Content

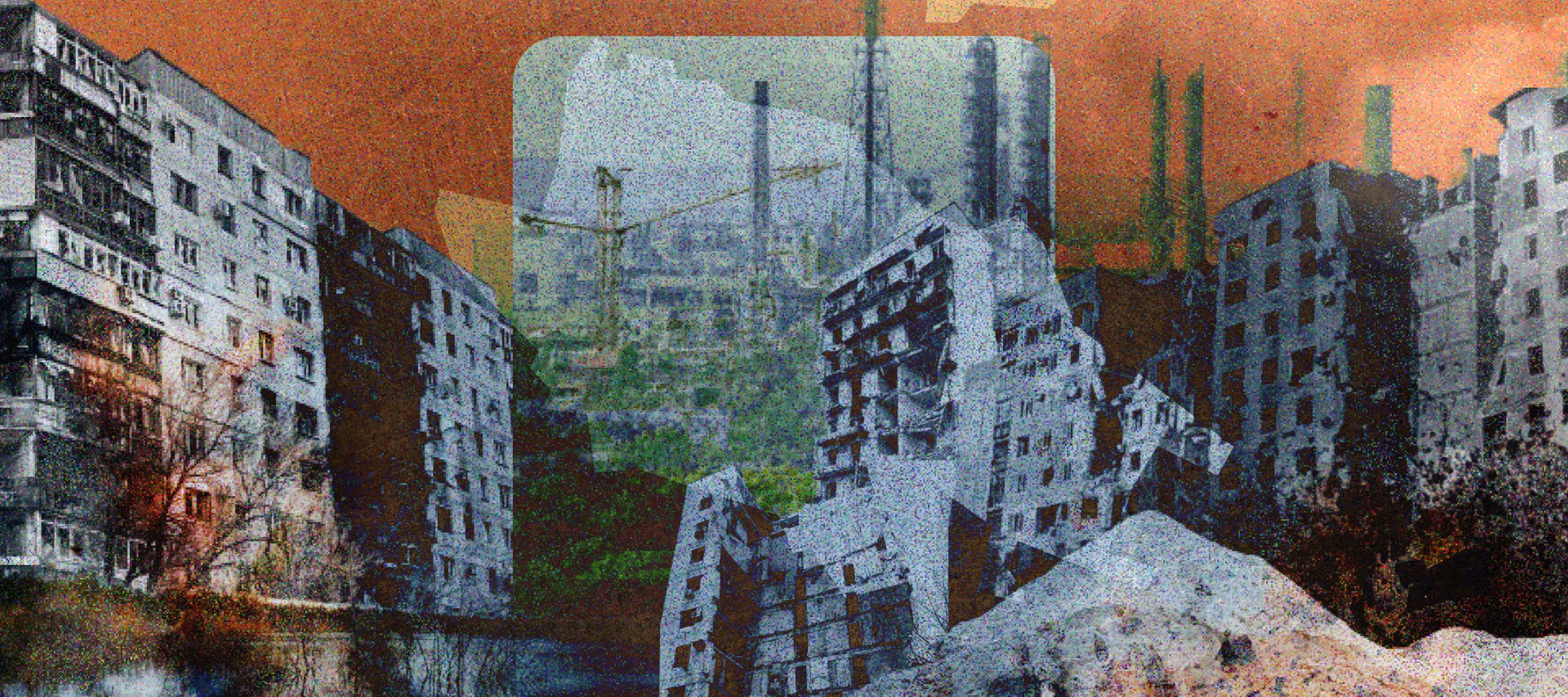

Siverskodonetsk: A city once reclaimed

hromadske

At first, Sievierodonetsk was just the neighboring buildings that Kyrylo saw through the window of his parents' apartment as a toddler. Over the years, the young man discovered new corners of his hometown: a courtyard with soccer goals painted on the wall of a transformer box; his grandparents' home on a quiet pedestrian street — those low-rise buildings were constructed by German prisoners of war after World War II, and Kyrylo loved their terraces and poplar shade; the "Mosaic" cafe with its marble floor, where ice cream of unforgettable taste was served in elegant bowls; the Ice Palace, where New Year's trees were set up; the Azot chemical plant, where he completed his internship as a technical school student; his family's store, where he worked...

Meanwhile, the city grew, seeking new opportunities for development. Until March 2022, when its outskirts ran into the line of defense.

That's when Kyrylo became its defender.

"There was nothing romantic about fighting in Sievierodonetsk. It was war, and I am a soldier. I didn't care about defending my hometown specifically. I defended Stanytsia Luhanska in the same way in 2015. But it was horrifying to see Grads tearing apart Sievierodonetsk. I later perceived the shelling of Bakhmut much more calmly. But here, a shell would land in a place where I used to go before the war, where I did something. There's a difference in feelings," Kyrylo says.

On June 25, 2022, Sievierodonetsk was captured by the Russians. The city is now more than 70% destroyed.

The city around the Azot plant

Initially, a settlement with the Soviet-style name Lyskhimbud was established on the bank of the Siverskyi Donets River, opposite Lysychansk, in 1934. Houses, barracks, a school and a kindergarten huddled around structures that would later become a chemical plant. But at the beginning of World War II, 10 buildings of the newly constructed enterprise were dismantled and taken beyond the Urals, and the war scattered the residents of the settlement. However, in December 1943, after the territory was liberated from the Germans, the Soviet authorities decided to rebuild the chemical plant and thus revive Lyskhimbud.

In 1950, the village was granted the status of an urban-type settlement and renamed Sievierodonetsk. The following year, the chemical plant produced its first output. By 1958, it had become such a powerful enterprise that the urban-type settlement where its workers lived officially became a city.

Until 2022, the chemical plant was one of the largest producers of ammonia, nitrogen fertilizers, and other chemical products in Europe — known worldwide as the Azot Association.

"Every family in our city was connected to the chemical plant in one way or another. My grandfather worked there as a fitter, and my grandmother was a research associate at the Institute of Nitrogen Industry. My grandfather and I would go to the Khimik stadium, where our famous football team, also named Khimik, played. The same name was given to the hockey team. The largest cultural center in the city was also called Khimik. Mosaics that adorned the city's buildings often had chemical themes. Schoolchildren in Sievierodonetsk were obligatorily taken to the Azot museum — I remember being impressed by a huge pile of salt in one of the halls. After school, many enrolled in our chemical-mechanical technical school because the city lived thanks to the chemical industry. I also graduated from it," Kyrylo says.

...With the onset of the full-scale war, the Russians targeted the Azot plant — its workshops and warehouses with chemical substances. Meanwhile, hundreds of Sievierodonetsk residents sought refuge in the plant's bomb shelters...

The Ukrainian issue

As a child, Kyrylo spent most of his time with his paternal grandparents. His grandfather was a Ukrainian from a village in Luhansk Oblast, and his grandmother was a Russian from Volgograd. After 1991, his grandmother began studying Ukrainian, read Taras Shevchenko and Ivan Kotliarevsky. She said that since she now lived in independent Ukraine, she should know Ukrainian culture.

"I was born in 1991 and studied in a Ukrainian school; there were many of them in Sievierodonetsk. But the whole city was Russian-speaking. I remember that as a schoolboy, I heard Ukrainian from some boy and was very surprised. I even asked him why he spoke Ukrainian. He replied that he was from Lviv. Well, I thought, OK. But thanks to my grandfather and grandmother, I grew up in a pro-Ukrainian bubble. And later, all my friends and close circle were pro-Ukrainian," Kyrylo says.

Meanwhile, Sievierodonetsk was in silent opposition to its status as a Ukrainian city, becoming a breeding ground for the now-banned Party of Regions. In particular, in November 2004, the so-called All-Ukrainian Congress of MPs and local councilors was held in the Ice Palace of Sievierodonetsk — supporters of Viktor Yanukovych from 17 regions of Ukraine spoke out against the Orange Revolution. Two days earlier, on November 26, 2004, the Luhansk Oblast Council declared disobedience to the central authorities, stopped deductions to the state budget, created its own executive committee, and appealed for support to Russian President Vladimir Putin. Among other things, the congress decided to hold a referendum on December 12, 2004, in the Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts regarding the granting of autonomy to these regions within a federal Ukraine.

"I was a child, 13 years old, but I remember that in our class there were two of us whose families supported the Orange Revolution," Kyrylo recalls.

At that time, in 2004, the Prosecutor General's Office and the Security Service of Ukraine initiated criminal cases against the organizers of the congress in Sievierodonetsk. Ten years later, Russian flags flew over the building of the regional administration of the Security Service of Ukraine in Luhansk.

Those 10 years in Kyrylo's life were very eventful: he graduated from school and technical school, seriously pursued basketball, was accepted into the Luhansk National Agrarian University as a promising athlete and, after the death of his stepfather, began helping his mother in the family business.

Azot, after its near-death experience in the 1990s, began modernization, and foreign investors came to the enterprise. Kyrylo says that, for example, a large workshop where his grandfather once worked was replaced by a single high-tech apparatus. Sievierodonetsk took second place in Luhansk Oblast in the development of small businesses. The names of new restaurants sparked the imagination — "Deja Vu," "Chalet." A nightclub, a new cinema and even a bowling alley appeared.

The year 2004 seemed to have faded into oblivion. Until much more serious events began.

Under the flag of the "LPR"

"Few people in the city spoke openly about the seizure of Crimea by the Russians. I was playing hockey at the time — in our amateur team, there were men of different ages and professions. Everyone communicated actively, but Crimea was not discussed. However, the atmosphere was such that people who supported Ukraine found themselves in the minority. Saying that you were for Ukraine was somehow uncomfortable. And in the family, in my bubble, the Russian aggression was initially perceived as nonsense that would soon pass," Kyrylo shares.

It did not pass.

On March 1, 2014, a "Russian spring" rally was held in Sievierodonetsk, followed by another on March 6. Crowds under Russian tricolors chanted "Russia!" and speakers called for "unity with Moscow." In early April, participants of a pro-Ukrainian flash mob were beaten by "titushky" — hired thugs — brought into the city; the police did not intervene. They also did not prevent the "titushky" from holding a pro-Russian rally the same day.

On April 27, the mayor of Sievierodonetsk, Valentyn Kazakov, called for the non-recognition of the Kyiv authorities. In the following days, "titushky" and pro-Russian militants seized the city's prosecutor's office and demanded the disconnection of Ukrainian TV channels. On May 9, the red Soviet flag was raised over the city council. On May 11, Sievierodonetsk held an illegal referendum on the recognition of the so-called "LPR" authority.

"I also received an invitation to the referendum; I crumpled that piece of paper and threw it away. I didn't go anywhere. In general, at that time, I tried to leave home as little as possible — I would deliver goods to the store from the warehouse and that was it. Once, with my brother and a friend, I went to the lake for a walk; there was a shooting range, and near it, under the flag of the 'LPR,' some armed 'militiamen' were drinking with a woman. They started harassing us, and that drunk woman started shouting, 'Shoot him!' We barely escaped from them. The situation in Sievierodonetsk was strange: a curfew, some armed people, checkpoints, but you could freely leave the city to Kharkiv. My mother and I didn't think about going anywhere — we hoped that all this would end soon," Kyrylo says.

Ukrainian troops liberated Sievierodonetsk on July 22, 2014. Heavy armor was involved in the storming of the city. That day, not a single customer came to Kyrylo and his mother's grocery store. He recalls:

"I woke up to the house shaking from shelling. I saw our plane flying very low — I could make out the trident on it. My mother said not to go for supplies, and to stay at home. And I, believe it or not, fell asleep again. At noon, a neighbor said that the city was already under Ukrainian control. I didn't believe him. We went with him to see what was happening on the streets. The city was quiet and empty. Ukrainian soldiers stopped us, checked the car. Ukrainian flags were really flying. That same day, I drove bread, stew, and groats from our store to the guys in my van. And then everything returned to normal very quickly, and Sievierodonetsk became a Ukrainian city again."

Moreover, Sievierodonetsk became the administrative center of that part of Luhansk Oblast that remained under the control of the Ukrainian government. Many regional institutions moved to the city — even the philharmonic with a symphony orchestra and a theater. New parks and an open-air cinema appeared. But Kyrylo saw this new Sievierodonetsk only in photos or during vacations: in January 2015, he became a fighter in the "Luhansk-1" volunteer battalion and participated in combat special operations. From 2018, he served as a police officer in Zaporizhzhia. In 2021, he became a police officer in Sievierodonetsk.

Bells over the city

"Around February 21, a friend from France called me and said he wanted to come fishing. He asked if there was a threat of war. What war? I was seriously into basketball, the sports season was in full swing, and I wasn't thinking about any war. But the next day, I was called to work on alert — to the Main Directorate of the National Police of Luhansk Oblast. They said there might be a war. They issued us weapons — I had an assault rifle and a pistol — and ordered us not to leave the base territory. We slept in the basement, and I planned to go home in the morning. And suddenly, in the middle of the night, one of our colleagues woke us up and said that the Russians had shelled many Ukrainian cities," Kyrylo says about the start of the full-scale war in Sievierodonetsk.

In the morning, the police were told to focus on defending the main directorate and ... wait for further instructions. The police dug trenches in the flower beds in front of the directorate and prepared the institution for evacuation to Dnipro. Kyrylo spent one night in Dnipro. Then he and several dozen police officers who had combat experience during the ATO were sent to defend Sievierodonetsk.

"My friends and I were assigned to the 79th Brigade. Our group consisted of 12 people. We dug trenches on the outskirts of the city, on the side of Rubizhne. We had assault rifles, a few grenade launchers and a machine gun that jammed, so we didn't fire it. We asked the commanders what to do if a tank advanced on us. They said, 'Run, but first notify us,'" Kyrylo says.

He remembers how in those first days of the full-scale war, the bells in the Sievierodonetsk churches rang frantically. Those were the churches of the Moscow Patriarchate — there was only one Ukrainian church in the city, tucked away in some room...

The Russians intensively shelled the city — in the basement of Kyrylo's home, many relatives and acquaintances gathered; it seemed that the entire Sievierodonetsk had hidden in the basements.

From March to May

...The Russians advanced from the eastern side, into the new districts of the city, destroying high-rise buildings. They rained down rockets and shells like peas. Kyrylo kept an eye on where they were aiming: when he determined that a shell might hit his mother's place, he called her if there was a connection. And he asked the guys who were going to the city to visit her...

"After the start of the defense, I first entered Sievierodonetsk around March 12. It was the area of the stadium and the park. Broken glass everywhere, twisted poles, piles of electrical wires, everything torn up by Russian artillery. By that time, not a single store was operating in the city. Only the hospital and the military-civilian administration were still functioning. In our house, although it was slightly damaged by shrapnel, and in the garage, we organized a warehouse for humanitarian aid. Many humanitarian aid distribution points appeared in the city at that time. I remember how people came out of the basements to my car and asked what I had brought... The Russians tried to hit these very points," Kyrylo bitterly notes.

Because of the humanitarian aid warehouse in the house, Kyrylo's mother did not want to leave the city. She decided to do so at the end of April when the Russians had already occupied almost half of Sievierodonetsk, and many still free streets were mined, and roads were blocked by anti-tank barriers. Kyrylo mapped out a route through the city for his relatives with the help of guys who distributed humanitarian aid until the last moment and knew the safe road.

...When Kyrylo went to pick up his mother, he saw the completely destroyed city center:

"They destroyed the shopping center, the theater, my favorite Ice Palace — I used to go there for training, children's matinees, competitions. Only a few walls remained of it — it's amazing that the mosaic on them survived. And the avenue that connected my stadium with the Ice Palace was destroyed. Along it were all the cafes and cultural centers, sports schools; it was my favorite route in the city — only ruins remained. Combat positions were already among the buildings, and not far from my house too. I remember that people were sunbathing near the buildings — and a Grad shelling began, everything around shook, and people ran to the basements. A depressing sight..."

His mother drove her car behind her son's vehicle — that's how they drove through Sievierodonetsk and Lysychansk and exited onto the Dnipro highway.

"There was a roadblock there; I stopped. I said, 'Mom, here's a card with money, floor it all the way to Dnipro, don't stop anywhere. Only in Dnipro.' I watched as my mother's car, packed with stuff, drove away — she even took the dog with her... I already understood that this was the end, who knows when we would return home, who knows what would happen to our home. It was very sad," Kyrylo says; we are talking on the phone, and I hear him nervously lighting a cigarette...

In Sievierodonetsk at the end of April 2022, Kyrylo was most impressed by the doctors. He then delivered medicines to the hospital — he saw an empty combat position near the building. The fighters were hiding in the hospital basement because there had just been a heavy shelling. In the corridors, Kyrylo met a soldier who was scared out of his wits. And in the wards, without hiding in the basement, doctors calmly went about their business — without body armor, without helmets, without weapons. There was no connection, and they communicated with each other using radios. And immediately after a shelling, they rushed to some ward where there were wounded...

"The last time I was in Sievierodonetsk was at the end of May 2022. By then, I had already been transferred to Lysychansk. And in my city, we wanted to repair the car. And one of my fellow soldiers asked me to pick up things from his house. Mines, shelling, in some areas of the city there were already close combat engagements with small arms, and you were foolishly risking your life for some stuff. It's stressful. Although I did take that baby stroller that I was asked to get. But I didn't take my own belongings. In my father's house, a notebook remained, in which my grandfather's brother recorded the memories of fellow villagers about our family. I really regret that notebook — I wonder if I'll find it after the war," Kyrylo says.

In May 2022, instead of the city, he saw burned-out buildings, collapsed entry sections, a pile of burned-out cars, mountains of rubble, bricks, and rebar. Vehicles made their way through these ruins. According to Kyrylo, out of almost 130,000 residents of Sievierodonetsk, only about 10,000 remained in the city...

Personal note

"I would like to live in Sievierodonetsk after the war. I love my house, my garage, where I liked to tinker with some equipment, the river, the forest. Our house with my mother, according to my information, can still be repaired. But I saw Bakhmut, Klishchiyivka, Toretsk — if the price of such battles is the liberation of Sievierodonetsk, then nothing will remain in the city that I loved so much. Unless the Russians leave the city as a result of some political decision. Otherwise — where to return?" says Lieutenant of the Liut (‘Rage’) Brigade Kyrylo Tytarenko.

***

If after the Second World War it was possible to revive the chemical plant on the Siverskyi Donets River and repopulate the area, then maybe it will be possible after this war?

This piece is part of the "Destroyed but Unconquered" project, in which we tell the stories of cities completely destroyed and occupied by Russia during the full-scale invasion.