Ivankiv, Russians would not look for the famous artist's works. After the exhibition, the paintings returned to Ivankiv. According to Nadiia Biriuk, only a few people know where they are kept now – in a safe place, at the proper temperature and humidity, everything is fine with them.

We can only hope that nothing bad will happen to the people who know the secret and that after the war, they can show where the paintings are stored, and that the uninsured masterpieces will survive the war. Nadiia Biriuk says no company in Ukraine wants to insure them because the responsibility scope is too big. Why not put the uninsured paintings in a special storage facility somewhere in Kyiv for the duration of the war? Especially since, according to Nadiia Biriuk, the Ministry of Culture offered to take the paintings to Kyiv for preservation and restoration.

"If you take these paintings to Kyiv, you won't find them," explains Nadiia Biriuk. "And is it safe in Kyiv? Kyiv has nothing to do with the paintings. Back in the early 1980s, the district department of culture bought them from Maria Oksentievna for 963 rubles. Currently, the paintings are communal property of the community, which is under the operational management of the Department of Culture, Tourism, Youth and Sports of the Ivankiv Village Council. As for the restoration, which costs a lot of money, it is reasonable to postpone this issue until the end of the war."

The up-to-date valuation of the paintings in Ivankiv was carried out after the de-occupation of the village. Hiring a professional valuer was too expensive, so employees conducted valuations on their own.

"We set up a valuation committee on the spot, consulted with museum directors, and came up with a price of about 8 million UAH for all 14 works," says Nadiia Biriuk. "At an auction last year, Prymachenko's painting Flowers Grew Near the Fourth Block was sold for $500,000. But this was an auction that raised money for the Armed Forces of Ukraine, so the paintings' prices were determined differently in that case."

... Anatolii, his wife, and mother-in-law know nothing about all these stories with paintings. They also do not know how many millions were lying on the blanket in their yard on February 25, 2022. But do they really need to know? Does money have a worth in the unearthly world of Prymachenko's paintings...

This text is part of hromadske special project dedicated to the Independence Day of Ukraine.

- Share: